“Trafficking + cult” does not function as a descriptive category but as a dangerous signal of contamination.

by María Vardé

Article 4 of 4. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

There are words that, once uttered, no longer describe: they condemn. In the contemporary criminal field, few have the performative power of “trafficking.” As soon as that label enters the scene, the public imagination does not wait for proof: it completes the picture on its own. And if the word “cult” is added to “trafficking,” the operation becomes even faster: a prefabricated cultural script is activated—recruitment, mind control, subjugation—that transforms ordinary practices into ominous signs. What follows is rarely a conversation about facts; it is a dispute over the moral framework through which those facts will be read.

This series has observed, through different case files, how that architecture of suspicion is produced: first, an explanatory “ghost” that displaces empirical evidence; then, a concept of “vulnerability” so expanded that it begins to absorb everything—women, foreigners, people of limited means, or those experiencing family difficulties, etc. Within that scheme, religious difference functions as an accelerator: what in other contexts would be interpreted as choice, discipline, belonging, or seeking is here recoded as crime. And when judicial and media systems feed off each other, the accusation ceases to be a hypothesis to be proven and becomes an anticipatory social condemnation.

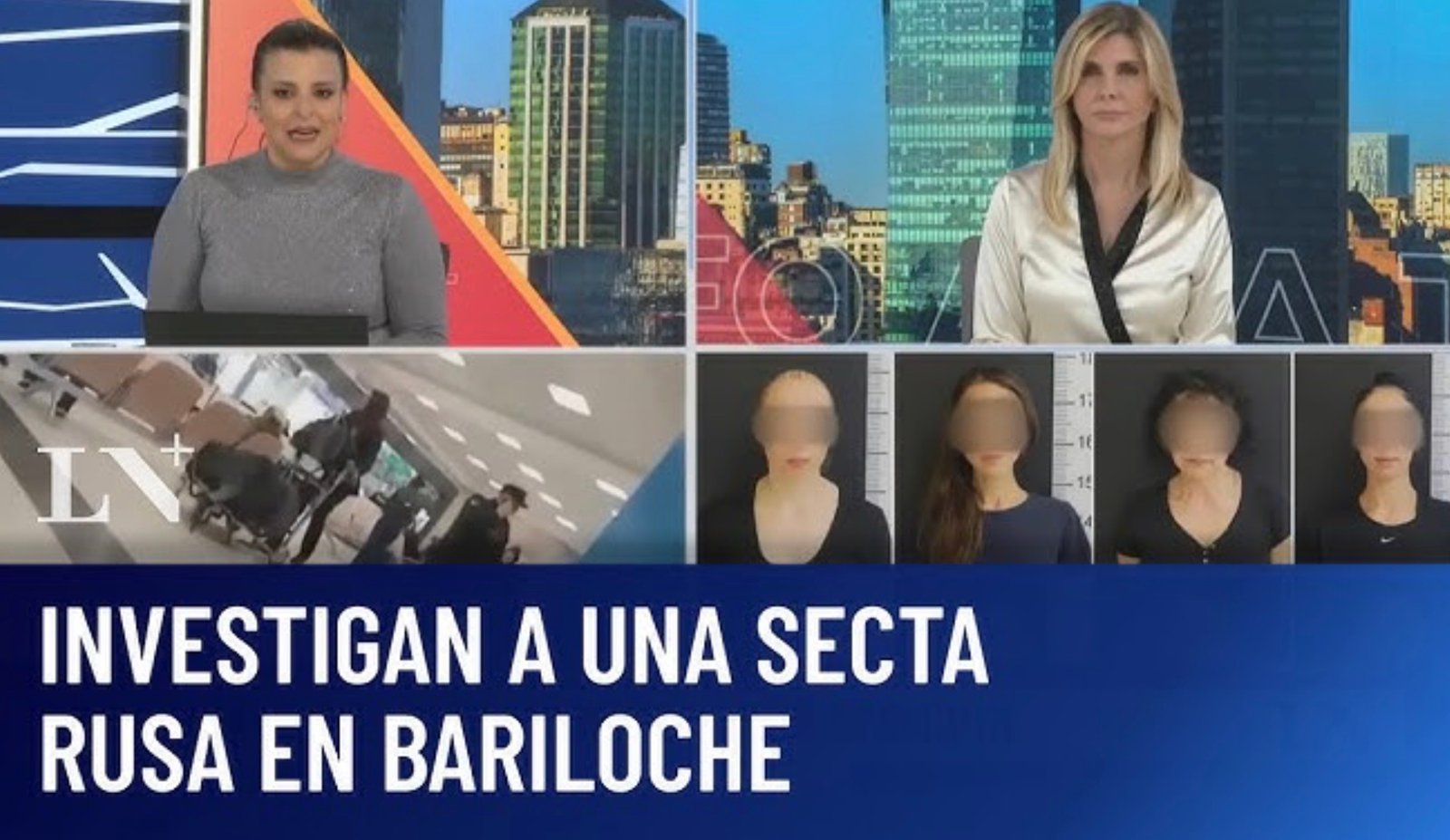

The Buenos Aires Yoga School (BAYS) case was spectacularized from moment zero: the national press was already positioned in front of the premises when the police began the searches and broadcast the transfer of all the accused detained on the night of August 12, 2022. Shortly thereafter, and for several months, photos, full names, and surnames of those involved were “leaked” to the media under the label “the cult of horror.”

Regarding Iglesia Tabernáculo Internacional, the Argentine newspaper “Clarín” stated: “‘It is God’s purpose,’ they told their victims. Under that pretext, the recruiters of a religious cult—dismantled in recent hours by the National Gendarmerie—targeted adolescents between 17 and 18 years old to exploit them for labor on a farm in the province of Entre Ríos.” The defendants were acquitted at trial.

In the case of Cómo Vivir por Fe, the media framing circulated forcefully, and, once again, the label “cult of horror” took on a life of its own, despite the case ultimately being archived.

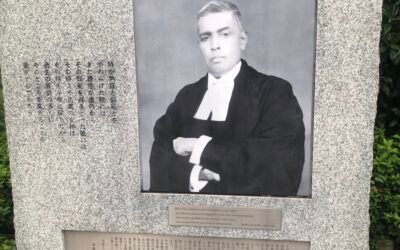

Continuing the tradition of headlines, Konstantin Rudnev was also labeled the leader of a “cult of horror.” On March 31, 2025—three days after his arrest—a headline in the newspaper “Infobae” read: “A cult from Montenegro, malnourished and hairless women, and a victim’s terror: the plot of the trafficking case uncovered in Bariloche.” In those days, images of Rudnev and of several of the women who had also been detained on that date circulated widely in the media. On April 8, 2025, the newspaper “Página 12” published: “Russian cult in Bariloche: 20 detainees released, except Konstantin Rudnev, the leader of the criminal organization.”

What does the media scene add to the architecture of suspicion? It adds speed and amplification. An accusation that, in a written submission, may be framed as a hypothesis becomes, in the newspaper, a closed story. And there is always the additional risk that a judge, perhaps without realizing it, will be carried along by that narrative: in the previous installment, part of a ruling was cited that reproduced verbatim, at the outset of the investigation, the popular discourse about “this type of organization” when he ordered the pretrial detention of Rudnev.

Spectacularization also fulfills a specific function: it makes the implausible plausible. If the public narrative has already installed the idea of a “transnational criminal organization” with “absolute control,” then any everyday detail can be presented as a clue.

From that moment on, anticipatory punishment is produced in several layers. The first is symbolic and social: ruptures in relationships, loss of employment, stigma, fear, and isolation. In the public sphere, “trafficking + cult” does not function as a descriptive category but as a signal of contamination. The question is not “what happened?” but “how could they?” And that question, in reality, already contains its answer.

The second layer is material: everyday life is profoundly altered, even if a court later concludes that there was no crime.

Up to this point, it might seem that the problem is the label “cult.” In fact, the problem is that the label is combined with a crime of extreme gravity. Trafficking enables severe penalties, exceptional logic, and a regime of suspicion justified by horror. There, the label “cult” yields a functional surplus: it sustains the idea that the accused can influence alleged victims even at a distance; that the word of someone who denies being a victim has no value because she would be “captured”; that the defense is part of the control; that any contradiction confirms the invisible harm. The result, in many cases, ends up being prolonged pretrial detention (a point illustrated by the more than three years Pastor Roberto Tagliabué spent in pretrial detention), with the consequent damage to health and reputation.

In a recent article, the case of Carlos Barragán—one of the suspects in the BAYS case, affected by a chronic illness that required sustained treatment—was documented; his detention led to severe deterioration and an open-heart operation. As with Tagliabué, the evidence ultimately favored his innocence, and he was dismissed. But the damage was already irreversible.

Konstantin Rudnev, still in pretrial detention, presents a very delicate health condition and a constant and significant loss of weight (more than 50 kilograms), according to the clinical references incorporated into the case file. The request for house arrest has already been denied twice because he could influence the victim. What is not assessed is that she is in Russia and, for ten months, has been making statements and filing complaints against prosecutors and other judicial operators for abuse of authority, insisting that she never knew Rudnev nor was his victim. She even created a blog to disseminate her story and seek justice, in her own words.

The case files show frictions that should halt the machinery, not accelerate it. Here, a point emerges that goes beyond the anecdotal and touches the heart of the problem: what does the system do when the “victim” does not recognize herself as such? What we observe is that, in these cases, the response is often to replace her voice with a theory: if she denies it, it is because she cannot see her own situation.

In other words: denial becomes evidence. The rhetorical circle closes. Beyond what one may think about the procedural conflict, what is relevant for this article is the contrast: the precautionary discourse insists on protecting someone who explicitly rejects that script.

Sociology has shown for decades that “punishment” does not reside only in the sentence, but in the process itself: costs, cumulative strain, reputation, family, and health. And contemporary studies point to a troubling finding. After months or years of deprivation of liberty, the accused may be induced to plead guilty in exchange for shortening the period of confinement. Moreover, as we saw in the previous installment, so many everyday acts can be framed as human trafficking that the Public Prosecutor’s Office often maintains that some suspects may be considered victims. Such a formulation leaves these individuals with an additional way out: adopting a victimhood narrative and aligning with the prosecution’s theory to regain their freedom. In all these scenarios, the risk is the same: that the conflict is not resolved in accordance with the facts, but rather to reduce immediate harm.

That finding proves nothing by itself about a particular case. But it does illuminate a structural risk: when pretrial detention is combined with public shaming and moral stigma (“trafficking + cult”), the system creates an environment in which resisting becomes costlier every day, and in which accepting a deal or accommodating oneself to the dominant narrative may appear, for some detainees, as the only way to stop the immediate damage to their bodies.

The closing of this series leads to a rather uncomfortable reflection: if, to sustain the accusation, it is necessary to convert mundane practices into criminal indicia and to replace the voice of the alleged victim with unprovable theories that disqualify her, then the risk of fabrication is real. Not fabrication as a novelistic conspiracy, but as bureaucratic production: a chain of inferences that reinforce one another until the case file tells a closed story, immune to the facts that contradict it.

And here appears the final blow, the one that should matter even to those who would not sympathize with an accused person or with a minority group: the elasticity of the framing. If “trafficking” can absorb translation work in a hospital, sharing goods, communal life, social assistance, religious discipline, rehabilitation, living near the group, or helping with a move, then the problem is no longer a case. It is a cultural precedent: any community can be rewritten as criminal.

Closing this series does not mean calling for impunity or minimizing real crimes. On the contrary, it means defending the seriousness of trafficking by preventing it from being trivialized through expansion. It means bearing in mind that a system that needs “ghosts” to sustain hypotheses ultimately loses its evidentiary compass. And it means insisting on a simple, almost ancient, but today radical idea: when the press and the justice system fall in love with the same script, truth ceases to invite inquiry, and freedom ceases to be a right, becoming a prize that arrives—if it arrives—far too late.

Maria Vardé graduated in Anthropological Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires and is currently a researcher at the Instituto de Ciencias Antropológicas, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires (Institute of Anthropological Sciences, Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities, University of Buenos Aires). She has written and lectured on archeology, spirituality, and freedom of religion or belief.