Some who claim to have been members of a religion or movement, and privy to its secrets, are simply lying.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 5. Read article 1.

Hundreds of thousands of English-speaking Protestants have received or purchased at least one tract published by The Gospel Hour, a Christian conservative ministry founded by South Carolina Baptist preacher Oliver Boyce Greene (1915–1976). His four-page tracts were easy to read, and he claimed they converted 200,000 to his brand of Christianity.

One of the most famous Greene tracts, which went under different titles—“Ye Shall Know the Truth and the Truth Will Make You Free,” or “I Wish I Might Testify to Every Jehovah’s Witness on Earth—What I Have Experienced Since I Became a Christian”—was signed by one Ollie Bell Pollard (1909–1984). It told the dramatic story of the apostasy of a Jehovah’s Witness who attended out of curiosity one of the Greene revival meetings, impressed by the fact that after the tent where it was taking place was hit by a cyclone the undaunted evangelist decided to carry on.

Pollard was also impressed, and a little bit scared, by Greene’s fiery sermon describing the flames of Hell, and came to realize that Jehovah’s Witnesses were outside of the true Protestant faith and will end up in Hell. Pollard reported that “I was convinced that the teachings of the Jehovah’s Witnesses were error and not the Truth that makes men free. I wanted the Truth and I was convinced the evangelist was telling the truth and proving it from the Bible.”

There is only one problem with this account. Pollard was never one of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. We can perhaps charitably assume some interest for the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ publications, but this is not the same as being baptized or being a member of the organization, which Pollard was not.

There is no reason to single out Greene for spreading false testimony. Revival preachers (and journalists) are so enthused by apostate stories that they do not always pause to check out whether they are true. This is not something new, and led to media scandals already in the 19th century.

Rebecca Reed (1813–1860) was a real apostate from Protestantism who converted to Catholicism at age 19, and spent a few months in an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts, as a novice. She then wrote Six Months in a Convent, where she claimed that she had been held against her will and tortured to persuade her to become a Catholic (in fact, she had converted before entering the convent). Her tales were so inflammatory that a mob assaulted the convent in 1834 and burned it to the ground. The nuns managed to escape, but the mob desecrated the graves and the bodies of the deceased religious buried near the convent.

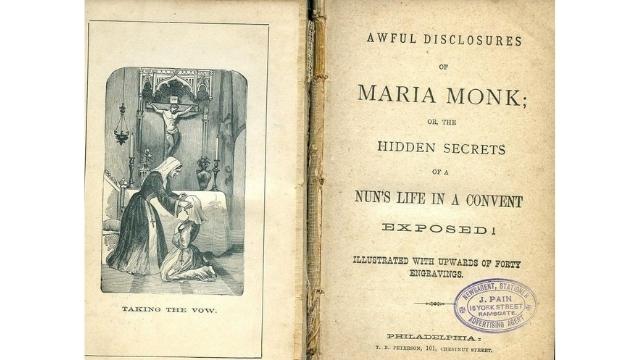

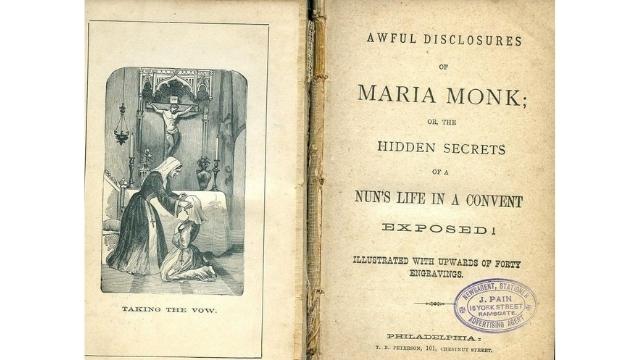

Reed inspired Maria Monk’s (1816–1849) 1836 book Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, or, The Hidden Secrets of a Nun’s Life in a Convent Exposed. Monk introduced herself as having been forcibly taken to a convent in Montreal to become a nun. There, she claimed, nuns were routinely raped by priests and, if they became pregnant, their children were aborted or murdered after birth. Luckily, she said, she escaped with her infant child to become a Protestant anti-Catholic crusader. Again, convents were assaulted in Canada by mobs who had read Monk’s best seller, until it came out she had never been a nun or novice in a convent, and the only facility she had escaped from was a psychiatric hospital.

What is interesting here is that accounts such as Reed’s and Monk’s were believed by respectable Protestant religionists and mainline media. Catholics denounced them, yet they were ready to believe similar, and equally false, accounts by women (men were much rarer) who wrote lurid stories of kidnapping and sexual abuse by the Mormons. The latter stories were so widely believed that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) created the character of Sherlock Holmes in 1877 for a story, A Study in Scarlet, featuring a girl kidnapped and forcibly married to a Utah Mormon elder, which he based on contemporary apostate accounts.

Media have continued to fall for false apostates, apologize when the hoaxes were discovered, and fall again. In the 20th century, Alberto Rivera (1935–1997) became famous as a Catholic priest who had apostatized, become a Protestant activist, and told horrific tales of priests raping nuns and killing the children they had conceived, some of them taken directly from Maria Monk’s book. Protestant publisher Jack Chick (1924–2016), whom I managed to interview in 1990, made Rivera’s books into widely distributed comics. To their credit, Evangelical reporters proved that Rivera had never been a Catholic priest and had spent the years when he allegedly served as a Jesuit in jail for fraud and credit card theft.

I was myself instrumental in exposing William Schnoebelen, a professional apostate who first misled the Mormons into believing he was a former Roman Catholic priest (he wasn’t) who had converted to the Latter-day Saint faith. He then became popular in the conservative Protestant circuit by claiming that he had been a high-level Mormon who had discovered that Mormons worshiped Satan in their temples. Later, he capitalized on all fashions among Evangelicals by claiming that he had apostatized from many different faiths. He claimed to be an ex-Freemason, ex-witch, ex-Satanist, and even, when vampire novels became popular, an ex-vampire. He offered no believable evidence of any of these claims.

False apostate ex-Satanists have plagued the media eager for stories about Satanism, with scandals erupting when some of the most famous, such as Mike Warnke in 1992, were exposed as frauds who had never been Satanists.

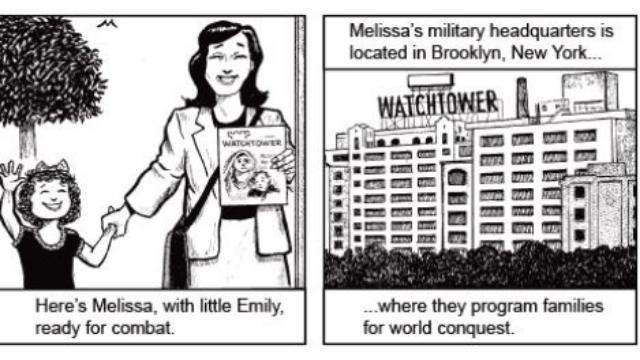

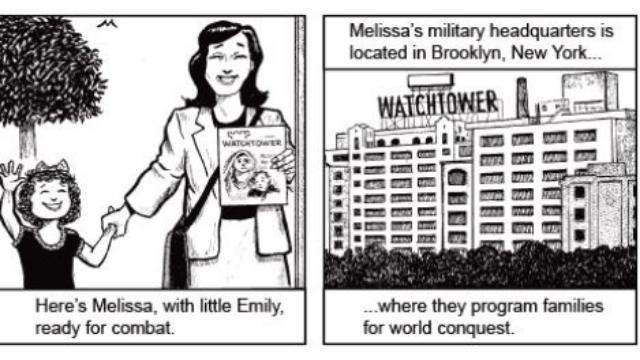

Jehovah’s Witnesses are a frequent target of anti-cult propaganda, and it is not surprising that false apostates from their organization have appeared, too. When I interviewed Jack Chick, he claimed to be in touch with one Melissa Gordon, who he claimed had gone through military-style training at what were then the Brooklyn headquarters of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, before converting to evangelical Christianity. In fact, Chick was never able to produce Melissa Gordon in person, although she was depicted in his comics, and she was probably just a figment of his fertile imagination.

When Dr. Gordon Eugene Duggar (1930–2014) passed away in 2014, obituaries celebrated him as a leading podiatrist in Georgia. I have no reason to doubt his qualifications in this field, but some more to doubt the apostasy story he penned with the cooperation of his wife Vera (née Poindexter, 1930–2019)—unless it was ghost-written—and published in 1985 as Jehovah’s Witnesses: Watch Out for the Watchtower! The publisher, the well-known Evangelical house Baker Publishing Group, advertised the doctor and his wife as “former Jehovah’s Witnesses.” Scholars who later researched the issue, however, concluded they were “on the periphery” of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, attended some meetings, but were never baptized.

Such inaccuracies, not to mention clear hoaxes and frauds, are so frequent, that media should handle reports proposed to them as apostate accounts with great care. But, as we will see, they don’t.