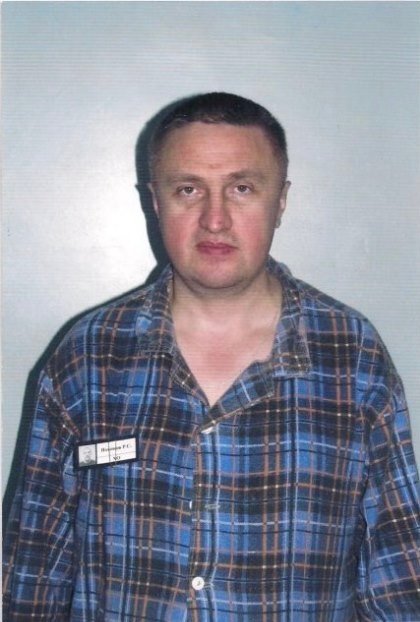

In 2013, Rudnev was sentenced in Novosibirsk and had to serve eleven years in prison. Many doubts remain about the trial’s fairness.

by Massimo Introvigne and María Vardé

Article 3 of 4. Read article 1 and article 2.

When the Novosibirsk District Court delivered its verdict against Konstantin Dmitrievich Rudnev on February 7, 2013, the courtroom atmosphere carried the unmistakable sense of a conclusion long foregone.

The eleven-year sentence, handed down after a sprawling investigation and a trial marked by procedural irregularities, was presented as the inevitable outcome of a dangerous man finally brought to justice. Yet the documents that would later emerge—including transcripts, expert reports, and the testimony of Rudnev’s wife, Tamara Saburova—tell a different story, one in which the machinery of prosecution appears to have moved with a momentum that preceded, and in many ways eclipsed, the evidence itself. The case file reveals a pattern of procedural shortcuts, witness contamination, and narrative construction that raises questions not only about the verdict but about the integrity of the judicial process that produced it.

The trial did not begin with the presumption of innocence. It began with a decade-long media campaign that had already shaped public perception of Rudnev as a “cult” leader, a manipulator, and a threat to social order. According to the defense, this “information attack” was not incidental but instrumental, a pre-trial conditioning of the public sphere that made it easier for investigators to frame the case and for the court to accept the prosecution’s claims without rigorous scrutiny.

According to Saburova, the raid did not mark the beginning of the investigation but rather the moment when years of fruitless inquiry finally gave way to manufactured accusations. Rudnev had been under law‑enforcement surveillance since 1999, long before any formal accusations were brought against him. In 2008, operatives conducted a search of his home, yet found nothing incriminating. He was detained for two days and then released, as neither drugs nor any alleged “victims”—the very elements investigators expected to uncover— were found. What followed was an intensified campaign of scrutiny: from 2008 to 2010, authorities launched a two‑year investigation aimed at uncovering even the slightest compromising material. During this period, numerous witnesses were questioned and twenty volumes of case files were compiled.

Yet despite this exhaustive effort, nothing criminal emerged. The absence of incriminating evidence did not lead to the closure of the inquiry; instead, it prompted a shift in strategy. Investigators began to reconstruct allegations, piecing together claims that could not be substantiated through direct proof. Moving from investigation to accusation-building marked a turning point, suggesting that the objective was no longer to determine whether a crime had occurred but to ensure that Rudnev could be charged with one.

One of the earliest tactics involved locating parents whose adult children had left home and attributing their departure to Rudnev’s supposed “brainwashing.” These parents claimed that his teachings had “pushed” their children to seek independence. Yet the adult children themselves testified clearly that their decisions were rooted in longstanding family constraints and a desire to begin independent lives—decisions they insisted were their own. Their statements, which directly contradicted the parents’ accusations, were disregarded. The complaints of the parents, though legally insufficient to justify more than a minor administrative infraction, were nevertheless used as pressure instruments, a way to keep the investigation alive despite its lack of substantive findings. When these complaints failed to produce a criminal case of the scale investigators sought, Saburova says the authorities simply “escalated to the next level, ”abandoning the search for evidence in favor of constructing a narrative that could support more serious charges.

According to Saburova the 2010 raid that led to Rudnev’s arrest unfolded with the kind of force usually reserved for counterterrorism operations. This is typical of raids against “cults,” not only in Russia, studied by scholars such as Susan Palmer and Stuart Wright. They do not serve any meaningful police purpose but are a sort of baroque theater staged for the media and reinforcing the anti-cult narrative. Saburova recalls being jolted awake at five in the morning as dozens of masked OMON officers armed with automatic weapons stormed the house, forcing everyone to the floor and herding them into a single room while pointing rifles directly at them. The atmosphere, she says, was one of orchestrated intimidation, a display of overwhelming power designed to shock and disorient. Rudnev was taken to another room, out of sight, where she believes officers planted the narcotics that would later form the basis of one of the most serious charges against him. From there he was transferred to a pre‑trial detention center, the first step in a process that, in her account, bore the unmistakable signs of pre‑engineered prosecution rather than a legitimate criminal investigation.

During the trial, ninety percent of witnesses admitted that their knowledge of Rudnev came not from personal experience but from television programs and unofficial websites. This admission, which in many jurisdictions would have triggered concerns about witness reliability, was noted but not acted upon by the court. The judge allowed testimony shaped by media narratives to stand alongside, and in some cases to outweigh, the absence of direct evidence.

The political context surrounding the case adds another layer of complexity. Rudnev had been an outspoken critic of the Russian government’s military ambitions, warning as early as 1999 that the country’s leadership would lead Russia into devastating conflicts with its neighbors. These warnings, which the wife frames as the true motive for his persecution, positioned him as a dissident voice at a time when independent spiritual movements were increasingly viewed with suspicion. She argues that Rudnev’s arrest and prosecution were not responses to criminal behavior but to political dissent, and that the charges served as a convenient vehicle for neutralizing a figure who challenged the state’s ideological narrative.

Central to the prosecution’s case was the assertion that Rudnev founded a “cult” known as “Ashram Shambala” in 1989. The defense counters that this organization did not exist during the period in question. Instead, Rudnev was involved in legally registered public associations such as the Siberian Association of Yogis and the Olirna Association, both of which operated openly and within the law. Their activities—yoga seminars, the sale of literature, music—were consistent with their stated purposes. The prosecution’s attempt to retroactively reinterpret these associations as the embryonic stages of a criminal “cult” required a leap of logic unsupported by the case file. There was no evidence that Rudnev selected, authorized, or financed the “unidentified persons” the prosecution claimed were his regional lieutenants. Nor was there proof of a centralized financial base. The court effectively transformed Rudnev’s past as a yoga teacher into the foundation of a clandestine “cult.” This transformation reflects what the defense describes as narrative retrofitting—the construction of a storyline that aligns with the prosecution’s theory even when the underlying facts do not.

Rudnev claims that, while formal organizations existed prior to 1999 and were later shut down, he continued to give public lectures until his arrest in 2010. After 1999, his activity shifted noticeably. Rather than focusing on organizational work, he increasingly positioned himself as a critic of the Putin regime, speaking openly about state manipulation and the mechanisms of control exercised by the authorities.

The sexual-crime charges represent perhaps the most troubling aspect of the case. These accusations rested almost entirely on the testimony of a single woman, A.V., whose statements the defense describes as contradictory and inconsistent. There is no independent evidence that A.V. knew Rudnev or had sexual relations with him.

The prosecution’s case hinged on the assertion that Rudnev took advantage of A.V.’s “helpless state,” yet the Supreme Court of Russia defines such a state as one in which the victim cannot understand the nature of the actions due to mental disorder, physical disability, or age. Experts initially found that A.V. was psychologically adequate, suffered from no mental abnormalities, and was fully aware of her actions during the period in question. The defense argues that the investigators effectively instructed another set of medical experts to confirm A.V.’s “helpless state” before they had even examined her, a violation of forensic neutrality that should have invalidated the expert opinion.

Even the timing of the accusation raises questions. The report of the crime was faxed from Kazan at a time when A.V.’s formal statement had not yet been accepted, suggesting a coordinated action rather than a spontaneous report. Throughout the investigation, Rudnev maintained that he had no sexual relationship with A.V. and did not even remember her. A hidden video recording of Rudnev speaking privately with a law enforcement official confirmed his consistent denial of the charges, yet the court refused to consider this recording as evidence of innocence. The defense argues that the sexual charges were not only unproven but deliberately constructed to inflame public opinion and justify the harshest possible sentence.

The narcotics charge, too, bears the hallmarks of fabrication. During the raid in September 2010, police claimed to find five grams of a narcotic substance in Rudnev’s home. Yet medical examinations of his blood, urine, and hair revealed no traces of drug use, despite the fact that hair retains evidence of consumption for months or even years. There was no evidence than any of Rudnev’s co-workers had been using drugs either.

The procedural violations during the search were extensive. The search protocol did not list all participants and lacked the signatures of several key officers. Rudnev was denied the opportunity to sign the protocol or express his position. The evidence bag was not stamped, underscoring chain-of-custody defects and the possibility of substitution. No drug paraphernalia—no scales, no packaging materials—was found in the house. The search protocol did not even record the use of a service dog; according to the defense, a trained dog reportedly conducted a search of the premises and found nothing. Despite the absence of buyers, contacts, or witnesses to any trafficking, the court sentenced Rudnev to eight years for this single episode, basing its conclusion on irrelevant testimony about events from 2005 and 2008. The defense argues that the narcotics charge was a classic example of evidence planting, designed to ensure a lengthy sentence even if other charges collapsed.

The financial narrative constructed by the prosecution played a significant role in shaping the court’s perception of Rudnev. Prosecutors argued that he enriched himself through the exploitation of followers, pointing to his ownership of cottages and luxury cars as evidence of illicit profit. Yet the defense presented documentation showing that Rudnev had inherited $400,000 from his grandfather in Germany, a fact corroborated by multiple witnesses. This inheritance fully accounted for his financial independence. The court, however, dismissed this explanation without substantive analysis, preferring a narrative that aligned with its broader portrayal of Rudnev as a manipulative “cult” leader. This selective treatment of evidence reflects what legal scholars might describe as confirmation-driven adjudication, in which the court privileges information that supports a predetermined conclusion while disregarding contradictory data.

The treatment of Rudnev’s book, “The Way of a Fool,” further illustrates this pattern. The prosecution labeled the text as extremist “cultic” doctrine, arguing that it promoted harmful ideas and manipulated vulnerable individuals. Yet, an expert analysis by the Institute of Criminalistics of the FSB found no calls for extremism, terrorism, or the severance of family ties. The court nevertheless used the book as evidence of ideological manipulation, conflating Rudnev’s past activities with current events to create the illusion of a continuous criminal enterprise. This approach suggests a narrative conflation strategy, in which disparate elements are woven together to support a cohesive but unsubstantiated storyline.

Throughout the trial, the court’s procedural conduct raised concerns about impartiality. Defense motions to declare evidence inadmissible were routinely rejected, while every request from the prosecution was granted. Some defense motions were left unaddressed for months, violating Rudnev’s right to a fair and timely defense. The court also failed to terminate the case regarding Article 239—creating a harmful association—despite the expiration of the statute of limitations. The use of “classified” witnesses whose testimony could not be objectively verified further undermined the fairness of the proceedings. These witnesses, whose identities were concealed, provided statements that aligned closely with the prosecution’s narrative but could not be cross-examined or scrutinized for credibility. The reliance on such testimony reflects a broader pattern of procedural opacity, in which the mechanisms of justice are obscured from both the defense and the public.

The court’s handling of expert testimony further illustrates the unevenness of the process. The defense presented multiple expert analyses—including psychiatric evaluations, forensic reports, and financial documentation—that contradicted key elements of the prosecution’s case. Yet the court consistently favored the prosecution’s experts, even when their conclusions were based on incomplete or questionable methodologies.

The cumulative effect of these procedural irregularities is difficult to ignore. The court’s consistent alignment with the prosecution, its dismissal of exculpatory evidence, and its reliance on questionable testimony and expert reports suggest a judicial process that prioritized conviction over truth. This pattern is not unique to Rudnev’s case; it reflects broader concerns about the independence of the judiciary in politically sensitive or “cult” cases in Russia. Yet the specifics of this trial—the media campaign, the political context, the fabrication of evidence—make it a particularly stark example of institutional bias.

The Rudnev case raises questions about the independence of the Russian judiciary, the role of the media in shaping public perception, and the vulnerability of individuals who challenge the state’s ideological narrative. To his family and followers, the trial appeared as a scripted performance designed to justify the silencing of a spiritual and political dissident. The appeal, though denied, stands as a record of these failures, documenting a case in which evidence was replaced by media-driven assumptions and procedural law was bent to suit a predetermined guilty verdict.

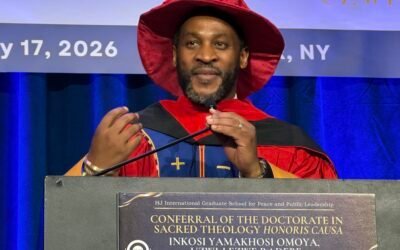

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.