Our study of the Xinjiang Police Files reveals one of the strangest collections ever of crimes for which Uyghurs are detained.

by Kok Bayraq

Last year, The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation (VOC) released a bombshell report entitled “Xinjiang Police Files” based on leaked internal documents from China’s police network.

In the process of searching for information about my friends and relatives in this report for a year, one point caught my attention: the strangeness of the arrest reasons.

Humanity has witnessed many atrocities and inequalities in the political and legal fields, both on paper and in practice, but it has never witnessed crimes as strange as those listed in the files.

Here are some excerpts from the archive:

1. “Eli Jume, 28, reason for internment: Family members of those who are not allowed to leave the country…” Why would a country restrict someone from going abroad? Could it be because debts the person leaves behind her would cause problems, or because the person’s appearance or statements would reveal the country’s dirty secrets? I would say the latter reason is true. The logical translation of “families not allowed to travel abroad” is members of families that are victims of, witnesses to, or rebels against the Uyghur genocide. Another strange feature of this case is that Eli Jume was arrested even if he did not attempt to leave the country.

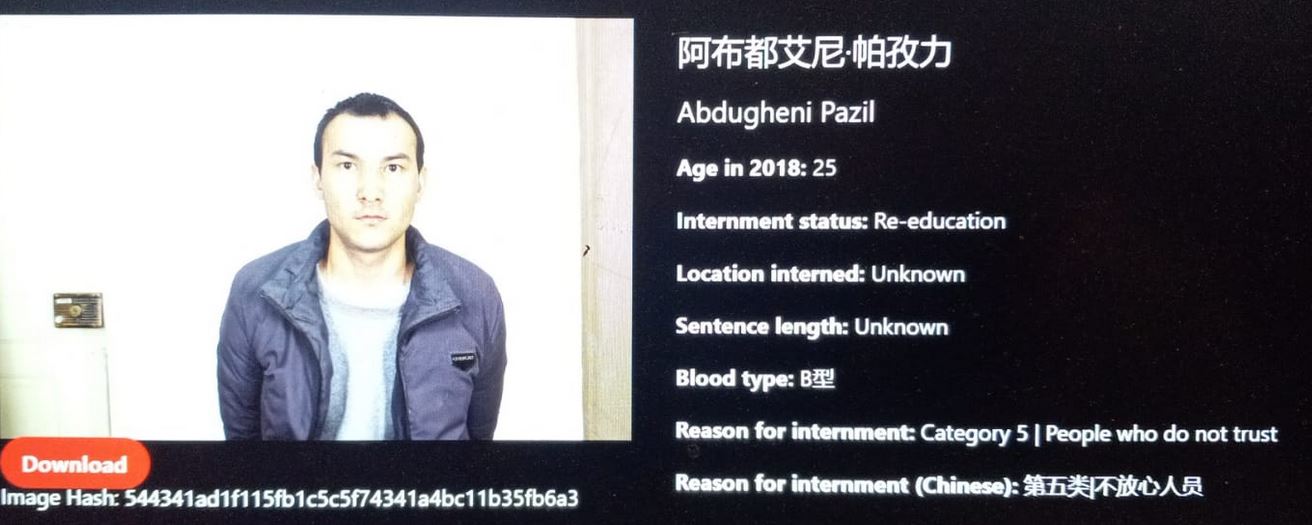

2. “Abdugheni Pazil , 25, reason for internment: People who don’t trust”.

What does “people who don’t trust” mean? There is no answer in the document.

However, there is a brief explanation in a report by Radio Free Asia for a similar case: “Those born in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s are [regarded as] dangerous generations.” A village security chief cited from instruction on his hand and continued: “They have not experienced famine and the political storms, like generations before them; and they are not much appreciative of Party and state, and are daring and brave at making turbulence in the society.” What is the term for a specific group being targeted for elimination? Genocide!

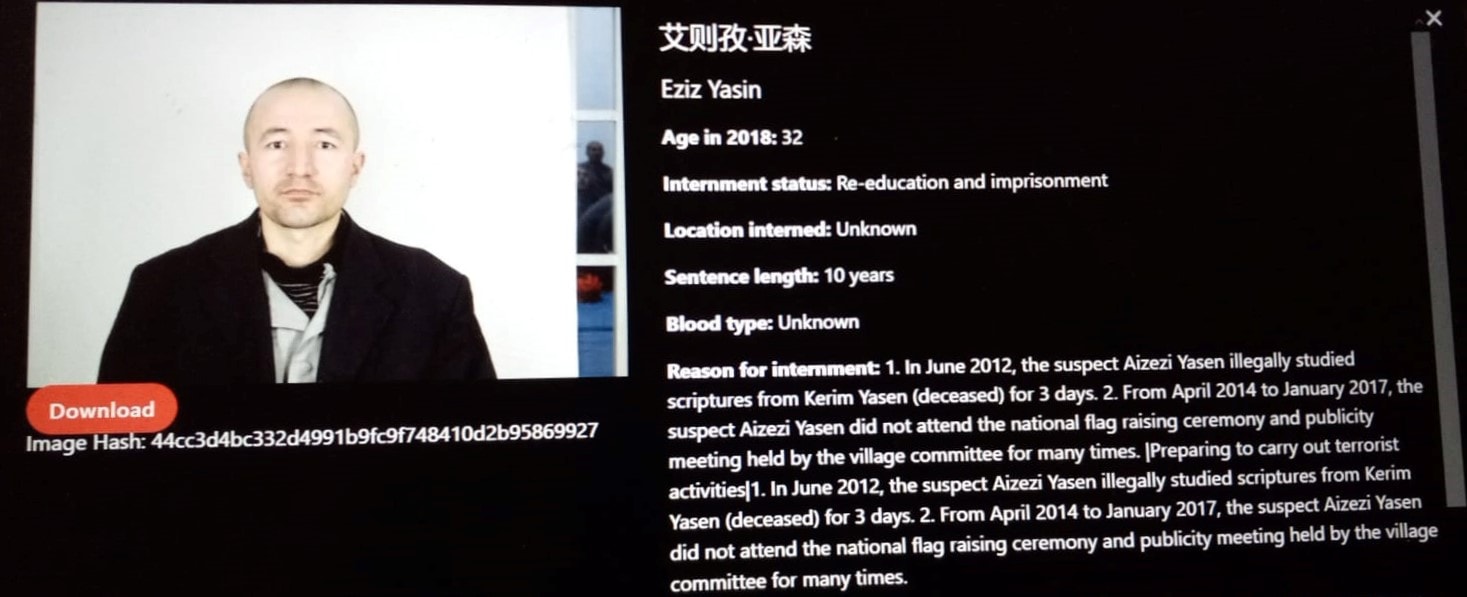

3. “Eziz Yasin, 32.” One of the reasons for internment: “In June 2012, the suspect Eziz Yasin illegally studied scriptures from Kerim Yasin (deceased [his brother]) for 3 days…” All those who are born and raised in a family belonging to a particular religion, whether Buddhist, Christian, or Muslim, normally take religious classes for at least a few days or a few hours throughout their lives.

The reason for internment shows that the aim is the eradication of religious identity, which is not tolerated. The same logic is confirmed in another official document stating that Islam is a mental illness and that a person who is affected by it must be “purified” and “treated.” What word should we use for the forcible eradication of a religious identity? “Forced assimilation”? Or something worse?

4. “Rabigul Abduweli, 31,” reason for internment: based on the rule that “everybody who needs to be arrested should be arrested.” This looks even more strange, the more so in a country that keeps telling the international community that it respects the “rule of law.” The subtext implies that all Uyghurs may be arrested just for being Uyghurs.

5. “Eziz Ibrahim, 33.” One of the reasons for internment: in 2012, when he got married, he didn’t play the piano at his marriage. There was a reason for this.

After the crackdown campaigns in the region, the local communities had lost many of their friends and relatives and were not able to organize funerals for them. Thus, they decided to stop singing and dancing for a while, including at their weddings, to pay their respects to their heroes. The fact that such consciousness emerged among the Uyghurs was considered a crime.

6. “Huseyin Memet, 51. One of the reasons for internment: he did not go funerals (nor to weddings). It was also reported that a villager was detained because he did not hold the ceremony of Nazir when his mother died, which raised suspects of religious extremism. In recent decades, some groups among the Uyghurs find it more virtuous to donate money to others than to hold the Nazir ceremony, and the Chinese authorities consider it a sign of “Wahhabism.” Thus, the situation evolved to a point when Uyghurs can only laugh and cry with the permission of the state.

The list goes on and on. We can list more than one hundred categories of such strange reasons for being detained, and thousands of detainees in each category.

Eziz Ibrahim and Huseyin Memet’s cases, where one was detained for not laughing and celebrating and another for not crying, mirror the following story.

There was a student who was a bully at his university, and he liked to “train” new students at the school. He entered the first-year-students dormitory and asked, “What did you have for lunch today?” “Dumplings” said a student. “Why didn’t you eat noodles?” the bully asked, slapping the student’s face. Then he turned to another student. “What did you have for lunch?” he asked again. The second student, who had learned from the experience of the first, answered “Noodles.”

The bully then asked, “Why didn’t you eat dumplings?” and slapped the second student as well.

The arrest reasons in the Chinese police documents are similar to the bully’s “educational” strategy. They make no sense. Clearly, the bully’s purpose was to show his strength. China’s goal is much more sinister—to wipe Uyghurs and their identity from the face of the earth.

In short, as demonstrated by the files, being a Uyghur is a crime. As a Uyghur, I am not surprised. What I’m wondering is how can China still be a member of the UN Human Rights Committee after such atrocities were revealed to the world? And how some countries can expect mediations for peace from China in international affairs such as the Ukraine war? What is missing: decency, intelligence, or the power to punish crimes against humanity?