He calls the Salvation Army a “coercive organization” and uses against “Bitter Winter” the same strategies anti-cultists attribute to “cults.”

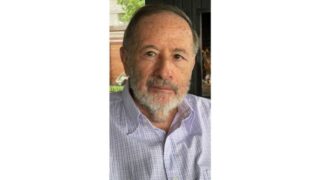

by Massimo Introvigne

In 1985, Swiss historian Jean-François Mayer wrote a short book on how in the 1880s the Salvation Army was slandered in Switzerland with arguments very similar to those used in the 20th century against “cults” (“Une honteuse exploitation des esprits et des porte-monnaies?”, Fribourg: Les Trois Nornes). Mayer even published a table showing how similar the two sets of accusations were.

The point he wanted to make is that just as today accusing the Salvation Army of being a “cult” would look ridiculous and absurd, perhaps in the future, when sober tempers will prevail, some parallel accusations against groups currently labeled as “cults” will also be dismissed.

One of my mentors, however, once told me that no matter how absurd a theory is, you will always find somebody crazy enough to revive it. Although Mayer could not have predicted it in 1985, in 2023 a bizarre Argentinian anti-cult activist, Pablo Salum, calls the Salvation Army a “coercive organization” and a “cult” (secta) in its shows against the “cults” on YouTube and Twitch.

This is not surprising, since Salum has referred to Falun Gong, with words that looked like he had borrowed them from the Chinese Communist Party propaganda, as “one of the most dangerous Chinese coercive organizations.” The Jehovah’s Witnesses were labeled a “coercive organization terrorist cult”; the Wicca a “cult and coercive organization”; the Latter-day Saints (popularly known as the Mormons) another “coercive organization cult,” whose leaders also “hide pedophiles.” Salum’s catalogue of “cults” has no ends, and includes Freemasonry, the Seventh-day Adventists, and even the Catholic Discalced Carmelite nuns.

He took advantage of the recent incident involving the Dalai Lama and a young boy to call His Holiness “this criminal who wants to be called Dalai Lama,” the Tibetan Buddhism he leads “a cult involved in human trafficking and pedophilia,” the Buddhist movement Soka Gakkai “a coercive criminal organization,” and Buddhism in general a religion hiding “obscure coercive doctrines” typical of “cults.” Frankly speaking, it would be difficult to find a religion that is “not” a “coercive organization” and a “cult” according to Salum.

Salum would not deserve special attention if he was not used by a special Argentinian prosecutorial agency called PROTEX to advance its own agenda of cracking down on religious and spiritual minorities through an abusive interpretation of the notion of “human trafficking” rooted in the pseudo-scientific theory of “brainwashing” or “coercive persuasion.”

Paradoxically, Salum adopts the same strategies anti-cultists regard as typical of “cults.” For decades, as documented by American scholar Andrew Ventimiglia in his “Copyrighting God: Ownership of the Sacred in American Religion” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), anti-cultists have vituperated against the Church of Scientology and other groups they label as “cults” for their use or abuse of copyright laws to prevent criticism. Scientology, in particular, has successfully shut down several anti-cult websites that, to criticize the church, used images and texts it had copyrighted.

While in the cases discussed by Ventimiglia I personally believe Scientology was right, as long texts and in some cases entire voluminous books were illegally reproduced, there are certainly other cases where copyright claims are used as a tool to shut down criticism. This is particularly easy on YouTube, where claims are mostly handled by computers rather than human beings. Computers prefer to err on the side of caution and accept almost all copyright claims at face value. YouTube itself admits that millions of false copyright claims are filed every year to harass legitimate users, some of whom are blackmailed and asked to pay money to end the harassment.

“Bitter Winter” illustrated some articles by Canadian scholar Susan Palmer and others about Salum’s and Protex’s abuses with videos prepared by members (not involved in the current court case), ex-members, and relatives of members of the Buenos Aires Yoga School (BAYS, a main target of these abuses). To explain who Salum was and document his contradictions, the videos included clips with his statements. In most countries of the world, this is recognized as “fair use” of copyrightable material. Anti-cultists constantly use my own image and clips from my speeches to criticize me, and I have never complained.

Salum, however, had learned enough about the real or imaginary tactics of the “cults” that he used them himself, and filed complaints with YouTube about the videos we had uploaded in our channel for easier access. We know, there are possible appeals and one can always sue in court, but we run a daily magazine with thousands of articles, know that they are mostly read in the first days after they are published, and have no time or resources to spend years fighting against ill-founded copyright infringement charges. The videos were uploaded to a platform other than YouTube and we provide again links to them.

On the other hand, although these are probably concepts too complicated for Salum, sometimes silence speaks loudly than speech, and an emptiness is more significant than a presence (a Buddhist concept, by the way, and no doubt for Salum one of its “obscure coercive doctrines”).

We believe that leaving a void where once the videos were, with the notice that they have been eliminated “due to a copyright claim by Pablo Salum” may explain even more eloquently than the videos themselves what kind of individual Salum is, and how anti-cultists are guilty of the same abuses they accuse “cults” of.