Prosecutors argue that whoever joins a spiritual group they do not approve of is “vulnerable.”

by María Vardé

Article 2 of 4. Read article 1.

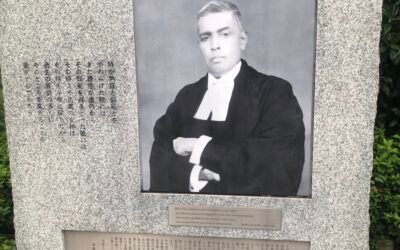

This series analyzes, through an anthropological-legal study of five high-profile cases, how judicial proceedings for human trafficking in Argentina intertwine with anti-cult campaigns in the discursive construction of suspicion. The first part described how the theory of “brainwashing”—long discredited by the scientific community—has been revived as a procedural dogma. This article focuses on the device that usually complements it: the notion of “vulnerability.”

Anthropologists such as Cecilia Varela and Jessica Gutiérrez have shown how judicial operators carry out an “interpretive labor” on conditions of vulnerability, expanding that notion to an excessively broad range. They point out that this discursive production subsequently functions as procedural input, as it is erected as evidence and replaces the voice of the alleged victims.

In the Rudnev case, the prosecution framed the alleged victim, E., as “vulnerable” due to her condition as a pregnant migrant. Then, during the hearing for the formalization of charges, it argued that it was “at least facing two victims in a clear situation of vulnerability.” It asserted that “the victim” had been trafficked by a “coercive organization” and maintained that “these types of criminal groups take advantage of people in situations of vulnerability,” for which reason “it cannot be ruled out that some of the indicted women are also victims.” These women (among them a physician, a translator, a master’s degree holder in social anthropology with studies in literature, a clinical psychologist, a web designer, a graduate in Economic Sciences specialized in marketing and international relations, a lawyer, and a systems analyst) were considered “vulnerable” in a generic and ambiguous manner, without specifying who or for what reason any of them could be considered as such.

The interventions and statements of E. sharply contrast with that institutional script. In her expansion of the complaint against the prosecutors, she described her decision to travel to Argentina to end a situation of domestic violence with her former partner and to begin a new life. She also stated that she maintained permanent contact with her family in Russia, a fact corroborated by her phone records. For E., that trip was an act of personal agency and a search for safety; however, the judicial system reclassified her life plans as the product of trafficking. Even after returning to Russia, E. has continued to intervene in the Argentine proceedings to clarify that the “macabre system” of state surveillance she endured since childbirth at the Ramón Carrillo Hospital in Bariloche was the only victimizing element.

The Buenos Aires Yoga School (BAYS) case presents a more detailed elaboration of the supposed “vulnerability” of the women identified as victims. In the record drawn up by professionals from the National Program for Rescue and Accompaniment (PNR) during the raids, with reference to one of those women, the following is stated: “From her account it is possible to infer that she was in a situation of extreme vulnerability at the time of entering the ‘school,’ since she felt—according to her own statements—that the people of the organization, without specifying who, had ‘helped’ her.” This discourse was incorporated verbatim by the prosecution in its request to elevate the case to trial, together with the DATIP report, which among other things states: “The interviewees in question share another significant aspect to consider: in their life history they place their entry into BAYS as a way of seeking answers to existential questions, understanding what they wanted to do with their lives and where to go, or finding meaning in difficult situations they had experienced. A state of ‘emotional vulnerability’ is evident, caused by multiple situations such as bereavements, family and work conflicts, and certain life crises. Both factors mentioned make these individuals more vulnerable to recruitment by cults and sects.”

As in E.’s case, the interventions of these women in the case file recount a different scenario. From the outset of the proceedings, they have submitted life narratives, professional degrees, photos of activities unrelated to BAYS, certificates of higher education, participation in international conferences, and certified statements from family members and acquaintances. They also initiated legal actions against the prosecutors, testified at hearings, and demanded that the judicial authorities cease to consider them victims. They maintain that their lives are fully autonomous, but the prosecutorial discourse prevailed over their self-perception (and their psychiatric evaluations). In an interview with the author, one of them emphasized: “The State assumes that because I sought another way of living, I lost my capacity to think; they treat my grief not as a human experience, but as a legal defect.”

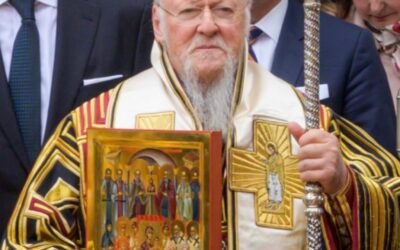

In the case of the Christian community Cómo Vivir por Fe (CVPF), the Office of the Prosecutor for Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons (PROTEX) argued that the alleged victim, Gabriela, was vulnerable due to an “extremely fragile emotional situation,” attributed to a recent separation and to her condition as a woman. This latter factor, according to PROTEX, represented a disadvantage due to her insertion “in a religious structure traditionally characterized by sexist beliefs and stereotypes about women,” which constituted “a concrete and objective factor of structural vulnerability.” With this assertion, PROTEX opened the door to considering every Christian woman “vulnerable.”

That narrative contrasted with Gabriela’s testimony before the court: her separation had occurred more than a year before she joined CVPF. Her incorporation into the community had been carefully considered, she had discussed it beforehand with her family, and it took place at a time when her emotional and economic situation was very stable.

In the case of the Tabernáculo Internacional Church, the court questioned the “vulnerability” of the alleged victims. In that regard, it emphasized: “all the testimonies heard were given by young people of different ages who demonstrated a highly eloquent capacity to account for their statements. Mostly with complete basic studies and at least with past or present university experience. And also capable of testifying with clear and forceful language (…) Certainly far removed from any symptom of vulnerability.” For the court, this contrasted deeply with the PNR reports and the prosecutorial accusations and demonstrated a clear lack of knowledge of the living conditions of the people they claimed to “rescue.”

Another notable judicial reaction to this phenomenon has found expression in the recent case of Pastor Roberto Tagliabué. In his ruling, Judge Roberto Falcone observed that the vulnerability of the alleged victims was not in dispute. However, he stated, “the vulnerability that the accusation invokes as an element of recruitment was, in reality, the starting point of a solidarity-based action that sought to help when no one else did,” referring to the assistance activities carried out by the pastor. He noted that the professional members of the PNR “resorted to general indicative factors of vulnerability as if their mere verification were sufficient to affirm the existence of a process of annihilation of self-determination by means of an altruistic religious discourse. Ultimately, their statements (…) do not constitute direct evidence of the alleged facts, but rather subjective assessments based on an isolated contact lacking continuity.” He criticized the prosecution for ignoring the testimony of the alleged victims and pointed out that these generic formulations arise from the lack of fieldwork by PNR professionals and prosecutors.

The cases analyzed confirm the broad universe encompassed by “vulnerability” for anti-trafficking bureaucracies which Argentine academic studies had already warned about. Ordinary biographical traits such as separations, family conflicts, or motherhood, as well as the mere fact of being a woman, open a range from which few people could escape.

They also show a drift with deeper consequences: its extension to religious traits, such as spiritual seeking or the search for existential answers. Moreover, gender-based critiques of religion can be reused as proof of “structural vulnerability” without demonstrating how those abstractions operated in the concrete relationships under investigation. Indeed, what is striking in these case files is the absence of detailed socio-environmental inquiries on a case-by-case basis: instead of field analyses of the environments, networks, and decision-making contexts of the alleged victims, the files rely on generalizations and bureaucratic templates. Within this framework, “vulnerability” ceases to describe a social condition and becomes a legal instrument used to replace the protagonists’ testimonies with a narrative aligned with the prosecutorial claim.

In practice, this state of affairs enables an informal—albeit state—regulation of religious heterodoxies, as it facilitates the translation of their activities and traits into criminal categories, which will be the subject of the next article. Once that script is installed in the case file, its circulation beyond the proceedings—leaks, headlines, moral panics—becomes almost automatic: suspicion is already structured, and the verdict ceases to be the moment when truth is decided.

Maria Vardé graduated in Anthropological Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires and is currently a researcher at the Instituto de Ciencias Antropológicas, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires (Institute of Anthropological Sciences, Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities, University of Buenos Aires). She has written and lectured on archeology, spirituality, and freedom of religion or belief.