The anti-cult journalist blames the victim for a message he sent to a Unification Church-related organization. He should instead blame himself for the hate he spread.

by Massimo Introvigne

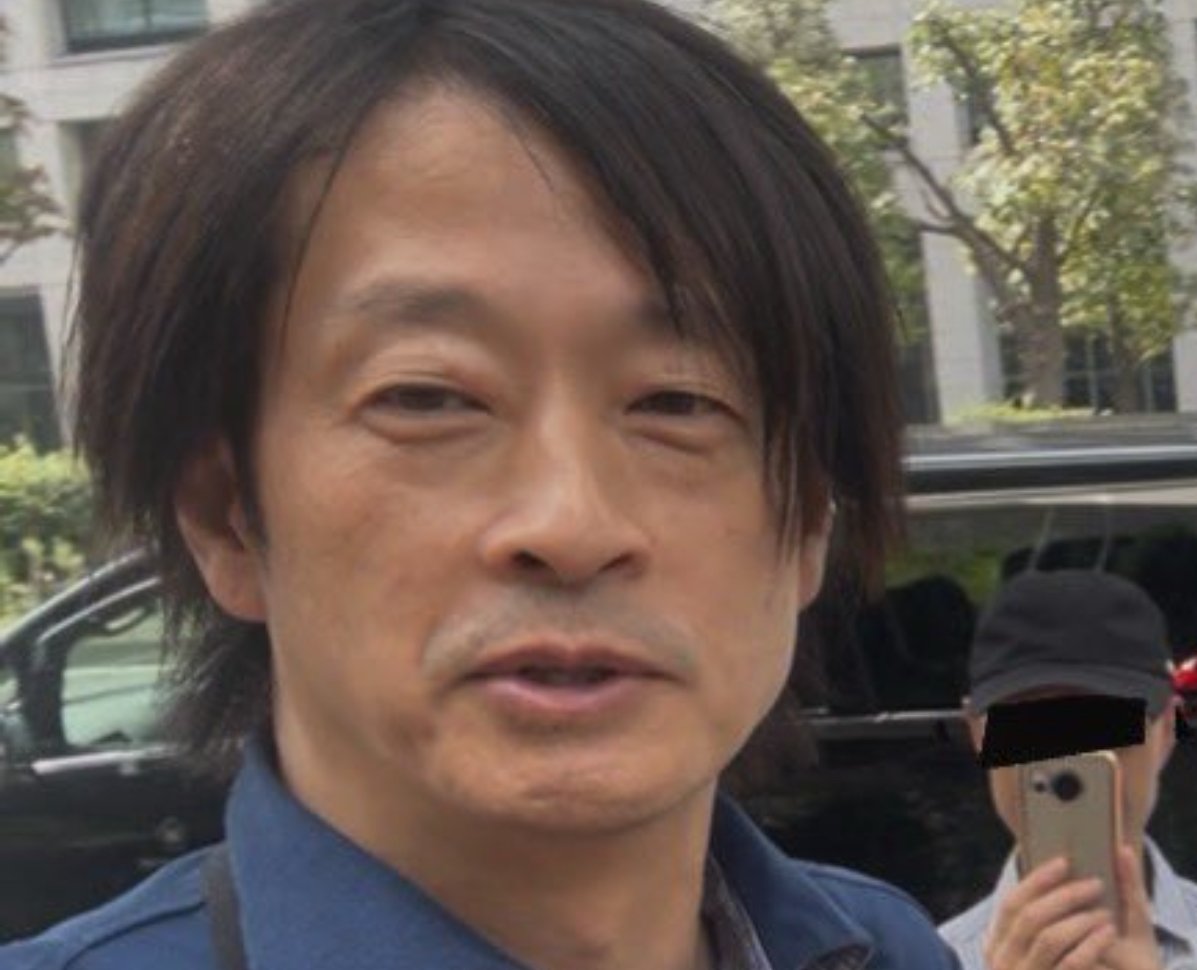

There are moments when journalism ceases to be reporting and becomes something darker: a rhetorical laundering of violence, a justification masquerading as analysis. Eight Suzuki, the self-styled Japanese anti-cult crusader journalist, has just crossed that threshold. In his latest X post, Suzuki repeats that Shinzo Abe “crossed a line” by sending a message to a 2021 event connected with the Unification Church, and that this act triggered Tetsuya Yamagami’s decision to assassinate him. Worse, Suzuki notes (and may appear to implicitly praise) the killer’s “broad, analytical perspective,” as though murder were a form of political commentary.

This is not journalism. It is moral inversion. And it demands a response.

Suzuki’s central claim is that Abe’s congratulatory message to a 2021 event of the Unification-Church-connected Universal Peace Federation (UPF) was the decisive act that provoked Yamagami, who had his own grudges against the Unification Church. But this is historical nonsense. Cooperation between Japanese conservatives and organizations connected with the Unification Church dates back to Abe’s grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi. It was not a secret, nor a scandal. It was part of a decades-long anti-Communist alliance that shaped Japanese politics in the Cold War era and beyond.

The International Federation for Victory over Communism, founded by Reverend Moon, worked hand in glove with the Liberal Democratic Party’s conservative faction. It supported electoral campaigns, pushed for anti-Communist policy, and mobilized against Soviet and Chinese espionage. By the late 1980s, leftist lawyers had organized an anti-Unification-Church movement precisely because the cooperation was so visible.

Against this backdrop, Abe’s 2021 message was not a rupture but a continuation of a routine practice. Politicians across the world, not all of them conservative—including Donald Trump, José Manuel Barroso, Enrico Letta, and countless Japanese leaders—sent similar messages to Unification-Church-connected events. These were appreciation for the UPF’s widely praised work on global peace education, not ideological conversions. To inflate Abe’s message into a “line crossed” is to rewrite history with a sly lawyer’s pen and a propagandist’s flair.

Abe’s message was somewhat banal. It was one of dozens sent by politicians across the globe to Unification-Church-connected events. It was part of a decades-old pattern of appreciation that spanned ideological divides. Socialist leaders, conservative pundits, prime ministers, presidents—all sent similar greetings.

To portray Abe’s message as a unique provocation is to ignore history. To portray it as the trigger for assassination is to distort causality. And to note the assassin’s “perspective” is to cross into moral bankruptcy.

Suzuki’s narrative is not only false, it is corrosive. It legitimizes violence as political critique. It stigmatizes minority religions as social threats to be eradicated. And it elevates journalists and lawyers who peddle hate speech into heroes of conscience.

But Suzuki’s rhetoric does something more insidious. By framing Abe’s message as the trigger, he shifts responsibility for the assassination onto the victim. Abe, in Suzuki’s telling, looks as if he were guilty of his own death. The killer becomes a tragic analyst, a man of “perspective.” And Suzuki himself, along with other anti-cult lawyers and journalists, becomes the heroic conscience who “warned” Abe but failed to prevent him from sending the message.

This is grotesque. It is the rhetorical equivalent of blaming a woman for wearing the wrong dress, or a minority for existing in the wrong neighborhood. It is victim-blaming elevated to political theory.

And it is dangerous. Because Suzuki unwittingly admits the truth. He writes that Yamagami had been reading, “in real time,” Suzuki’s own series of investigative reports slandering the Unification Church and it political connections. The killer, Suzuki boasts, was consuming his articles in “Daily Cult Newspaper, Weekly Asahi, Weekly Diamond, Weekly Toyo Keizai, Harbor Business Online, and more.”

Pause on that. The assassin is depicted as marinating in Suzuki’s flood of anti-cult polemics. He was absorbing a steady diet of articles that portrayed the Unification Church as an evil organization and conservative politicians as complicit. I don’t know whether this is true, but Suzuki himself says it.

Obviously, I am not arguing that hate speech and fabricated moral panics turn every reader into a murderer. Most people exposed to them simply absorb the prejudice, perhaps adopt discriminatory attitudes, and move on. But in weaker minds, in unstable individuals, hate speech can metastasize into violence. It creates an atmosphere in which minorities are stigmatized, politicians are demonized, and violence feels like justice.

Suzuki’s own words reveal the mechanism. Yamagami did not act in a vacuum. He acted in an environment saturated with anti-cult rhetoric, much of it authored by Suzuki himself. If Suzuki is hunting for responsibility, he does not need Abe’s photograph. He needs a mirror.

The question we must ask is simple: when does reporting cross the line into hate speech? Suzuki’s own admission provides the answer. When a killer consumes dozens of articles portraying a minority as malignant and a politician as complicit, and then acts on that narrative, the line has been crossed.

Suzuki cannot wash his hands of this. He cannot blame Abe for sending a routine message. He cannot praise the killer for his “perspective.” He cannot elevate himself as the prophet who warned but was ignored. He must confront his own ugly face in the mirror.

Anti-cultism internationally is part of the broader danger of hate speech masquerading as journalism. Minority religions become scapegoats. Politicians who support them become targets. Violence becomes commentary.

Suzuki’s rhetoric is a case study in how authoritarian logic spreads: redefine routine cooperation as scandal, redefine victims as guilty, redefine killers as analysts, and redefine hate speech as investigative reporting. It is the weaponization of language, the laundering of prejudice, the potential justification of violence.

We must resist it. We must expose it. And we must insist that responsibility lies less with a politician who sent a message than with those who had flooded the atmosphere with hate and created the moral panic that inspired the assassin.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.