The earlier stories of the popular detective series were written by a secular humanist. But the Stratemeyer Syndicate made them into a Christian answer to “bad” dime novels.

by Massimo Introvigne

Can you name the detective stories characters who have reached the largest number of readers in the world? The answer is not easy, since a distinction has to be made between short stories and book-length novels. But “Sherlock Holmes” would be the wrong answer at any rate.

If we count the number of stories and their readers, a better answer may refer to Nick Carter, the detective created in 1886 by John R. Coryell (1848–1924) who was featured in several thousand stories. The most famous Nick Carter stories were written by Frederic Van Rensselaer Dey (1861–1922) in the golden age of the dime novel, from the 1890s to World War I. Dey committed suicide in 1922, a victim of the dime novel crisis.

If we do not consider short stories, and focus on book-length novels (but include short books), the main contenders would be Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys. Both were produced by the same workshop, the Stratemeyer Syndicate, an ingenuous creation of Edward Stratemeyer (1862–1930), who had authored some famous Nick Carter stories. Together, the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys books may have sold more than a hundred million copies internationally, from their origins to the present day.

Stratemeyer had learned the art at the Street & Smith publishing house, the home of Nick Carter. The keystone of popular detective literature is seriality. Its consumers love to find the same characters and the same situations in different stories. In the early 20th-century market, if a character was really successful, demand, after a while, overwhelmed supply. The public was willing to buy one Nick Carter story a week; but no dime novel Stakhanovist had the time to write that many.

The solution? Have a score of different writers sign “Nick Carter” or “The Author of Nick Carter,” bound by contracts that prevented them from revealing their connection to the popular detective to the public. With Nick Carter, the operation succeeded so well that it was only by rummaging through the Street & Smith archives that the character’s leading scholar, my good friend J. Randolph Cox (1936–2021), was able to reconnect almost every known story about the American detective to an author.

Stratemeyer, one of the authors who signed “Nick Carter,” did not have the resources to launch a new publishing house. When, after World War I, the golden age of the dime novel ended in the United States (although it continued up to World War II in France, and even beyond in Canada), he set up on his own, and moved on to series published in 200-page volumes, including the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew.

Stratemeyer nevertheless maintained the idea of creating fictitious “authors,” behind whom different writers could hide. He operated a “syndicate,” an idea borrowed from the world of comics. He produced, typeset, and sold ready-made plates to publishers, mostly to Grosset & Dunlap. When he died in 1930, his heirs sold first a part of the titles and then the syndicate itself to a giant of international publishing, Simon & Schuster.

Stratemeyer wanted to make money. However, those who have studied his papers have concluded that it also had a religious motivation. He was a devout Protestant who avoided drinking, smoking, and immorality in general. He believed that Christianity was under assault from a secular popular culture, and most detective novels were corrupting their readers and alienating them from Christian values.

He wanted the Stratemeyer Syndicate to produce literature that offered the thrill of the detective story, but without too much blood and violence. He invented the detective stories for children, although they were read by adults as well.

He did not please everybody. The Boy Scouts of America accused him of introducing children to the dangerous world of detective stories, which could not be rescued by Stratemeyer’s good intentions. After his death, critics found in the Hardy Boys class and race prejudices, and the earlier books are no longer regarded as politically correct todays. Revised and amended editions are being printed, which does not please the old fans and collectors.

This is now, however. Back then, the formula made Stratemeyer a millionaire, and he was dubbed “the Rockefeller of popular literature.” He launched teenage detectives Nancy Drew (who attracted girls) and Frank and Joe Hardy (intended rather for boys, at least at the outset) into the Olympus of the most widely read and loved characters in the world.

For the Hardy Boys, he indicated as author one “Franklin W. Dixon,” and even circulated fictitious biographies of the supposedly reclusive writer. Strict contracts prevented the Stratemeyer authors from revealing themselves, and the secret was kept until the 1960s.

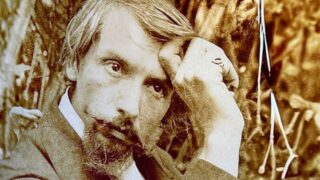

Today we know that the author of the first sixteen stories, from the historical “The Tower Treasure” of 1927 to “The Secret Warning” of 1938, and of four other volumes between 1943 and 1947 (one attributed to his wife for tax reasons), was Leslie McFarlane (1902–1977). He was a Canadian writer respected in his country as the author of celebrated short stories as well as the father of well-known hockey commentator Brian McFarlane.

With good reason, then, McFarlane introduced himself shortly before his death in an autobiographical volume as “the real Franklin W. Dixon,” even though several other authors signed stories under the same pseudonym; and, until Stratemeyer’s death in 1930, many “syndicated” writers turned short two- or three-page plots prepared by their employer into 200-page novels.

However, the early Hardy Boys owe much of their success to McFarlane’s ability to create entertaining and humorous texts. McFarlane was a secular humanist, but accepted to play Stratemeyer’s game and imbued the imaginary city of Bayport, where the Hardy Boys were supposed to live, with the typical values of a small American town, hard-working, slightly puritanical, and Protestant.

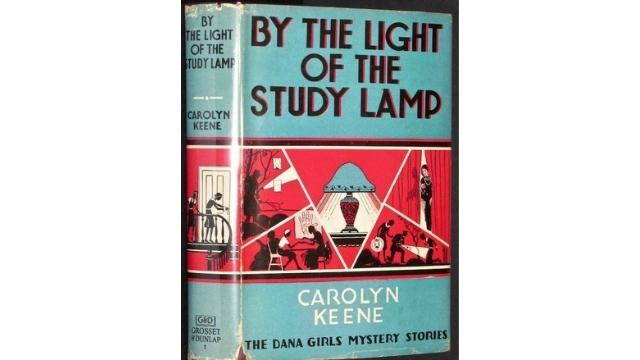

For Nancy Drew, Stratemeyer created a fictitious “Carolyn Keene,” and claimed she was the author of the stories. One of many writers who wrote as “Carolyn Keene” was McFarlane himself. Under the same name, he also produced for Stratemeyer the first four stories about the Dana Girls, who became in turn popular but never as famous as Nancy Drew or the Hardy Boys. In private, McFarlane ironized on the extreme puritanism requested for the Dana Girls by the pious Stratemeyer, while the Hardy Boys at least were allowed to have chaste girlfriends.

McFarlane was a quintessentially Canadian writer, even though he lived for some time in Los Angeles and Florida, with multiple skills. He dedicated the last part of his life mostly to cinema and television, and one of his documentaries was even nominated for an Academy Award.

Like other writers, McFarlane considered his detective stories for children to be minor works, hoped to be remembered for his Canadian stories and poetry, and confessed that sometimes he hated the Hardy Boys, although they had allowed him to survive in the difficult times of the Great Depression. These feelings are reminiscent of those of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) towards Sherlock Holmes.

The secular McFarlane, however, maintained fond memories of the arch-Christian Stratemeyer. He never complained about having sold for one hundred dollars a book manuscripts that earned Stratemeyer millions in royalties. It was the law of the syndicates of the time, which guaranteed poor writers the egg of survival today while depriving them of any hope of a hen tomorrow. Nor did anonymity displease McFarlane, who was almost ashamed of his detective stories and preferred to keep company with “serious” writers.

In the last part of his life, while the academia was rediscovering both dime novels and other forms of popular culture, McFarlane somewhat reconciled with the Hardy Boys, revealed his role in writing their stories, and concluded that being loved and respected by young readers was about as good as a writer could get. He was not too upset either about having had to sacrifice his secular ideas to participate in Stratemeyer’s crusade defending Christianity from hostile popular culture. He believed he did it in a gentle way, without sacrificing the entertaining value of the characters. Generations of readers agreed with him.