In the Roaring Twenties, the Polish painter was the quintessential Paris’ “bad girl.” Then, she met a mysterious French nun in Italy.

by Massimo Introvigne

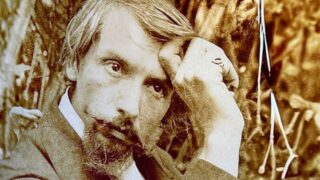

From 14 to 22 October 2023, the XIV Florence Biennale honored the Polish painter Tamara de Lempicka (1898–1980) with several events and an art award. The recent Biennale offers an opportunity to reflect on a rarely discussed part of the painter’s scandalous life: her relationship with religion.

Tamara de Lempicka was born in Warsaw into a wealthy Catholic Polish family. After a childhood spent in luxury and fashionable European resorts, she married lawyer Tadeusz Lempicki (1888-1951), a gentleman of distinguished family and impeccable manners, but of meager means. The lavish wedding was celebrated (at Tamara’s family’s expenses) in the Catholic chapel of the Knights of Malta in St. Petersburg in 1916, on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution.

After the Revolution Tadeusz, hostile to the new regime, was arrested. Thanks to her friendships in diplomatic circles, his wife managed to get him freed and escape Soviet Russia. The newlyweds settled in Paris, where in 1920 Tamara gave birth to her daughter Kizette (1920 –2001), who will become the model for some of her most famous paintings.

In Paris, Tamara decided to become a painter. She studied with the Symbolist artist Maurice Denis (1870–1943), a pious Catholic, and with the Cubist painter, of quite different views, André Lhote (1885–1962). The year 1922 brought her the first exhibition and success, which led Tamara, between Paris and Italy, to immerse herself in the atmosphere of the “Roaring Twenties.” She went through numerous and multiple erotic liaisons with both men and women, all of whom were consigned to posterity in her elegant portraits, executed in a unique style somewhere between her two masters, i.e., between Symbolism and Cubism.

This period also included, in 1926, the episode for which she is best known in Italy. Unique among the many famous women invited by the poet and famous womanizer to his Vittoriale residence in Gardone Riviera on Lake Garda, Tamara refused to give herself to Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938). Documents suggest for this refusal a rather unromantic explanation. The Polish artist, reached by rumors that the poet had contracted syphilis, seriously feared being infected. D’Annunzio or not, however, her husband Tadeusz in 1928 decided that her constant infidelities were no longer tolerable and divorced her.

Tamara married again with one of the most prominent collectors of her paintings, Hungarian Baron Raoul Kuffner (1886–1961), who also adopted Kizette, to whom he will pass on the title of Baroness. Although having previously shown some sympathy to a right-wing movement, the Action Française, Tamara detested Nazism. She convinced the Baron to move to the United States, where the artist, widowed since 1961, would remain until 1978.

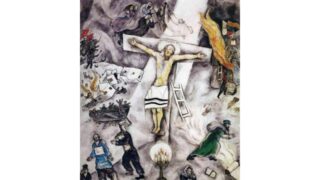

In 1935, while preparing a first trip to America, Tamara experienced depression and spent time in the spa resort of Salsomaggiore, Italy, where she sought relief in treatments. Here, quite unexpectedly, she somewhat reconnected with the Catholic religion of her childhood. She knocked on the door of a convent in Parma and was received by the Mother Superior, who, as she will later report in several interviews, just stared at her with a look that contained “all the suffering in the world.”

Tamara was leaving for New York, where she was staying at the Ritz, but rented an “old and dusty studio, with a cat and a chair” to paint. And here again—according to two lengthy interviews she gave in 1978 and 1979—on the chair one day Mother Superior appeared. However, the nun had never moved from Parma. According to the artist, Mother Superior remained in the New York studio for three weeks, talking to Tamara and allowing herself to be portrayed. She disappeared only when the small painting “Mother Superior” was finished. Or so Tamara claimed.

Both Tamara and her husband, Baron Kuffner, considered “Mother Superior” to be the artist’s best work. The painter would not agree to sell it for any amount of money, eventually donating it to the Museum of Fine Arts in Nantes, which had been the first museum to purchase her paintings. Critics did not always agree: the American Charles Phillips would speak of “low-grade emotionalism” and “glycerin tears,” dismissing the New York account of the nun’s bilocation as a tall tale or a hallucination.

Artistic judgment, of course, depends on many factors. Sometimes perhaps there is no lack of ideological bias that leads to the conclusion that the “great” Lempicka was the one of the “crazy years” and portraits of strippers and prostitutes. When she became the more placid Baroness Kuffner, in the eyes of some critics she became somewhat repetitious and less interesting. Even Hollywood is divided: Madonna collects her transgressive Paris paintings: Jack Nicholson loves her more sedate works from later decades.

Nun or not, there is no evidence that Lempicka became a practicing Catholic after the Salsomaggiore experience. However, some interesting details have emerged regarding the last years of her life, when in 1978 she moved to Cuernavaca, Mexico, and became involved with the young sculptor Victor Manuel Contreras (1941–2023), who died in May this year. Having become the 80-year-old Baroness’ confidant, Contreras told of her regular attendance at Mass and recitation of the Rosary in the last two years of her life. Tamara died in her sleep on March 18, 1980, but left precise arrangements, which Contreras took charge of enforcing, for a Catholic funeral and a novena of daily Masses between her cremation and the flight of her friends and daughter to the Popocatepetl volcano, where she had asked that her ashes be scattered. It was a theatrical, artist’s gesture, but not incompatible with Catholicism, since the Catholic Church had allowed cremation since 1963. It we believe Contreras, Tamara’s rosary would even have been at the core of extraordinary phenomena that happened after her death.

Of course, Tamara loved to create myths and legends around herself, and it is difficult to discern what is true from what is false or mythological. However, one should not censor the religious and Catholic episodes of her life to preserve only the image of the “bad girl” of the 1920s, which was not the only face of the artist.

As for Mother Superior, she really existed. After in an article I wrote in 2013, I suggested that local scholars in Italy should try to identify the nun in the Parma-Salsomaggiore area, two Italian researchers, Roberto Boccalon and Chiara Luzi, took my challenge. In a 2015 article they offered persuasive evidence that Mother Superior was Mother Thérèse Delphine (Eugénie Rosalie Capdevielle, 1874–1954) of the Daughters of the Cross, who lived in nearby Parma when Tamara was in Salsomaggiore. The French nun was, by all accounts, an impressive character. Mother Superior was thus not a figment of Tamara’s imagination. On how much she changed her life, the jury is still out.