An article in “Seiron” reveals unknown details about Shinzo Abe’s assassin and his mother, which run counter to the standard anti-Unification-Church narrative.

by Massimo Introvigne

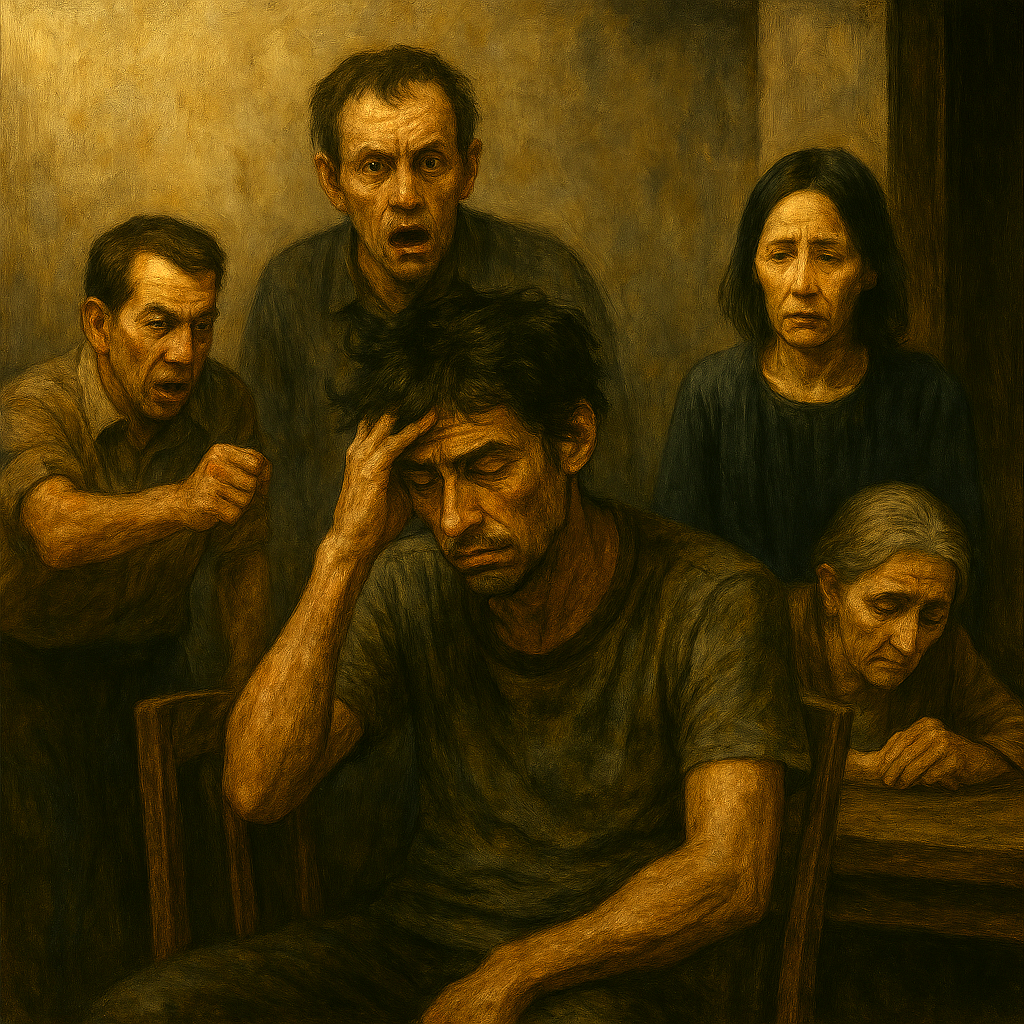

For nearly four years, Japan has lived inside a story that was too perfectly shaped to be true. It was a narrative that required no nuance, no psychological depth, and no curiosity about the messy realities of human life. A mother ruined by a “cult,” a family plunged into poverty, a son driven to despair, and a former Prime Minister whose death could be explained in a single, convenient sentence: the Unification Church destroyed a household, and the son struck back. It was a morality play so tidy that it practically wrote itself. And because it was tidy, it was irresistible.

But tidy stories are often lies of omission. In the February 2026 issue of “Seiron,” conservative commentator and X‑platform fact‑checker Fumihiro Kato detonated that lie with a long, unflinching reconstruction of the Yamagami family’s history. Over the past several years, Kato has become an influential voice in Japan’s online conservative sphere, known for his meticulous document-based fact-checking, his willingness to challenge media consensus, including on the Unification Church issue, and his refusal to accept narratives that collapse complexity into ideology. His followers on X treat him as a kind of digital ombudsman, a man who reads the footnotes the mainstream press ignores. And in this case, he has read them all.

Kato’s article, “The Deep Darkness of the Yamagami Family—The True Motive Behind Abe’s Assassin,” is not a defense of the Unification Church, nor a rehabilitation of the assassin, nor a political manifesto. It is something far more provocative: an insistence on complexity in a public discourse that has preferred simplicity. In doing so, it exposes how much of the prevailing narrative was built on the irresistible seduction of a moral fable rather than on facts.

From the opening paragraphs, Kato makes clear that the prosecution and the defense have both simplified the story to suit their purposes. Prosecutors insist that Shinzo Abe had “no connection whatsoever” to the defendant Tetsuya Yamagami’s family circumstances. The defense insists that the family was “destroyed” by the mother’s donations to the Unification Church. The media, predictably, embraced the latter. It was the more dramatic story, the more politically advantageous to the left-leaning press, and the least effort to understand. But Kato’s reconstruction shows that the truth is neither of these narratives—and is far more disturbing than either side has admitted.

He begins by dismantling the foundational myth that the Yamagami family was destroyed by religion. Long before the mother encountered the Unification Church, the household was already collapsing under the weight of a father’s alcoholism, a grandfather’s rage, a grandmother’s death, and— most crucially—a firstborn son whose severe illness and violent behavior turned daily life into a battlefield. The father, once a director in the civil engineering firm run by his wife’s father, fell into conflict with his father-in-law, quit his job, and began drinking heavily. The maternal grandmother died of leukemia. The eldest son was diagnosed with lymphoma as an infant, then later developed a tumor behind his eye that required brain surgery and left him blind in one eye. The doctor’s grim warnings—that the cancer might grow until the eyeball “popped out”—left the mother psychologically shattered.

This is the emotional landscape in which the mother turned to religion. She first joined (and donated to) Jissen Rinri Koseikai, not the Unification Church, and her early involvement in this organization was driven not by doctrine but by desperation. Jissen Rinri Koseikai (Association of Practical Ethics), well-known for its early-morning meetings where members pledge to live each day with compassion and gratitude, claims to be non-religious, although scholars have argued for its Buddhist roots. Yamagami’s mother testified that the association’s morning meetings “purified” her irritation and allowed her to be kinder to her children. Her husband, however, opposed her participation and her “purifying offerings,” and the household descended further into conflict. The paternal uncle later accused her of neglecting the children, but Kato notes that the mother disputes his account, and the chronology is unclear. What is clear is that the family was already in crisis, and religion was not the cause.

The father’s suicide in 1984—he jumped from a height while suffering from alcoholism and depression—plunged the household into deeper chaos. The mother, pregnant with her third child, became the sole provider. The family moved to Nara, where the maternal grandfather’s construction business thrived during the bubble economy. The children, including the future assassin, grew up not in poverty but in relative comfort. The defendant himself later wrote on X: “It wasn’t poverty—if anything, we were well‑off.” They received expensive toys. They lived in a large home. The mother became an executive in the family company.

This is not the picture the media painted. But it is the picture Kato insists we confront.

The eldest son’s second major illness in 1989—the tumor behind the eye—pushed the mother into more profound psychological distress. It was in this state, Kato notes, that she encountered the “Korean Japanese Church” (Kan-Nichi-jin Kyokai), a branch of the Unification Church that was not part of its standard Japanese congregational structure and was operated by Koreans primarily for fellow Koreans living in Japan. She donated 20 million yen.

But Kato’s source, the former church leader close to the Yamagami family he calls “A,” emphasizes that the mother’s religiosity was not uniquely tied to the Unification Church. “Had she encountered a different religion,” “A” says, “she likely would have embraced that faith and made donations there as well.” Her motivation was not ideology but fear—fear for her son, fear of the future, fear of a household she could no longer control.

The Korean–Japanese congregation, Kato notes, as evidenced by the testimony of “A,” was poorly equipped to understand Japanese family dynamics. Its Korean leaders did not grasp the cultural nuances of Japanese motherhood, nor the emotional turmoil inside the Yamagami home and the crisis in the woman’s personal life. Her father, discovering her donations in 1994, reacted with despair and even pulled a kitchen knife in a moment of rage. The defendant later wrote that his grandfather’s mental deterioration, combined with the collapse of the bubble economy, left him unstable and prone to urging the children to “pack their things” and leave. The mother, ironically, became the one who protected them.

By 1997, the family business was failing. The Korean–Japanese congregation dissolved. The mother formally joined the Unification Church—a detail often misreported, as media accounts typically claim she joined in 1991. The defendant attended a church seminar but was not pressured to convert to the faith. He later wrote that “what makes sense, makes sense,” but did not report improper pressure to join by his mother or others.

The real crisis, Kato argues, was not religious but familial. The eldest son, intellectually gifted but socially impaired, became violently unstable. He attacked his mother with a knife. He broke her ribs. He destroyed property. He threatened suicide. He also stormed into his mother’s church, intending to kill “A” (who, happily, was not present) with a knife, then kill himself. Doctors diagnosed him with a severe developmental disorder. The mother lived in constant fear. Kato notes that “A” tried to help the disturbed brother in many ways, for which Tetsuya expressed gratitude by presenting the church leader with a pair of sneakers.

Tetsuya, however, was spiraling into suicidal ideation of his own. He declined to attend university, saying he “intended to die anyway.” He left home in 2001.

This is the household the media reduced to a “cult-destroyed family.” Kato’s reconstruction shows something far more tragic: a family destroyed by illness, violence, and psychological collapse.

The turning point in Kato’s narrative—and the part most inconvenient for the anti-Unification Church storyline—is the refund process. When “A” became the mother’s church leader in 2002, he discovered that her donations were far larger than anyone had realized. He interviewed her, calculated the total at 130 million yen, and negotiated a refund of 50 million yen. The mother resisted the refund, believing her donations had meaning. “A” insisted. The defendant was chosen as the family representative. Refunds began in 2005, the year in which Tetsuya Yamagami attempted suicide, for causes, he testified, unrelated to the Unification Church. Eventually, the agreed sum of 50 million yen was fully refunded.

This is not the behavior of a predatory institution. It is the behavior of an institution attempting, however imperfectly, to help.

Kato emphasizes that the family was not impoverished during this period. The mother worked in building management and cleaning. The family received 300,000 to 400,000 yen per month in income. The sister attended private school and later university on scholarship. The mother drove a car. The home was messy due to the brother’s violence and not lavish, but not destitute. There was no welfare assistance. The defendant himself lived independently for years. The media’s portrait of a family crushed into poverty by religious exploitation does not match the facts.

Kato’s most provocative claim is that by 2005, the defendant had emotionally closed the chapter on his mother’s donations. His email exchanges with “A” reveal a young man struggling with depression, isolation, and a sense of inadequacy—but not with anger toward the church. He asked “A” whether he found him “sane.” He lamented his inability to form relationships. He described himself as someone who could only live if others pitied him. He expressed no resentment toward the Unification Church or its founder. “A” concluded that the issue of the mother’s faith “was over” for him.

But the story did not end there. The defendant failed to build stable relationships. He separated from his girlfriend. He withdrew from society. “A,” who had sincerely and constantly helped, moved to South Korea. The elder brother committed suicide in 2006, apologizing to his sister before his death. The defendant’s isolation deepened. By 2020, he was posting increasingly delusional comments on the blog of “cult watcher” journalist Kazuhiro Yonemoto, who warned him that his thinking was “pathologically obsessive.”

Kato suggests that the defendant’s delusions were fueled by misunderstandings about his mother’s later activities. She traveled to Cheongpyeong in South Korea, a sacred site associated with the Unification Church, but not at the church’s instruction or request. The defendant assumed she was being coerced into going to Korea or making donations, which was actually not true. He did not ask her. He did not verify. He just assumed. His suspicions hardened into conviction.

This is the psychological spiral Kato insists we confront: a man who built a private mythology out of misunderstanding, isolation, and despair.

The leap from resentment toward the church to the decision to shoot Shinzo Abe remains the most haunting question in the entire case. Kato does not pretend to solve it, but he raises the unsettling possibility that someone—online or offline—nudged the defendant toward a more symbolically potent target. The defendant himself wrote that he “didn’t hate Abe.” He exposed himself to anti-Abe discourse to “heighten his motivation.” He believed he would “gain understanding” by shooting Abe.

What Kato ultimately exposes is the intellectual laziness of a media ecosystem that preferred a morality tale to a tragedy. The real scandal, he implies, is not what the Unification Church did, but what the media refused to see: a family destroyed not by doctrine but by illness, violence, miscommunication, and a deluded son who mistook his own narrative for reality.

In the end, the assassination of Shinzo Abe was not the outcome of religious exploitation. It was the catastrophic collision of personal delusion, social isolation, and a national narrative eager to find a villain in the Unification Church and reluctant to confront the uncomfortable truth that sometimes the darkest tragedies have no simple cause, no clear moral, and no institution to blame.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.