Now a refugee in Europe, Qelbinur has decided to break her silence and tell Bitter Winter the reality about Han Chinese “relatives” sent to Xinjiang to live in the homes of Uyghurs

by Ruth Ingram

Qelbinur Sidik is one of the few Uyghurs to have escaped Xinjiang to bear witness firsthand to the violence, the brutality, and the sadism of the so-called “transformation through re-education” camps, and the Orwellian politics that conceived not only these but a whole raft of grotesque strategies to subdue the people of north west China.

One of these schemes was “Pair up and become family,” the forcible billeting of one million cadres to eat, cook, study, live, and sleep together with Uyghurs in their homes, which to this day continues to strike terror into the heart of every woman and girl who has been subjected to its cruelty, and in the minds of some is none other than institutionalized rape and sexual abuse.

Since she fled to Europe a matter of months ago, tattered emotionally and physically, Qelbinur has been mustering her courage to speak about what she has seen and heard. She only escaped incarceration herself because she agreed to teach in a camp, and lives with an overwhelming burden to tell the world.

By some miracle, she escaped the nightmare in December last year. Against all odds, she had been able to retrieve her passport and travel for medical treatment, on the condition that her husband remain behind and she promise to return forthwith.

But deeply traumatized by what she has been through, she cannot bring herself to go back. She arrived shocked, grieved, and profoundly shaken by her experiences. Paralyzed by the events of the past three years, she spent her first few months of freedom unable to speak to anyone. But to relieve this overwhelming burden, she started to talk. A relative told her that she had been spared by God to tell the story, but she had no idea what to say or where to start, and would anyone believe her?

Few people have emerged from Xinjiang to tell their story, and with every piece of evidence, conjecture, or surmise produced by academics and researchers, the Chinese government is quick to shoot them down with the accusation that they have never lived there or seen what they are accusing Beijing of, first hand.

But Qelbinur has seen everything with her own eyes. From day one of Chen Quanguo’s iron fist which began to choke the life out of her people when he was transferred from Tibet in 2016, she saw them terrorized into compliance, their culture and language reduced to a quaint pit stop on the tourist trail for the millions of Han Chinese encouraged to spend their holidays in the “exotic” north west, and their religion become a poison chalice which they drank at their peril.

Qelbinur has tentatively started to speak openly about her experiences, and with every retelling the ordeal is revived as if it were yesterday.

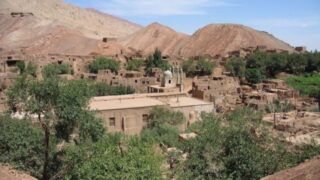

The multi-faceted Pinteresque drama started to unfold as Chen’s noose tightened and for those living through it, the changes were almost imperceptible. Someone would disappear only to reappear at the weekly meeting a week later to recite a confession. “He’s gone for study,” people might remark jokingly about a son or a relative whose attendance at the flag raising might have been less than enthusiastic. But gradually and insidiously, the “stays” would get longer, the “recommendation” to have free health checks more insistent, the reams of razor wire more menacing, and the empty houses with seals and padlocks ominously the norm. Groups of officials with clipboards and name tags scurried about the housing complexes and other motley gaggles marched through the lanes swinging first axe handles, then baseball batons, and then long poles with medieval spikes or spears. Others were posted at street corners clutching red pennants.

They were told universally that Xinjiang was on a “war footing.” They must stay alert.

Into this new regime that crept up with pernicious stealth sprung the “Pair up and become family” program. As if millions of surveillance cameras, facial, voice and gait recognition, airport security and ID card checks everywhere you went and a compulsory monitoring app on your phone were not enough, into the drama pounced an ingenious plan to monitor everyone from within. How would it be if every Uyghur family had a Han Chinese “relative” who would visit, live with you, sleep with you, teach you, and monitor your every movement and every thought?

To this end, a million cadres were mobilized to form the second front. The policy of acculturation was in a new phase.

The popular one-day May 1st Labour Day holiday had already been re-styled “National Ethnic Unity Day” in Xinjiang, and combined in 2016 with a day of inter-ethnic activities of eating, dancing, and cooking together. Government staff began to be paired with villagers, with the aim of stemming the “plague of sabotage activities of the ‘three evil forces’ of separatism, extremism and terrorism.”

In May 2017, government officials announced a new program to celebrate a whole week of inter-ethnic activities, entitled the “five togethers” (五个一).

Qelbinur takes up the story: “We were asked to ‘live together, cook together, eat together, learn together, sleep together’ with Han cadres assigned by the local government. Women must have a male Han cadre ‘relative’ and men must have a Han female ‘relative,’” she said.

“At first, they told us we should live together for one week every three months. But this soon increased to a week once a month,” she explained. “The scheme shocked me. I could understand working, studying, and eating together but why should we live together and sleep together with them at our home?”

And this is when she began to suspect the plan was assimilation. “We had no option but to accept the arrangements, and no right to object,” she said bitterly.

Beijing confirmed the sweeping nature of the changes in December 2017, with a bombshell announcement designating “Ethnic Unity Week,” and extending the “relatives” program to the enforced pairing up and billeting of one million cadres to their new families who from henceforth would be treated as their “relatives.”

Every three months, they would be ordered not only to live, eat and study together for a week but welcome the Han Chinese visitors into their homes and their hearts without a whimper. Resistance would be futile and deemed subversive. Very soon the arrangement would become a week every month.

Qelbinur’s account from exile of hosting her “relative” is sharply at odds with that of Beijing’s mouthpiece Global Times. Whereas the publication writes of people from different ethnic groups feeling “the warmth of the Party and governments through ethnic unity activities,” and villagers who are so keen to welcome the uninvited “guests” that they “cleaned the rooms and set up a stove at home” before four “relatives” descended on them. One villager even installed new electric sockets and prepared fresh rolls of tissue outside his toilet for the four government employees. “Many villagers,” according to The Global Times, “cleaned their houses, prepared quilts and cooked food after they heard about the visit of their ‘relatives,” and one even “shed tears” and said that they did not want the official to leave.

But Qelbinur has a different version.

Her husband’s 56-year-old boss and his wife became their “relatives”. The boss, a father of one, came at first with his wife, but with the excuse that they did not want to burden Qelbinur, the wife stopped coming.

His whole purpose, as far as Qelbinur could discern, was to worm his way into her bed. Lewd and suggestive comments one after the other, requests of her husband that the “relative” wanted to “kiss his wife,” and share a bed to “keep warm”, were met with pathetic laughter from the man terrified of losing his job, or worse still ending up in a camp, and more “playful” advances from the “relative,” which Qelbinur managed to gently rebuff without antagonizing him.

A major row with her husband over this in Uyghur, when she accused him of not standing up for her and told him that if she was made to sleep with the “relative” she would “kill him,” was interrupted by the Han man asking what was going on. She excused their quarrel, and continued to smilingly allow him to do anything a real relative would have done. “Of course, since he’s a relative, he can legitimately kiss me, hug me, and sit next to me,” she said. “And we can’t do anything about it.”

The weeks were suffocating. He would stroke her face in front of her husband telling them how much he loved Uyghur food and Uyghur women. He insisted on addressing his conversation towards her due to her husband’s lack of Mandarin, and feigned an interest in her teaching him how to cook, how to use a knife and a wok, so that they could be alone in the kitchen. “He would strip down to his shorts and sexually harass me while I was cooking,” she explained, describing how he used the opportunity away from her husband to embrace her and grab her hands.

“If I dared to show disapproval, he would accuse me of not liking him,” she said. “He would insist I dance for or with him and sometimes he wanted me to sleep in his room. If my husband was not around, he would be excessively and revoltingly amorous, but I managed to escape by subtly declining his advances.”

He would worm his way slyly into their thoughts and opinions on politics, religion and the CCP. “He would never ask us straight if we were Muslims or prayed,” she recounted. “He was just like a fox. We had to deny everything. We had to be on our guard constantly in case we slipped up.” She dreaded the questions about pork and had her answer ready. She would have to eat it smilingly if he insisted, but she managed to convince him that the fattiness of both chicken and pork revolted her. “But he was so cunning and tried his best to catch us out.”

Despite all this Qelbinur felt her situation compared favorably with that in the south of the region, where most of the men had been taken to camps and women and their daughters were easy prey for men who were far from their own wives, some for months, even years at a time.

One of her friends returned from her stint in a remote village, where she had been billeted with eight Han Chinese male cadres who had been sent from inner China, and over dinner one night she recounted a catalogue of ill treatment and physical beatings meted out by these so-called volunteers when they were trying to teach Chinese to village children.

But this was mild compared with what followed. When the cadres used to get together to compare notes, the Chinese men would be in ecstasy over their exploits with village girls at night. “They never actually told my friend that they raped the girls, but the rapturous way they compared girls back home with these ‘compliant beauties’ spoke for itself,” said Qelbinur. Her friend told her how the male “relatives” gleefully and proudly recounted taking the daughters of their families upstairs in turns through the evenings and meeting no opposition. “How could they resist?” she complained. “Their fathers, brothers, and mothers were all in camps. They were powerless to repel the men and were terrified themselves of being taken away,” she said bitterly.

Sexual harassment and rape had become so commonplace in the capital Urumqi under this scheme that safeguards were later introduced billeting groups of three Uyghur women to one Han “relative.” But as far as Qelbinur knew, this scheme was never rolled out to the south. “I dread to think of what continued to happen to those poor women,” she said.

And as for Qelbinur, despite being safe in Europe, she has not been left alone. In spite of having a six-month visa, one month after her arrival she started receiving calls from the Chinese police and her school. “When are you coming back? Haven’t you been there long enough?” They would badger. By February, she was told her pension would stop if she was not back by March 1st. She received an angry call from her husband around that time telling her he had had enough of being hounded by the authorities because of her. Then silence until May when an outraged husband called her and told her he had divorced her according to Islamic law. “You are no wife of mine,” he yelled. He was being pursued by the police and family planning representative to discover what had become of her IUD. He had had enough and wanted rid of her.

Then just last week, out of the blue, the same family planning official called her and bombarded her with questions about her IUD. Where was it inserted? Which hospital? Did she have a copy of the certificate of insertion? If not, why not? Where was it? Did she still have the IUD now? If not when and where was it removed? Which hospital and more importantly which doctor dared to remove it without permission?

She knew truthful answers to these questions could incriminate many people and that doctors who removed IUD’s were taken to camps. She fobbed them off and put down the phone. “I am never free of them,” she says ruefully.

She lives still, as do millions of other Uyghur women, with lifelong scars inflicted by these very same savage birth control methods which for her had been distressing from day one. Her sleepless nights and long, painful days are full of flashbacks that so far time has not erased. She is writing a book. She says she will never stop speaking out and telling the world the secrets the CCP is determined to keep to itself, if only in part to lift the weight of those memories which cling unbearably to her.