As human rights atrocities envelop the globe, pleas not to forget the Uyghurs rang out from exiled poet Aziz Isa Elkun on UNESCO’s World Poetry Day, March 21st.

by Ruth Ingram

Barely a week has passed since Uyghur poet, Aziz Isa Elkun held forth on the Main Stage of London’s 53rd Book Fair, where 30,000 visitors crammed into the cavernous 19th century Olympia Exhibition Centre over three days, from March 12–14, to call attention to the persecution of writers and poets in his homeland.

More than one thousand exhibitors from around sixty-one nations gathered to network, gain insights into latest publishing trends, and plan the future of creative content, against a backdrop of seminars and panels to address everything from writer’s block to banned books and human rights.

As a member of English PEN, Elkun was one of more than one hundred speakers and panelists over the three days chosen to speak about the crisis facing Uyghurs in the loss not only of their culture and religion, but also their language, and the writers and poets who have been the bearers of their traditions and way of life down through the centuries.

Speaking to “Bitter Winter” on World Poetry Day, Elkun urged the world to remember the more than five hundred Uyghur poets sentenced to lengthy jail terms for their “crime of writing poems,” and the “severe extrajudicial persecution endured by Uyghur poets at the hands of the Chinese government.”

“Their only crime was writing poems in their God-given mother language, Uyghur,” he said.

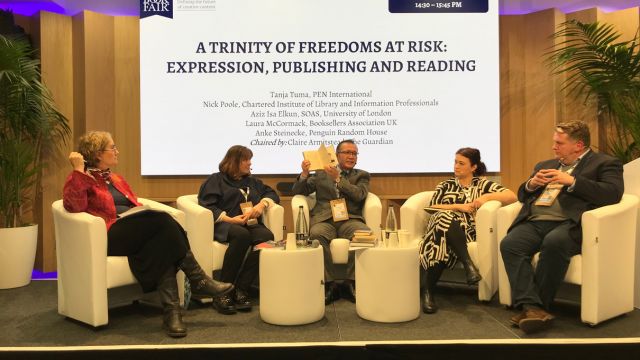

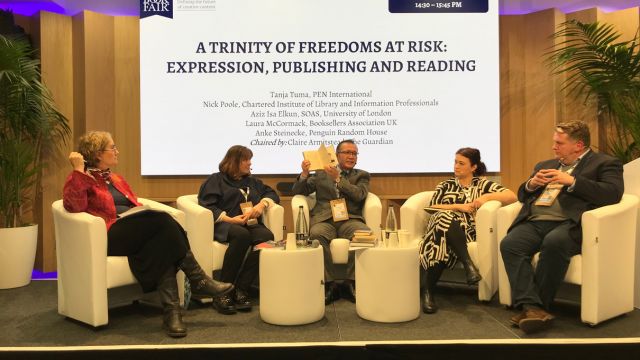

Addressing a forum entitled “A Trinity of Freedoms at Risk: Expression, Publishing and Reading,” Elkun joined panelists from around the world to condemn the universal creeping threats to freedom of expression, the liberty to publish and the right to read.

He cited events in his homeland, particularly since 2017 when Chen Quanguo, a new governor at the helm was charged by China’s leader Xi Jinping, with quelling dissent in the “restive” Uyghur region. Religious leaders, writers, educators, and academics were rounded up and together with more than one million Uyghurs and Turkic peoples of the province, were sent to so-called “Vocational Training Camps,” from which they were either sentenced to lengthy prison terms or moved onto forced labor around the country.

Elkun urged writers and publishers in the free world to stand up against increasing authoritarianism that he warned would bring “a disaster for humanity.” China was being “empowered” by the West to export the philosophy of Xi Jinping around the world, he warned. He called out the UN General Assembly for allowing Saudi Arabia and China to be elected onto the International Publishers Association. “How did this happen?” asked Elkun.

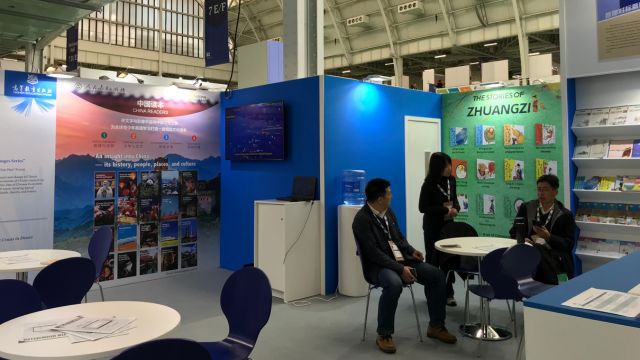

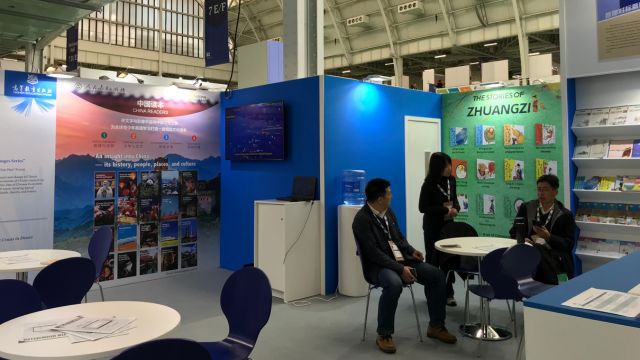

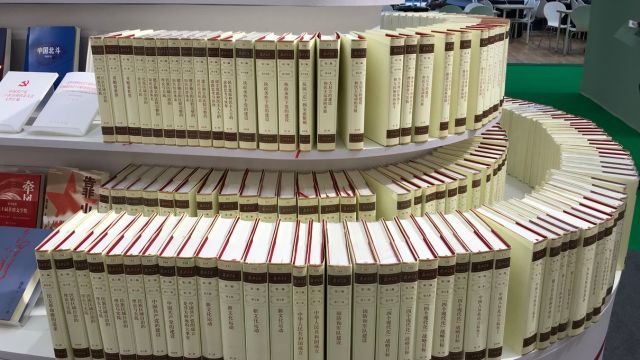

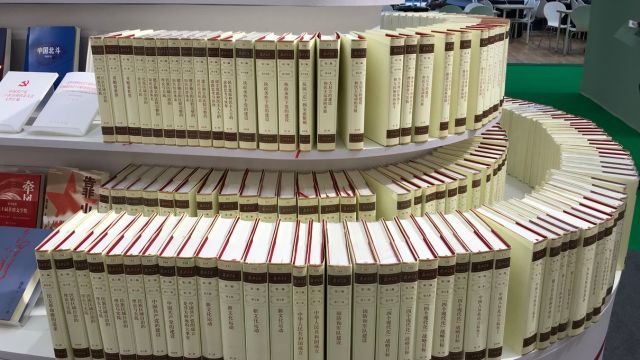

He urged the publishing industry not to put economy before ethics and to call out China’s linguistic hegemony in denying the so-called minority groups in the land a voice. “Uyghurs and other groups are facing an urgent danger,” he said, citing the 2012 London Book Fair where there had been many hundreds of Uyghur language books on display. “In the last three years there have been none.”

Enquiries of the five major Chinese publishing houses in the exhibition arena by “Bitter Winter” confirmed Elkun’s fears. “We have books written about the ‘minorities’ in China,” said one of the stallholders, echoed by the others. “But we simply didn’t have room for anything but books in the national language this year.” One stallholder stressed that she thought the “minorities” had books in their areas and that China’s policies towards them “were fair.”

Elkun said that no books, apart from translations of Xi Jinping’s speeches had been published in the Uyghur language in his homeland since 2018. “Every independent Uyghur bookshop has been closed,” he said. “This is quite simply cultural erosion.”

Addressing the crisis faced by the Uyghur people on World Poetry Day, a day set aside by UNESCO in 1999 to “support linguistic diversity through poetic expression and increase the opportunity for endangered languages to be heard,” Elkun singled out a handful of well-known poets whose freedom had been cut short by the clampdowns in his homeland.

“These poets, including prominent figures such as Abduqadir Jalalidin, Perhat Tursun, Ablet Abdureshid Berqi, Rahim Yasin Qaynami, Adil Tunyaz, and Gulnisa Imin Gulkhan, now find themselves behind bars,” said Elkun, “their only offense being the courageous act of sharing their voices through verse.”

Abduqadir Jalalidin is a renowned Uyghur poet, scholar, and literature professor at Xinjiang Normal University. He was detained without reason in 2018 and since then his whereabouts are unknown. When the verses reached the outside world, he was one year into a 13-year sentence imposed in 2019 for no obvious crime, according to the Uyghur Victims Database.

His poem, “No Road Back Home,” composed from his cell, was memorized by cellmates who, upon their release, recited it to prove to his family that he was still alive. An excerpt, translated by Uyghur poet and scientist Munawwar Abdulla, was a rare glimpse of life behind bars in China, talking of a “broken heart, aching and longing” to be with his love, “tormented with no strength to move,” “watching the seasons change through cracks and crevices.”

“I have no lover’s touch in this solitary corner, I have no amulet for each night that brings me terror, I have no thirst for anything but life. With anguished thoughts in crushing silence, I am bereft of hope.”

Perhat Tursun, one of the most celebrated contemporary Uyghur poets and writers, was detained around January 2018 said Elkun. In February 2020, reports emerged that the Chinese authorities had sentenced him to sixteen years in prison. His current situation is unknown.

“Let’s not blame life for being meaningless,” he writes in his poem “The Heart” translated by Elkun. “One day loneliness will reach its peak. Even if we can’t see how to achieve our desire, We can still shed silent tears.”

Gulnisa Imin Gulkhan, a renowned female poet, who had worked at the Chira High School as a Uyghur Literature teacher, was sentenced to seventeen and a half years in prison for her poems. According to the Chinese state, they were “spreading thoughts of separatism.”

An excerpt from her poem “The Tenth Night: The Sunless Sky,” translated by Elkun, refers to her observation of life in a women’s prison, where women with “dirty, cracked and bleeding hands” “don’t want to shed their tears.”

“They just want to lift their heads

They just want to gaze at the sunless sky.

Their troubles, their yearning

Their nightmares and sleepless nights

They want to talk about it with someone on the outside.”

Ablet Abdurishit Berqi is a prominent poet and academic. He was an associate professor, and later conducted postdoctoral research at Haifa University (2014–16). After his return home, he was arrested and sentenced to thirteen years in jail.

Elkun shares an excerpt he translated from his work, “The Confession of a Poem.”

“It would not be a poem if it were detained

It would not be a poem if it were killed

It is not a poem for blind people

It is only for those with quick eyes.”

“The global community bears a critical responsibility to safeguard the Uyghur population and halt the atrocities perpetrated by China, tantamount to genocide. The prolonged impunity enjoyed by China for its egregious violations of human rights poses an alarming threat to global stability,” Elkun told “Bitter Winter.”

“It is imperative that we unite to defend the fundamental principle of freedom of expression, for none should face persecution merely for expressing themselves through poetry or any form of creative expression. Our collective aspiration for a world characterized by peace and universal happiness transcends boundaries of race, faith, color, and culture. Consequently, the international community must hold China unequivocally accountable for its genocidal campaign against the Uyghur people,” he said.