If guilty of sexual abuse, the leader deserves to be sentenced. But sensationalist TV shows poison the well and create discrimination against innocent believers.

by Massimo Introvigne

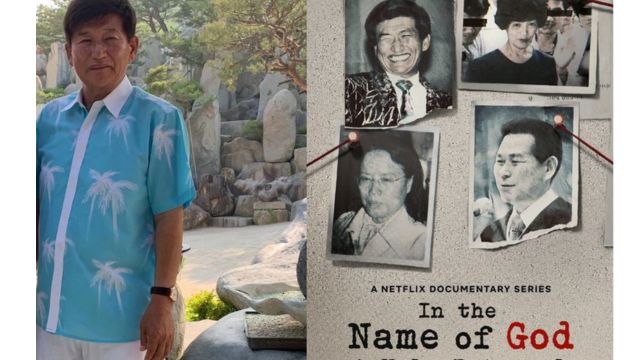

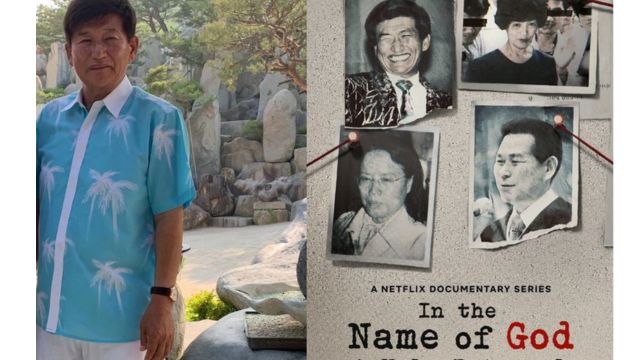

Only a handful of academics, including the undersigned, had studied the Korean Christian new religious movement Providence, also known as Christian Gospel Mission (CGM), before its leader, President Jung Myung Seok, who had spent ten years in jail between 2008 and 2018, was arrested again on October 4, 2022, following new accusations by two women. Even the second arrest, however, would have largely remained a domestic Korean matter, had not Netflix decided to focus on Jung and Providence in its TV miniseries “In the Name of God: A Holy Betrayal,” launched throughout the world in various languages on March 3, 2023.

As it happened in other cases, Netflix changed the equation. Korean politicians and media reacted to the TV series demanding an “exemplary” punishment of Jung, some of his lawyers renounced to his defense, Providence’s headquarters were raided again, and devotees not personally accused of any crime started to lose their jobs and being discriminated and bullied in different ways in several countries.

Before Netflix, Providence was an interesting matter of study for specialized scholars for sociological reasons. It confirmed the theory that new religious movements with a leader sentenced and jailed for sexual abuse (Jung is certainly not the only case) can nonetheless continue to exist and in some cases even grow. This is a variation of the well-known theory that movements can predict a wrong date for the end of the world and “when prophecy fails” end up gaining members rather than losing them.

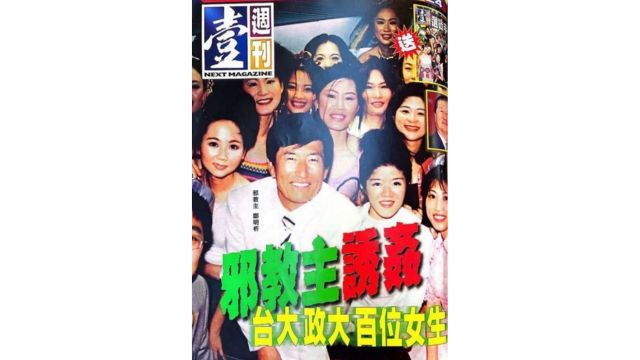

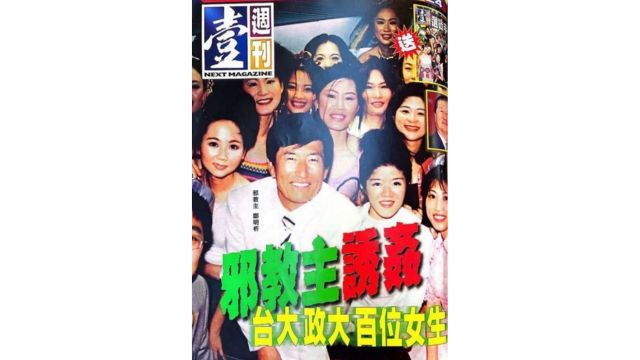

Providence proved that this may be the case particularly in Taiwan, where the movement continued to flourish among college students during the ten years of Jung’s detention and even after its second arrest. But what about Netflix? “Bitter Winter” has interviewed three Taiwanese scholars familiar with Providence and its growth in Taiwan. Li Yu-Chen is Chair Professor in The Graduate Institute of Religious Studies (GIRS) at National Chengchi University. She is a specialist in gender issues connected with religion. Hung Tak-Wai is a Research Fellow of the Research Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences of National Taiwan University. He specializes in the relationships between globalization, religion, and politics in East Asia. Lee Po-Han is a British-educated sociologist and Assistant Professor at National Taiwan University.

Giving voice to an opinion shared by all the interviewees, Hung clearly stated that “It is essential to hold individuals accountable for any crimes they may have committed.” The Taiwanese scholars agreed that in no case religious liberty may be an excuse for sexual abuse. If guilty, President Jung should be punished. On the other hand, Hung added, all defendants, including President Jung, “should be granted the fundamental right to a fair trial. This right is not conditional and should not be compromised due to an individual’s religious affiliation.”

The scholars expressed concern for the possibility that the Netflix series may make a fair trial, in the different degrees of judgement, more difficult. “We understand the significance of public opinion in shaping the narrative surrounding legal cases,” Hung said. “However, it is vital to remember the principles of the common law system, particularly the warnings against ‘perverting the course of justice.’ This principle emphasizes the importance of ensuring that judicial proceedings are free from external influence, including public and political pressure. It is essential to safeguard the integrity of the legal process to prevent undue interference.”

Lee said that, “As a human rights and gender studies researcher, I shall not comment on the ongoing criminal proceedings and have tried to retain my trust in the Korean criminal justice system, but I also should point out the danger of popular reactions.”

All three scholars have observed Providence in Taiwan rather than Korea. They have noted the perverse effect of Netflix, which created discrimination against Taiwanese devotees who are not personally accused of any crime. Li believes that the problem in Taiwanese society is older than Netflix. “New religious movements (NRMs),” she said, “often offer women greater opportunities for participation and management than traditional institutional religions. NRMs are often questioned or even attacked in Taiwanese society. In line with Chinese culture’s traditional attacks on ‘cults,’ this mostly happens through sexual scandals. This is a very interesting phenomenon, because female members already have a numerical advantage in NRMs, which means they have a high visibility.”

Li has studied the motivations of believers who joined Providence but “I use slander from outsiders as background information,” she added. “The problem is that members of Providence who are attacked by external forces are under great pressure, because no matter how they defend themselves or take legal action, outsiders can rake them over the ashes, like a stigmatization label that they carry with them, which is very annoying.”

Lee noted that “many Providence members in South Korea, Taiwan, and elsewhere, both men and women, have been affected and threatened online and in everyday life since ‘In the Name of God’ was released on Netflix. Understandably, most of these actions are asserted out of a ‘sense of justice’ for women who were said to have been abused and violated. However, such actions also have a detrimental impact on innocent Providence members, especially women, who are framed and labeled, regardless of their relationships with the controversy at issue, personal histories of faith and affiliation, and efforts made to commit to their religion. They have been described and humiliated, with strong hostility, as ‘stupid,’ ‘naïve,’ and ‘brainwashed’—and even ‘self-exploited,’ if some of them obtained administrative positions in the church. Despite the intention—whether protectionist, paternalistic or simply misogynistic—such framing not only completely denies the agency and subjectivity of these women but also results in widespread discrimination against them in the popular discourse.”

Female members who suffered no abuse in Providence reported that they were abused by Netflix and other media. “We would not see the same comments used against male members, Lee said, who may also receive hostile responses but at least are exempted from being dismissed as stupid and naive.”

While it is not uncommon that female members of NRMs are denied their agency and told their choices derive from “brainwashing,” what happened in the case of Providence was exceptional for its intensity, Li commented. “It is extremely rare that transnational attacks are so frequent and even affect the members’ job hunting and work. Providence comes from South Korea, and their religious debate has its own cultural background, but because the alleged ‘victims’ include female college students in Taiwan, the issue has been constantly raised here too. Most of the public will sympathize with the ‘victims,’ but as for the current members of the church, they are constantly ignored.”

As a well-known scholar of gender and religion, Li noted that “Taiwanese society’s attacks on Providence tend to focus on gender issues, especially on young, privileged girls such as the female college students who are part of the movement. And coincidentally with the ‘Me Too’ movement, sex scandals have become the focus. Just as the ‘male perpetrator’ stereotype was used to explain Pastor Jung in very simple terms, the male members of Providence have also come under scrutiny. All female members are classified as potential female victims, and their public claims that they are not victims are ignored.”

Lee concurred, evidencing the paradox that considering all female Providence devotees as “victims” “reinforces a patriarchal ideology against female members, allegedly ‘in the name of justice.’”

“Sex scandals are embedded in Taiwan’s social culture,” Li said, and “they are a traditional tool used to attack ‘cults.” In the case of Providence, however, she noted an unprecedented “witch hunt” against members who are not accused of any crime.

Taiwan’s Christian community, Li observed, has not defended Providence but has jumped on the anti-cult bandwagon. “Other Christians think that Providence members just ‘should not’ believe in their church, and the ‘correct behavior’ for them would be to leave Providence and eventually join another church. However, questions of ‘religious truth’ are actually unsolvable and certainly cannot be solved by television series.”

On the one hand, the situation of President Jung and of its followers who are not on trial should be carefully distinguished. On the other hand, there is a risk that the climate of hate created by Netflix and other media would affect both the trial in Korea and how Providence believers are treated in Taiwan and elsewhere.

“In any case, Hung summarized, we advocate for a fair and impartial trial for any individual involved in a court case, and we trust that the legal system will uphold the principles of justice and ensure that the proceedings are not tainted by prejudice or bias. It is our hope that any case will be adjudicated with due process and that the outcome will be based on evidence and the rule of law. As scholars, we remain committed to promoting fairness, justice, and understanding in matters related to religion and the law. We sincerely believe that procedural justice is essential to our society.”