In Shakespeare’s and Verdi’s story, Iago did not kill Desdemona but poisoned the mind of the assassin. Sounds familiar?

by Massimo Introvigne

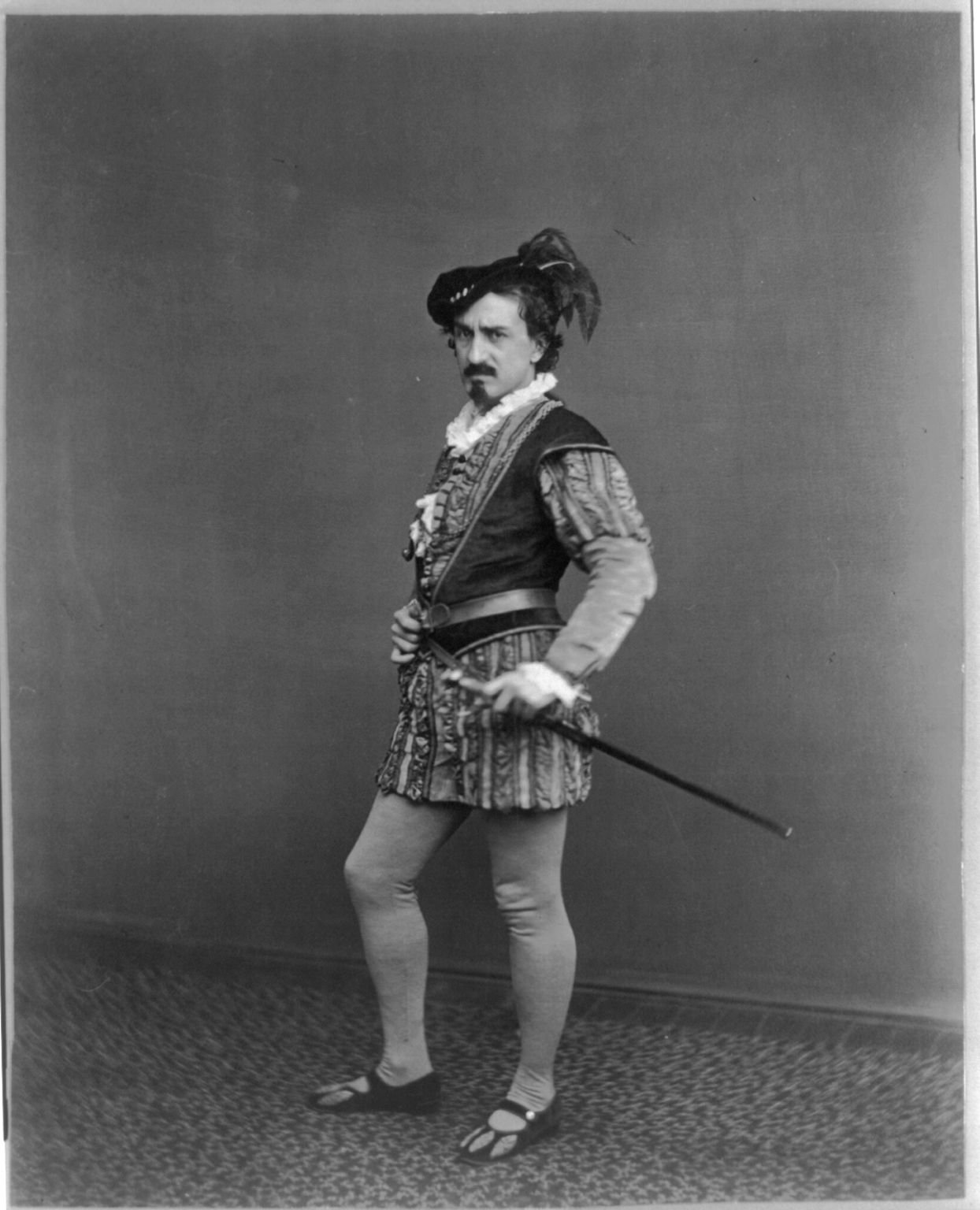

For centuries, philosophers, literary critics, and even legal scholars have wrestled with the character of Iago in Shakespeare’s “Othello,” one of the most famous plays in the whole history of Western literature, first represented in 1604. As an Italian, I first encountered him not on the theatrical stage but in Giuseppe Verdi’s opera, which dates back to 1887 and is frequently performed all over the world.

The story centers on Othello, a victorious African general in the 16th-century army of the Republic of Venice, who is deeply in love with his wife, Desdemona. Iago, an officer serving under Othello, appears to be his friend but secretly harbors envy and plots to destroy him.

In the end, Othello murders Desdemona, after Iago has poisoned his mind with false whispers of infidelity. Shakespeare reassures us that justice will prevail. Iago is apprehended and sentenced, after the authorities become aware that he has personally committed two other homicides, thus making a legal investigation into his guilt in the Desdemona case unnecessary. The play’s moral order remains intact.

Verdi, composing his opera almost three centuries later, is less tidy. In the opera, the two extra murders are not mentioned, and Iago escapes just before Othello’s suicide. No neat resolution, no legal reckoning. Could Iago have been prosecuted for Desdemona’s death? After all, Othello, not Iago, wielded the blade and killed Desdemona. Iago wasn’t even present at the fatal moment. The opera leaves us dangling in ambiguity.

Fast-forward another 150 years, and one imagines Iago filing objections in a modern court. He would protest that he is unjustly slandered, the victim of a SLAPP suit launched by Othello’s friends. He would insist he was quoted out of context, that his musings in his conversations with Othello were purely hypothetical—“if” Desdemona had cheated, perhaps punishment was understandable. He might even point out, as Verdi does, that Othello was already prone to violence. The inclination lay dormant, waiting to be activated.

Dormancy, of course, is a concept that has migrated from opera houses to terrorism studies. Scholars now speak of “dormant” terrorist individuals and cells: with the potential for violence, simmering grievances, and justifications at the ready. They may remain inert for years, even decades, until external triggers awaken them.

Which brings us from 16th-century Cyprus, the setting of the Othello story, to contemporary Japan, and the assassination of Shinzo Abe. Tetsuya Yamagami, Abe’s killer, described himself at trial as precisely such a dormant terrorist. He confessed to a long-standing inclination to violence and mentioned grievances born in 2002 when his mother went bankrupt, allegedly after donating excessively to the Unification Church. Even after the local congregation reimbursed a substantial part of the donation, he said his grievance endured, fossilized in memory.

Two decades later, in 2022, he acted. Why Abe? Yamagami admitted he would have preferred to kill Mother Han, the Korean leader of the Unification Church, but found her too difficult a target. Yet, Japanese church executives, more directly tied to his grievance, circulated freely without bodyguards or bulletproof vests. However, he chose Abe. His explanation—that a routine message Abe sent to a church-linked event in 2021 disturbed him—rings thin. Between 2002 and 2022, dozens of politicians cooperated with the church more visibly than Abe. Why Abe, then? The answer remains elusive, as mysterious as the motives that drive Shakespeare’s characters.

Court testimony offers clues. In July 2022, Yamagami regularly visited Yaya Nikkan Cult News, a site run by anti-cult journalist Eight Suzuki. Nine days before the attack, he sent the site a message of admiration. He testified in court that this was the website from which he primarily derived information about the Unification Church’s political connections. The website had even reported a planned meeting between Abe and Mother Han.

Yamagami testified that learning about these connections triggered a crisis: “If the cult gains social legitimacy through Abe, it will become impossible to stop them.” This concern, he said, shifted his target from church executives to Abe.

Clearly, to argue that anti-Unification-Church journalism killed Abe would be as simplistic as claiming Iago murdered Desdemona. On Japanese social media, many blame Eight Suzuki. But moral panics are never the work of one pen alone. They are choruses—journalists, lawyers, politicians—singing in dissonant harmony, creating resentment against both the Unification Church and Abe as its ally in conservative, anti-Communist causes. What emerged was a collective Iago, poisoning the mind of a Japanese Othello.

And, like Iago, they deny responsibility. They protest that they were quoted out of context, that court cases based on accusations of defamation and hate speech are mere SLAPP suits. Yet where there is an Othello, there are always Iagos. The question is not whether they killed—they didn’t—but how their narratives corroded Yamagami’s thinking. Through what psychological alchemy does a man come to believe that eradicating “absolute evil” is justifiable?

Shakespeare and Verdi whisper the answer: look for the Iagos. They do not wield the knife. They do not pull the trigger. But they create the mental machinery by which violence feels righteous. Without confronting its Iagos, Japan cannot come to terms with the assassination of Shinzo Abe.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.