By singling out one specific religious organization, Sweden has violated European and international human rights law.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 4 of 4. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

In the previous articles of this series, I traced the long and winding road Jehovah’s Witnesses have traveled in Sweden—from their registration as a religious community in 2000, through years of legal battles, to their brief inclusion in the state subsidy system in 2019. This was followed by a legislative overhaul in 2024 and a discriminatory application process that culminated in their exclusion from subsidies in October 2025.

In this final installment, I examine the broader implications of Sweden’s actions and argue that Sweden has violated international and European conventions on religious liberty twice.

The first breach occurred with the passage of Act 2024:487, a law whose intent was not hidden but publicly declared. As mentioned earlier in this series, during a televised interview in 2022, the Minister of Culture stated, “The legislation has clearly not worked here. Therefore, we will also go to the Riksdag with new legislation in this area to correct this.” The target was clearly identified: the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

This sentiment was echoed by Professor Ulf Bjereld, the government’s own investigator, who confirmed that the law was drafted to prevent Jehovah’s Witnesses from receiving subsidies. His comment—“We’ll see if this legislation is sufficient to prevent them from receiving subsidies”—was a declaration of intent to legislate exclusion.

Such statements, coupled with the law’s structure and timing, reveal a deliberate violation of the principle of state neutrality in religious matters, enshrined in both the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The second violation lies in how the law was applied. The Swedish Agency for Support to Faith Communities (SST), now the sole authority under the new law, has a long history of hostility toward Jehovah’s Witnesses. As early as 2008, it issued a negative opinion, quoting sources that had labeled them a “sekt” (cult) and objecting to their beliefs on political neutrality, blood transfusions, and congregational discipline. In 2014, it repeated its objections, using derogatory language and unfounded accusations.

The October 2025 decision continued this pattern. The SST admitted to relying on hostile media reports, claims by anti-cult activists, and testimonies from disgruntled former members. It also disclosed the composition of its review panel—dominated by representatives of religions already approved for subsidies, including priests from the Church of Sweden, an imam, and the former head of the Jewish Community of Stockholm. This raises serious concerns about conflict of interest and institutional bias.

Most damning, the SST acknowledged that it had sent doctrinal questions only to Jehovah’s Witnesses—not to any of the other 45 religious communities applying for subsidies. This selective scrutiny undermines the legitimacy of the entire process and constitutes a form of procedural discrimination.

While Jehovah’s Witnesses were excluded for their views on homosexuality, other religious groups with similar doctrines were not subjected to the same treatment. Consider the Catholic Church, which continues to receive state subsidies in Sweden. Despite recent gestures of compassion and inclusion, its official doctrine remains unchanged. The normative “Catechism of the Catholic Church,” paragraph 2357, states: “Homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered. They are contrary to the natural law. They close the sexual act to the gift of life. They do not proceed from a genuine affective and sexual complementarity. Under no circumstances can they be approved.”

This is not a call to exclude the Catholic Church—doing so would compound injustice. But the difference in treatment is striking. It reveals that the new law is not being applied uniformly, but selectively—targeting Jehovah’s Witnesses while sparing others with comparable beliefs.

At the end of the day, Sweden has come full circle. Once, it granted state subsidies only to the Church of Sweden, the religious embodiment of the prevailing values in Swedish society. Then, recognizing the injustice of this arrangement, it expanded support to other religious communities—an acknowledgment of Sweden’s growing pluralism.

But pluralism means more than diversity of names. It means accepting profoundly different views on issues like sexuality, family, and religious discipline. If only those who conform to the majority’s worldview are deemed eligible for support, then pluralism becomes a facade—a bogus pluralism that rewards conformity and punishes conviction.

By amending its law with the explicit purpose of excluding Jehovah’s Witnesses, and by applying it in a way that reinforces discrimination, Sweden has abandoned its commitment to religious neutrality. It has institutionalized a system where only those who mirror the “Swedish ethos” are deemed worthy of public support.

If Sweden’s higher courts fail to correct this injustice, the matter should be brought before the European Court of Human Rights. The stakes are high—not just for Jehovah’s Witnesses, but for every religious community whose beliefs diverge from the cultural mainstream.

Religious freedom is not the freedom to agree; it is the freedom to disagree. It is the freedom to differ. And in a democracy, that freedom must be protected—not punished.

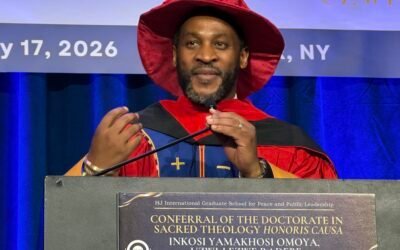

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.