Čiurlionis was a friend and pupil of Polish symbolist painter Kazimierz Stabrowski, a prominent Theosophist, and also read the works of Flammarion, another Theosophist.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

Within the Soviet context, those who wanted to defend Čiurlionis and preserve his works had a vested interest in denying that he had any connection with Theosophy, a movement regarded as bourgeois and reactionary. But we should not forget that even in the West, until things changed in the 21st century, those who wrote about the Theosophical connections of Kandinsky (such as the Finnish scholar Sixten Ringbom, 1935–1992) or Mondrian, were ostracized by an artistic establishment afraid that associating modernistic art with a “cult” may discredit it (and even lower the commercial value of the paintings).

Ringbom’s 1970 “revelation” that Kandinsky had been deeply influenced by Theosophy seriously jeopardized his career, and led to some parts of the Kandinsky archives becoming inaccessible to scholars for decades.

A sympathetic approach to the influence of Theosophy on Čiurlionis emerged in the 1980s with Genovaitė Kazokas (Budreikaitė-Kazokienė, 1924–2015). Kazokas, originally a dentist, studied history of art in Australia and completed in 1982, when she was 58 years old, her M.A. Dissertation on Čiurlionis at the University of Sydney.

She published it in book form only in 2009, when she was 85, thanks to the efforts of Lithuanian pianist Rokas Zubovas, himself a participant in the Druskininkai conference, who is Čiurlionis’ great-grandson and later played the artist in the 2013 movie “Letters to Sofija.”

The Italian scholar Gabriella Di Milia, who married the well-known abstract sculptor Pietro Consagra (1920–2005), was instrumental in introducing Čiurlionis to the West already in the Soviet era. Later, in 2010–2011, she was the curator, together with Osvaldas Daugelis (1955–2020), of the large Čiurlionis exhibition at the Royal Palace in Milan. The title of the exhibition, “Čiurlionis: An Esoteric Journey, 1875–1911,” made immediate reference to the prominence of the esoteric connection in Di Milia’s interpretation.

But not everybody agreed. Among those who downplayed the Theosophical influence on Čiurlionis was the distinguished Lithuanian art historian Rasute Andriušytė-Žukienė. She argued that “neither the popular fascination with the East, nor the enticements of esotericism which appealed to many artists of the time, succeeded in impelling Čiurlionis to deeper and more committed study of any one philosophical trend or religion, let alone its practice.”

Polish scholars interested in the occult circles around the Warsaw School of Fine Arts, where Čiurlionis studied, also emphasized how he was introduced there to Theosophy (Karolina Maria Hess and Małgorzata Alicja Biały [Dulska]) and the esoteric and mystical ideas of Juliusz Słowacki (1809–1849: Radoslaw Okulicz-Kozaryn).

![Karolina Maria Hess and Małgorzata Alicja Biały [Dulska].](https://bitterwinter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Karolina-Maria-Hess-and-Malgorzata-Alicja-Bialy.jpeg)

![Karolina Maria Hess and Małgorzata Alicja Biały [Dulska].](https://bitterwinter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Karolina-Maria-Hess-and-Malgorzata-Alicja-Bialy.jpeg)

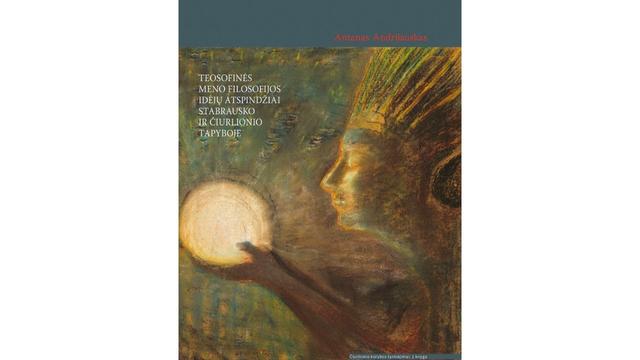

In recent years, several Lithuanian scholars returned to the issue of Theosophical influences on Čiurlionis. A comprehensive treatment of the issue was offered in 2021 in a book by Antanas Andrijauskas, who had already written several important articles, and concluded that, while Čiurlionis was never a member of the Theosophical Society, Theosophy and other esoteric currents had a significant influence on him.

We can study the question of Čiurlionis’ relationship with Theosophy in two ways: historically, by reconstructing certain influences and connections in the artist’s life, and iconographically, by examining the themes and symbols in his paintings. The second path is, however, much more uncertain than the first.

In 1904, Čiurlionis enrolled in the newly established Warsaw School of Fine Arts. Its director was Kazimierz Stabrowski (Kazimieras Stabrauskas, 1869–1929). Stabrowski was only six year older than Čiurlionis. The two became friends, and Čiurlionis credited Stabrowski for making him a professional painter.

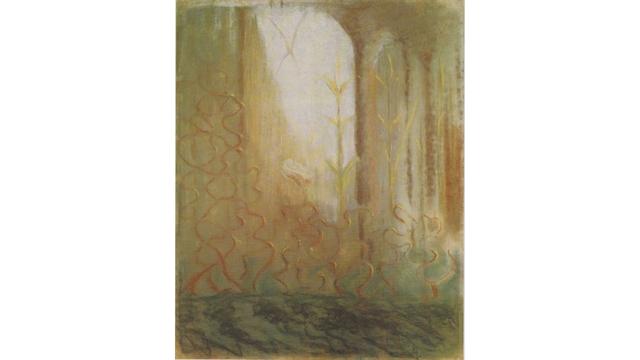

Like Čiurlionis , Stabrowski was influenced by Lithuanian folklore, which he combined with symbolism in what is perhaps his most famous painting, “Stained Glass Background: A Peacock,” a Klimtian portrait of his student Zofia Borucińska (née Jakimowicz, 1883–1969) during a Mardi Gras ball.

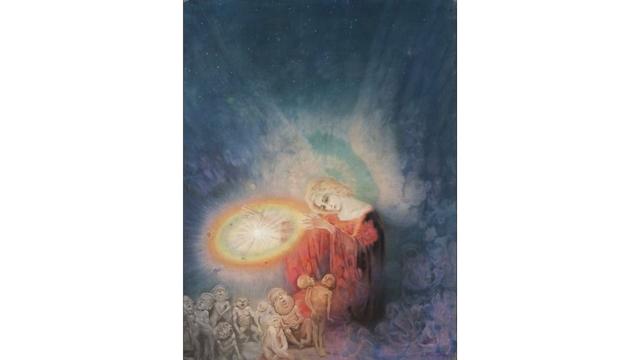

Stabrowski was a Theosophist and several of its paintings, such as “The Consoler of Monsters” have a clear Theosophical flavor. He joined the Theosophical Society in 1907 but, as Andrijauskas and Karolina Maria Hess have demonstrated, his interests for Theosophy and Spiritualism date back to his youth and were well developed before he met Čiurlionis.

In 1920, Stabrowski will be among the founders of the Polish Theosophical Society, and later moved to Anthroposophy, but this was long after Čiurlionis’ death. During his years at the Warsaw School, Stabrowski and his wife organized and Čiurlionis participated in the so-called “wild strawberry tea parties,” which were not formal meetings of a Theosophical lodge but included discussions of Theosophy, oriental religions, Spiritualism, and parapsychology.

In 1909 Stabrowski lost his position at the Warsaw School due to poor financial management but also because of controversies connected with his involvement of students in Spiritualist seances. Some of them were in the house of poet Edward Słoński (1872–1926) and featured the famous Polish Spiritualist medium, Jan Guzik (1875–1928), but Čiurlionis himself occasionally served as a medium in the wild strawberry tea parties.

At the parties, Čiurlionis met several artists and intellectuals (including those from the “Young Poland” circle) who fueled his interest in Oriental religious traditions, Theosophy, and parapsychology (and, as Vida Mazrimienė reports, might have put him in touch with books published by the Theosophical Society). One who eventually joined the Theosophical Society, and whose influence on Čiurlionis has been noted by Andrijauskas, was esoteric poet and playwright Tadeusz Miciński (1873–1918). Another was Indologist Stanisław Franciszek Michalski (1881–1961), a college student at that time but, according to Hess, already in a position to pass to Čiurlionis first-hand information on Hinduism and Buddhism.

Boris Leman already reported that at Stabrowski’s the Lithuanian artist was more interested in reincarnation and hypnotism than in Spiritualism. This was confirmed by Čiurlionis’ sister Jadvyga (1899–1992), who reported he even hypnotized the parish priest of Druskininkai, and brother Stasys (1887–1944)—although Jadvyga downplayed these aspects in Soviet times.

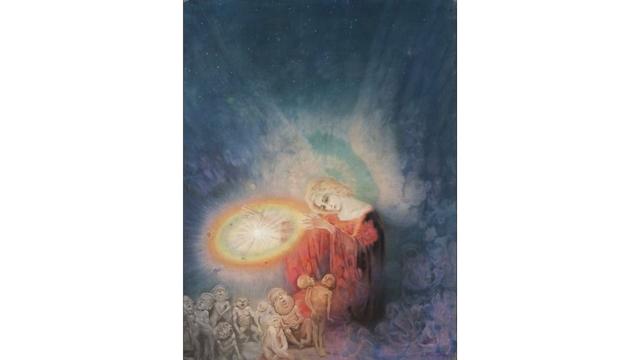

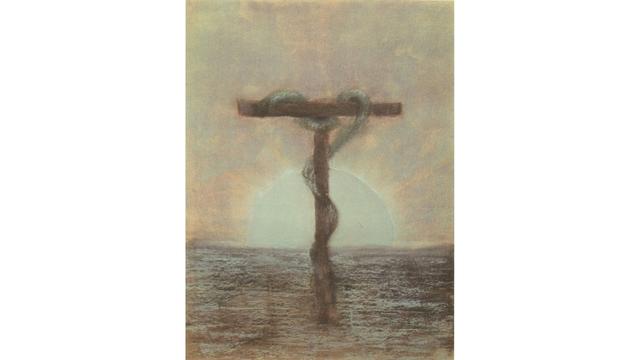

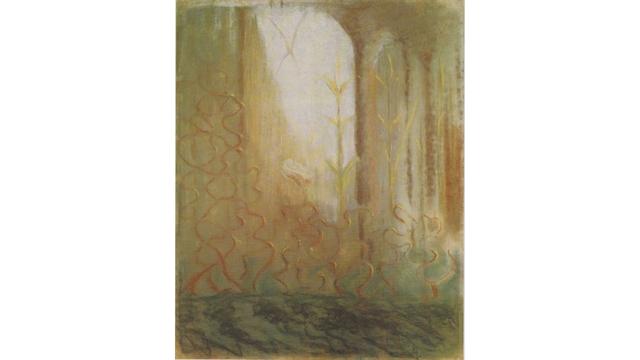

In 1905, Čiurlionis exhibited at Stabrowski’s School, amongst nine other paintings of a series called “Fantasy,” a work called “Vision” featuring a serpent on a Cross of Tau (which is also the letter T for “Theosophy” in Theosophical iconography).

The painting was very much discussed at the Druskininkai conference (see the first article of this series). It evidences the painter’s early fascination with the theme of the serpents, which had both Theosophical, ancient Lithuanian, and Biblical sources.

In two other paintings of the 1905 exhibition, “Composition” and “The World of Mars,” critics have seen the influence of French astronomer and leading Theosophist Camille Flammarion (1842–1925).

The “Mars” painting seems indeed indebted to Flammarion’s book on that planet, and we know from Čiurlionis’ correspondence that he did read the works of Flammarion. It would not make sense to contrast the influence on Flammarion and of Theosophy on Čiurlionis, as Flammarion was himself a leader of the Theosophical Society and his books have clear Theosophical references.

A later Theosophical connection might have been the international project around the character of Prometheus devised by two Theosophists, Belgian painter Jean Delville (1867–1953) and Russian composer Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915). They planned to recruit Čiurlionis, together with Russian sculptor Seraphim Sudbinin (1867–1944) and Swiss sculptor and medalist Auguste de Niederhäusern, better known as Rodo (1863–1913). However, when reached by Scriabin’s invitation in 1909, Čiurlionis, already plagued by poverty and poor health, did not answer.