Through its Celebrity Centres, Scientology systematically interacts with the artists, be they superstars or “commercial” painters.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 7 of 8. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, article 4, article 5, and article 6.

Among modern new religious movements, Scientology is unique for its conscious effort of transmitting its worldview to the artists, at the same time teaching them how to be more apt at communicating their art to their audiences, through its courses and seminaries taught in its Celebrity Centres. Yet, Scientology’s influence on artists is understudied. One of the reasons lies in the attacks and discrimination some artists have received because of their association with Scientology, particularly in Germany.

There, abstract painter and textile artist Bia Wunderer is one of the artists who had exhibitions cancelled because she was “exposed” as a Scientologist (here, as elsewhere in this part of the series, I rely on personal interviews rather than on written sources). This made some artists understandably reluctant to discuss their relationship with Scientology. However, in Germany, of all places, artists were involved in Scientology since its beginnings. When he died in 2015, painter and sculptor Waki Zöllner (1935– 2015), who had joined Scientology in 1968, was the German with more years of Scientology training.

While there is a significant literature on artistic superstars who are Scientologists, I will focus here on artists whose connection with Scientology has been studied less often. Scientology through its Celebrity Centres also created a community of artists, knowing and meeting each other across different countries, continents, and styles. Several Scientologist artists decided to live either in Los Angeles or in Clearwater, Florida, near the main centers of the Church of Scientology.

Scientologist artists do not share a single style, as is true for artists who are Theosophists or Catholics. For example, German-born Carl-W. Röhrig (b. 1953), currently residing in Switzerland, calls his art “fantastic realism” and is also influenced by fantasy literature, surrealism, and popular esotericism, as evidenced by his successful deck of tarot cards. There are, however, common themes among Scientology artists, as evidenced in interviews I conducted with a number of them (the subsequent quotes, unless otherwise indicated, are from those interviews).

Röhrig is among the few Scientologist artists who included explicit references to Scientology doctrines in some of his paintings, including “The Bridge,” i.e. the journey to become free from the effects of the reactive mind. Röhrig and other artists who are Scientologists, including the American Pomm Hepner and Randy South (aka Carl Randolph), also contributed murals to churches of Scientology around the world. California Scientologist artist Barry Shereshevsky devoted several paintings to the ARC triangle.

California sculptor D. Yoshikawa Wright moved “from Western to more Eastern thought,” rediscovering his roots, and finally found in Scientology something that, he says, “merges East and West.” About his “Sculptural Waterfalls,” he comments that the stone represents the thetan, the water the physical universe as motion, and their relationship the rhythm, the dance of life.

Another Scientologist sculptor (and painter), the Italian Eugenio Galli, experiments with rhythm and motion through different abstract compositions all connected with the idea of “transcendence,” i.e. transcending our present, limited status.

Artists who went through Scientology’s Art Course all insisted on art as communication. Winnipeg-born New York abstract artist Beatrice Findlay told me that “art is communication, why the heck would you do it otherwise?” She also insisted that Hubbard “never said abstract art communicated less” and had a deep appreciation of music, a form of abstract communication par excellence. Hubbard’s ideas about composition are translated by Findlay into peculiar abstract lines and color.

At least the name of another Canadian abstract artist who was once a Scientologist, Richard Borthwick Gorman (1935–2010), should be mentioned here, since recently anti-Scientologists, in a bizarre development, claimed that his 1968 new covers for some of Hubbard’s books carried subliminal messages and were an attempt at brainwashing those who would look at the covers.

Other Scientologist artists apply the same principles to a more traditional approach to landscape. They include the Italian Franco Farina, the Canadian Ross Munro, and the American Erin Hanson, whose depictions of national parks and other iconic American landscapes in a style she calls “Open Impressionism” won critical acclaim.

Pomm Hepner is both a professional artist and a senior technical supervisor at Scientology’s church in Pasadena, as well as a leader in Artists for Human Rights, an advocacy organization started by Scientologists. As Scientology taught her “on the spiritual world,” she evolved, she says, from “pretty things” to “vibrations,” from “a moment that exists to a moment I create… I can bring beauty to the world and no longer need to depend on the world bringing beauty to me.”

By adopting the point of view of the thetan, she tried to “reverse” the relationship between the artist and the physical universe. A similar experience emerges in the artistic and literary career of Scientologist Renée Duke (1927–2011). Although she had painted before, she became a professional painter only later in life, after she had encountered Scientology.

There is a difference between how Scientologist artists were discriminated against in Europe and some mild hostility their beliefs received occasionally in the U.S. However, they all stated in my interviews that modern society is often disturbed by artists and tries to suppress them, singling out psychiatry as a main culprit, a recurring theme in Scientology. “The Trick Cyclist” by Randolph South depicts well-known psychiatrists and “was created to draw attention to the evil practice of psychiatry.”

The youngest child of L. Ron Hubbard, Arthur Conway Hubbard (b. 1958), himself became a painter and in some of his paintings he used his own blood.

Pollution as a form of global suppression and Scientology’s mission to put an end to it are a main theme for Röhrig. Landscapes and cultures in developing countries are also in danger of being suppressed. This is a key subject in the work of Swiss Scientologist artist Claude Sandoz, who spends part of his time in the Caribbean, in Saint Lucia. Exhibitions of Sandoz’s works, which blends Caribbean and European themes and styles, took place in several Swiss and international museums.

Some of those who took Scientology’s Art Course are “commercial” artists. The course told them that this is not a shame and hailed success as healthy. They believe that the boundary between commercial and fine art is not clear-cut. Some of them were encouraged to also engage in fine arts. Veteran Scientologist artist Peter Green, who also produced one of the most famous portraits of Hubbard, claims he understood through Scientology that commercial artists are not “coin- operated artists,” but have their own way of communicating and presenting a message. Green manifested this approach in his iconic posters, such as a famous one of Jimi Hendrix (1942–1970).

Green also contributed to horror comics magazines published by the Warren company in California, and kept producing his successful Politicards, i.e. trading and playing cards with politicians. He insists that you can “paint to live and remain sane. And in the end, you may live to paint too.” Randy South insisted that, even when working for advertising, artists may “perceive the physical universe” as “not overwhelming spirituality” but “vice versa.” He added that “Hubbard said that life is a game. I want to play the game, and it’s fun.”

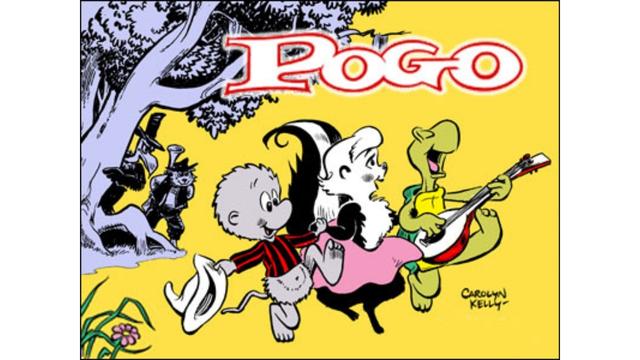

The portraits of another Scientologist artist, Robert Schoeller, are sold for commercial purposes, but he believes that “by painting somebody I make him spiritual.” In fact, there have been museum exhibitions of his portraits around the central theme of spirituality. Similar considerations may be made about an Italian portrait artist, Domenico Mileto, and for Jim Warren’s popular lithographs and Disney-related themes. Other Scientologist artists became photographers and cartoonists. Carolyn Kelly (1945–2017) was the daughter of well-known American cartoonist Walt Kelly (1913–1973), the creator of Pogo. She was a cartoonist and illustrator in her own right, and was among those who designed her father’s Pogo when the strip was shortly revived in the 1990s.