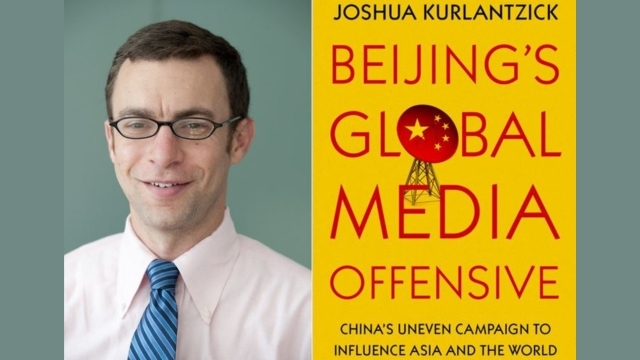

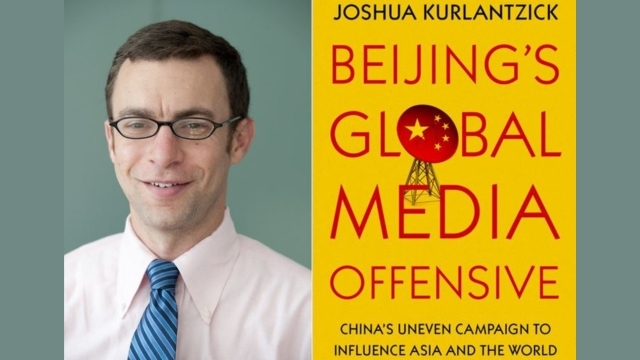

The level of the CCP’s media control throughout the world is already immense. It may become worse, says Joshua Kurlantzick in a new book.

by Marco Respinti

Table of Contents

Over the last decade or so, the neo-post-nationalist-communist regime of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) became also neo-colonial. Hints to forms of racism are here intentional, based on the cultural genocides that the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is waging on against many peoples living in the PRC’s territories. PRC’s is neo-colonialism 2.0, and its strategy works through communication and media, chiefly the Internet. But media as a means for colonization ought to be first colonized themselves.

It is what has been called China’s “Digital Silk Road” (DSR). Launched in 2015, it is a component (or a spin-off, as it has been said) of the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), a.k.a. one of the arms of the CCP’s imperialistic approach to rethinking and rewriting globalization (or what remains of it).

The PRC proudly lays claim to its alive and kicking Communist identity in an age of predominant technological power. Since the historical failure of Communism in the world has compelled the PRC (as other proudly Communist regimes) to partially reshape its tactics (not its goals), the name of this projected new globalization CCP-style could well be “technocratic socialism.” Or, taking the CCP’s massive and strategic colonization of media into account, “techno-mediatic socialism.”

Beijing’s communication offensive

Substantially, DSR is a concerted effort to control the flow of information globally, using powerful tools to expand China’s influence in regions far beyond its own borders. The US think tank Council on Foreign Relations, which closely watches DSR since its inception, notes that “some democracies have raised serious concerns about the Digital Silk Road. They worry that, at a time when Beijing is becoming more assertive on the global stage, China will use the DSR to enable recipient countries to adopt its model of technology-enabled authoritarianism, which would be detrimental to personal freedoms and sovereignty in those countries. Chinese technology companies have already helped governments in other countries develop surveillance capabilities that could be used against opposition groups, and Beijing has provided training for interested DSR recipient countries on how to monitor and censor the internet in real time.”

Furtherly, the CFR warns, “allowing Chinese firms to build countries’ fifth-generation (5G) networks and other infrastructure, and to set technology standards that could become the norm in many countries, could risk espionage and coercion of other states’ politics if Beijing used data breaches to blackmail political elites in those states. The DSR could also help recipient countries better control their internets through filtering, content moderation, data localization, and surveillance. Doing so would accelerate a fracturing of the global internet, as some countries pursue these policies of internet control while others remain committed to internet freedoms.”

Now, PRC’s control of information passes through a spectacular technological infrastructure that seems to virtually make everything possible for the CCP leaders in Beijing. The plan of action involves expanding state-run media outlets, such as the state press agency Xinhua, and positioning them as credible alternatives to established news agencies based in democratic countries that may be critical of the PRC’s propaganda. As “Bitter Winter” documented several times, Italy remains a case study of international relevance since it is the European country where the Chinese propaganda war and colonization of media started earlier, and it became massive and systematic. But the threat is global.

Joshua Kurlantzick’s recent comprehensive and detailed book “Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World” (New York: Oxford University Press, December 2022— which the author effectively summarized in a substantial article for the specialized international online news magazine “The Diplomat” —provides the most updated picture of the state of the art and much useful information. An American journalist, Kurlantzick is a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the CFR.

As he documents, the Chinese regime began using proxies to control Chinese-language media outlets abroad and became increasingly skilled at deploying disinformation on social media platforms, both domestically and internationally.

The CCP-led PRC also seeks to control what Kurlantzick calls the “pipes” that underpin communication and information networks, including physical telecommunications infrastructures, mobile devices, the “Internet of Things” tools, commonly known as “IoT,” (“smart environment,” “smart agriculture,” “smart logistics,” “smart lifecycle,” “smart retail,” “smart health,” etc.) as well as leading search engines and social media platforms, possibly even AI technology.

The hardship of China’s soft power

It is customary to call this type of influence “soft power,” but it is quite the contrary. Soft may be the approach, but hard is the force implied. Kurlantzick reveals the true face of this not-so-soft PRC’s exercise of power and its capacity of depriving the world of independent coverage about its misdeeds.

At an international level, Beijing’s power and hold of media aims at a double goal. First, “[i]f Beijing had more control of the pipes of information, it also could, within foreign countries, more easily censor negative stories and social media conversations and spread stories, rumors, opinions, accusations, blandishments, and other types of disinformation, obviously types of sharp power.” Second, Beijing “could use the pipes to help foreign countries copy China’s surveillance strategies and to export China’s model for a closed and controlled domestic internet, part of Beijing’s overall model of technology-enabled authoritarianism.”

That Internet, starting from its Chinese domestic edition, is of course an essential aspect of Beijing’s “techno-mediatic socialist” offensive emerges even from the 50th “Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development,” released on August 1, 2022, by China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), or the governmental administrative agency responsible for domain registry affairs in the country.

We in fact live in times where unchecked news are available on devices that people effortlessly carry in their pockets. Sometimes, self-styled “professional fact-checkers” are mere amplifiers of might-is-right players in communication. As for the general users of the Internet, even the most serious debunkers of forgeries may fail to persuade them. The Internet is in fact often perceived as an immaculate realm. A lie repeated many times, while of course remaining a lie, may be credited as truth by virtue of its repetition.

In the hands of the CCP and the PRC, this becomes a powerful weapon to both impose at home and try to export abroad a closed and controlled access to information. Outside China, it feeds the myth of the effective, if not benevolent, “Chinese model” that seems to gain consensus even within certain intellectual circles in democratic countries. They are happy to trade liberty for more alleged security. In the case of the Internet, this mentality may well flourish rapidly thanks to a subtle scheme. First, the fabrication and widespread diffusion of fake news on the Internet (where they circulate more easily than on other information pipes) undermine credibility and advance the case for post-truth. Second, once post-truth is established at a sufficient level, restrictions are invoked claiming they are needed to contain fake news, while they instead deny truth at a deeper level, and serve as a justification for controlling media in a way that in the end many would regard as acceptable.

Control the Internet, control the world

This irregular, asymmetric, and dirty war is fought globally by the CCP also thanks to a vast army of accidental soldiers. China remains in fact the country with the largest population on the Internet in the world, with a fast-growing mobile app market. It projects a steadily increasing growth in number of users for the next few years, at a time when most of the world population obtain information and news (and possibly even its cultural, political, and economic education) from the Internet. They believe that the Internet is the realm of unchecked liberty, while it may paradoxically become more and more dominated by a country that restricts access and controls contents.

Intermittently on the Internet since May 1989, China is there on a permanent basis since April 20, 1994. The first project of massive surveillance and content control of the virtual net dates from the previous year, 1993, and was advanced by the then Premier of the PRC’s State Council, or the head of the government, Zhu Rongji, under the name “Golden Shield Project .” In November 2000 it was relaunched full-style and became entirely operative as the “Great Firewall of China,” or the most extensive and ultra-modern censorship program of the Internet in the world.

Of course, the effect exerted on information by an Internet content production system that is the mouthpiece of what is virtually the most developed and capillary industry of fake news on the globe is similar to an atomic bomb blast. And Beijing’s holding of a dominant portions on some foreign country’s mobile infrastructures is the key to this control.

In many countries, Kurlantzick writes in his book, Chinese state firms have partnered “with local tycoons currently in favor with government leaders” and “often are able to land contracts to build mobile and fixed internet infrastructure, sometimes without any transparent bidding processes.”

The most evident case of how the CCP’s DSR initiative works is Africa. Chinese companies receive loans from Chinese banks on extremely easy terms, allowing them to build telecommunications infrastructure abroad, while non-Chinese competitors face serious obstacles in obtaining the same level of diplomatic support from the governments of their respective countries or the friendly financing conditions that Chinese companies enjoy.

Colonialism: it always starts from Africa

In Africa, Kurlantzick notes, Beijing “has become by far the dominant builder of new physical infrastructures to transmit information.” Kurlantzick underlines the role of the Chinese state-owned company China Telecommunications Corporation, known as China Telecom, and ZTE, the partially state-owned technology company specialized in telecommunication that faced criticism for its involvement in the PRC’s mass surveillance, and in June 2020 was designated as a national security threat by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). China Telecom and ZTE “are building the core of new mobile and fiber-optic networks across Africa, competing largely with Huawei,” another much-criticized usual suspect that in November 2022 the FCC similarly banned from trade for national security reasons. Being “a private Chinese company” with “historic links to the People’s Liberation Army,” Huawei is an exemplary case. The Chinese regime’s cunning communication policy of conquest involves in fact also Chinese companies that “are not state firms,” Kurlantzick explains. While these private subjects serve to display a feigned as well as useful pluralism to the world, they invariably “rely on funding from Chinese state banks and China’s sovereign wealth fund,” and “have boards packed with top” CCP’s officials.

Moreover, Kurlantzick adds, Huawei is ready to be the dominant 5G, or “the Internet of the future,” provider in sub-Saharan Africa, virtually with no competitors, while it has contacts to develop it also in Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and possibly Indonesia. As to Southeast Asia, the firm has already built many of the shorter undersea cables that tie telecommunications networks of the area, reaching as far as Oceania, where Huawei and other Chinese tech giants have competed aggressively with Australian and other companies to make new deals in places like Fiji.

A punctual example of the PRC’s media outreach are the Philippines. Dito Telecommunity Corporation (formerly known as Mindanao Islamic Telephone Company, Inc. or Mislatel) is a Filipino consortium that is rapidly enlarging its share of the country’s telecommunication market. 40% of Dito is today owned by China Telecom. And the Philippines are also an example of the efficacy of the alliances that Chinese state firms are able to create with local tycoons.

In the meantime, Huawei already became the dominant provider of 5G in Central Asia too, including countries like Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, which are among the comparatively more liberal states of the region.

Yes, the level of control exerted by Beijing over information and communication is already immense. The CCP can manipulate any flux of news. But it can become worse, since manipulation may be instrumental to extend the CCP’s surveillance on a global scale, threatening liberty, security, and human rights all over the world.