The CCP’s mammoth plan to eradicate banned religious organizations from rural areas is based on false Marxist premises and an outmoded sociology.

by Massimo Introvigne

The China Anti-Xie-Jiao Association published a long comment on a document by the Jiange County Anti-Xie-Jiao Association in Sichuan province, prepared in co-operation with the Jiange County CCP Committee. The comment goes beyond the local problems, and presents the new concept of “rural anti-xie-jiao poverty alleviation” (村反邪教扶贫), which is based on speeches by Xi Jinping himself.

As usual, CCP English-language documents translate “村反邪教扶贫” as “rural anti-cult poverty alleviation.” As readers of Bitter Winter know, translating “xie jiao” as “cult” is largely a political operation, as “xie jiao” has been used in China since the Middle Ages to designate “heterodox teachings” or religious groups regarded as hostile by the government.

The document is written in a heavy CCP jargon, but it has two key aspects. First, it opens a window on the mammoth Chinese anti-xie-jiao organization. It cannot be compared with the anti-cult movements in other countries, not even in France where they are supported by taxpayers’ money and coordinated by a governmental anti-cult agency called MIVILUDES. We learn that in Sichuan’s Jiange County the goal of having a branch of the China Anti-Xie-Jiao Association in each village, including small villages in “remote mountainous areas,” has been reached.

There are also anti-xie-jiao cells in most “government institutions, factories and mines, schools, townships and village committees.” The comment implies that this is not a unique Sichuan situation, although Jiange county may be mentioned as a best practices model, but corresponds to a nation-wide project. This means that, in addition to thousands of Public Security agents devoted full-time to anti-xie-jiao work, there are tens and possibly hundreds of thousands of anti-xie-jiao propaganda activists targeting all neighborhoods, villages, workplaces, and schools.

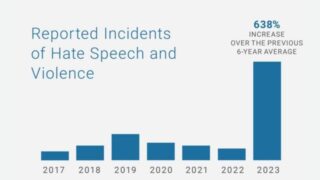

The second aspect is that this mammoth machine, fully backed by the force of China’s equally huge police and judicial system, does not achieve the expected results. Hence the frequent arrests of bureaucrats at the top level of the anti-xie-jiao struggle, accused of corruption but in fact punished for their ineffectiveness, the continuous calls to increase the already enormous number of full time anti-xie-jiao police and activists, and the quest for new formulas, such as the “anti-xie-jiao poverty alleviation.”

In fact, the new formula in itself explains the shortcomings of the CCP’s fight against the xie jiao. It is premised on the idea that Chinese join the xie jiao because they are poor. We read that the poor who suffer in the present life are more inclined to believe that there is an afterlife where they will be happy. Hence, the best way to eradicate the xie jiao is to eradicate poverty, and to give some money to the xie jiao devotees who promise to leave them.

The problem with this strategy is that it is based on a sociology of at least sixty years ago, with roots in 19th-century Marxism. The economic deprivation theory, according to which the poor convert to new religions because they compensate with heavenly hopes or dreams of a future earthly Millennium their present suffering and desperation derives from Marx’s idea of religion as the opiate of the proletarians. It was debunked in the 1970s by David Aberle and by James A. Beckford in his landmark study of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Countless studies have demonstrated that groups labeled by their opponents as “cults” are also joined by those who are not poor.

Some scholars had replaced economic deprivation with “relative deprivation,” arguing that those who convert to new religious movements lack something but this “something” is not necessarily money: it can be peace of mind, happiness, or a purpose in life. This explains why many rich join new religions: they may have everything except peace and happiness. However, Beckford warned that “relative deprivation” often emerges post factum, in the explanations devotees offer after their conversion. They did not know they suffered of a “deprivation” before converting, and discovering that they were in a situation of “relative deprivation” was in itself part of the conversion process.

The CCP may dismiss Western scholars of new religious movements as “cult apologists,” but it does so at its peril. I remember when I still accepted invitations to visit China and interact with local anti-xie-jiao scholars and bureaucrats, their insistence that most members of The Church of Almighty God (CAG) were semi-illiterate rural poor.

My and other Western scholars’ objections that many CAG members who arrived abroad as refugees spoke English and played Western musical instruments with considerable skills, hardly features of illiterate rural poor, were met with disbelief. Marxist theory and CCP documents maintained that those who convert to new religions are poor and uneducated, and empirical evidence was regarded as less important than ideology.

However, a wrong sociology leads to a wrong policy. The false belief that poverty causes people to turn to religion, and eradicating poverty will eradicate religion, is the root cause of the lack of success of the CCP campaigns against the xie jiao and religion in general. Arresting bureaucrats or multiplying the already huge number of anti-xie-jiao activists would not solve the problem.