It is not the first time the French President shows a dangerous tolerance of dictators and a bizarre disregard for freedom of religion or belief.

by Marco Respinti

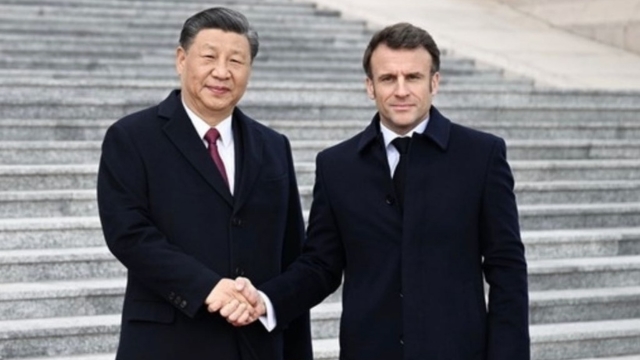

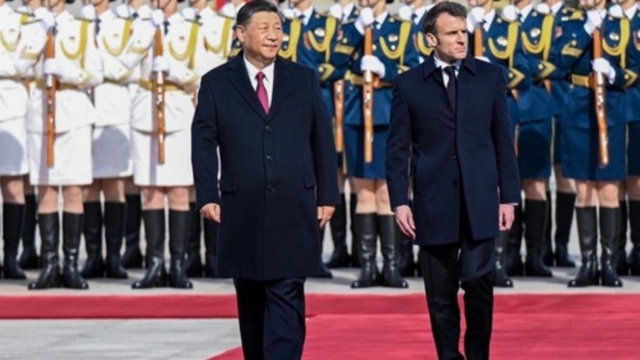

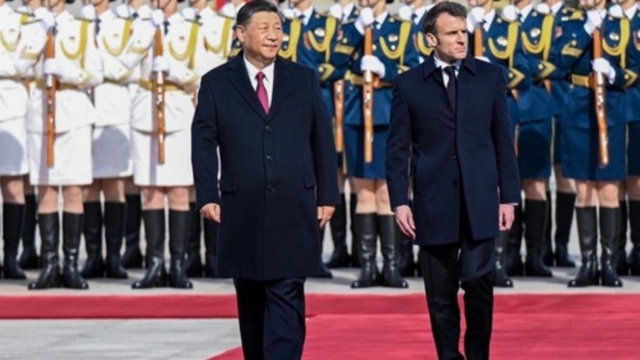

The President of France, Emmanuel Macron, summarized his three-day state visit to the People’s Republic of China and meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in an interview given aboard Cotam Unité (the French equivalent of Air Force One), which was published by Politico.com on April 9, 2023.

“Bitter Winter” covers freedom of religion or belief and human rights, understanding the former as the first of the latter. It does not directly deal with politics. So, “Bitter Winter” is not interested in President Macron’s comment that Europe must reduce its dependency on the United States and avoid getting dragged into a confrontation between China and the U.S. over Taiwan. Also Macron’s emphasis on his theory of “strategic autonomy” for Europe, presumably led by France, to become a “third superpower” does not interest “Bitter Winter,” although it may easily lead to some humorous comments.

We repeat it, we deal with human rights and freedom of religion or belief. Unfortunately, President Macron’s attitudes and words put both and risk, and not for the first time. Let’s start with Taiwan. I happened to be in Taiwan to attend an international religious liberty forum while the PRC showed its military muscles to Taiwan and the world in retaliation to Taiwanese President Tsai’s visit to California.

Macron’s words caused widespread concern and sadness. They also directly concern human rights. As the example of Hong Kong shows, if China will invade and conquer Taiwan, human rights and religious liberty will quickly disappear. Arbitrary arrests, detention, torture, “disappearance” and extra-judicial killing of independent journalists, pro-democracy activists, and religious leaders who do not accept to become puppets of the CCP will follow. This is not speculation. It is what is actually happening in Hong Kong.

The language used by Macron seemed to stigmatize what has been called the American “world cop” policy for the world. His criticism affirms that neither a country, namely the US, nor the international community can play the role of the police officer throughout the world, punishing evil-doers and rewarding good-doers. The underlying idea is that no one is entitled to detect good and evil in international politics, chiefly because in international politics good and evil are not absolute, but relative to interest and convenience.

Unfortunately, Macron is wrong. Good and evil exist also in international politics and should dictate the foreign policy of every freedom-loving country and of the international institutions. There are countries which do not follow these criteria. One is the PRC, the country of harassments, repression, violence, torture, and killings. It deserves to be condemned and isolated, not appeased and praised. Macron seemed very interested in business in his Chinese trip, while he did not mention Chinese violations of human rights, what the French Parliament itself has called a genocide in East Turkestan (Ch. Xinjiang), the oppression of Tibet and Southern Mongolia, and the increased crackdown on religious liberty.

This is not a problem with China only. The web site of the Élysée, the official residence of the French President, or where Macron dwells, which symbolizes the entirety and fulness of the political power of the country, features “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” that France passed in 1789 as the core of its revolution to change the whole world.

There is also an English translation that is virtually official. As the web site reminds, its passing in 1789 “marked the beginning of a new political era. Since then, it has never ceased to be a reference text. The Fifth Republic,” or the present one, of which Macron is the head, “explicitly states its attachment to it, citing it in the preamble of its Constitution, and the Constitutional Council recognized its constitutional value in 1971.”

Article 1 of the Declaration states: “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on considerations of the common good.” Art. 2 says: “The aim of every political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of Man. These rights are Liberty, Property, Safety and Resistance to Oppression.” And Art. 10 proclaims: “No one may be disturbed on account of his opinions, even religious ones, as long as the manifestation of such opinions does not interfere with the established Law and Order.”

These articles should oblige France, of which Macron is the current President, to prevent any assault on women’s and men’s basic rights, liberties, and opinions. These principles should inspire both French domestic policy and their international relations. They don’t.

Without even discussing some ambiguity in Macron’s reactions to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, “Bitter Winter” has noted that a group of Ukrainian scholars, including virtually all tenured professor of religious studies in Ukraine, wrote twice to Macron pointing out that France finances FECRIS, the umbrella organization of European association against “cults,” and that FECRIS includes a Russian branch that has among its main activities supporting the “special military operation” and has slandered Ukraine and its government since 2004, falsely presenting it as a “puppet of the cults.”

Macron never answered, and France in international conferences stated that it will continue to finance and support FECRIS. The same FECRIS, and French anti-cult organizations also supported by the French government, have also cooperated with China in its bloody suppression of Falun Gong, The Church of Almighty God, and other persecuted religious movements.

Macron has a problem with human rights and freedom of religion or belief, and it is an old French problem. On March 31 a newspaper that can hardly be accused of being anti-French, “Le Monde,” published a long article discussing “the French exceptionalism in the field of religious liberty.” Because of the anti-religious heritage of the French Revolution, France has an attitude of suspicion towards religion that is unique in Europe. “Le Monde” reminded its readers that, with all its emphasis on being the mother country of human rights, France waited more than twenty years before ratifying the 1953 European Convention of Human Rights. It did only in 1974.

The reason of this delay, “Le Monde” notes, was that France was reluctant to ratify the article on freedom of religion or belief, because it protects the communal rights of religious organizations, while in the post-1789 French legal tradition freedom of belief is a right granted by the state to individuals, not to communities. The article noted that in recent years, French problems with religious liberty have continued with laws and regulations against the “cults” (“sectes” in French), religious “separatism,” the Islamic veil, and the presence of crosses or Nativity scenes in public spaces.

Macron’s strange acquiescence to totalitarian regimes and bracketing of human rights, particularly religious liberty, has been explained by referring to its roots in the world of business rather than politics, which makes him more sensitive to opportunities for French companies to do business with Russia or China than to moral issues. However, when it comes to religion and belief, there are French historical peculiarities that may also explain Macron’s attitudes.