Casting doubt on the dominant narrative about “the evil Unification Church” is becoming impossible in most Japanese media.

a review by Bitter Winter

Article 4 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

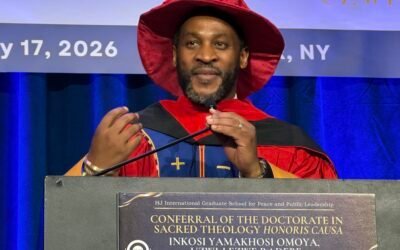

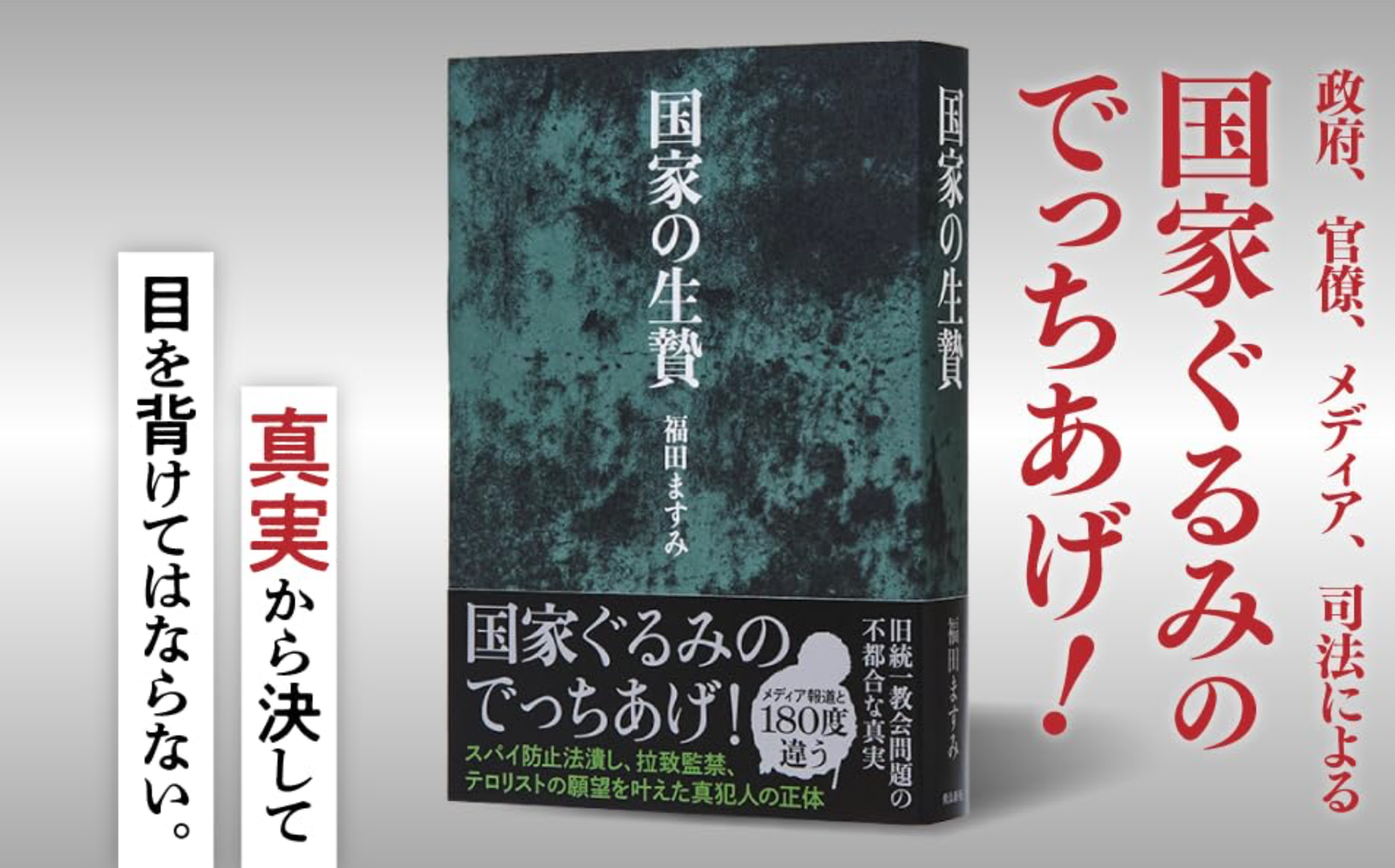

Our series on Masumi Fukuda’s Japanese bestseller “Sacrifice to the Nation” continues, exploring how a democratic society that values constitutional freedoms slipped into a situation in which specific facts could no longer be openly discussed. In the part we discuss today, Fukuda examines the media, the courts, and the Public Security Police. She shows how pressure, bias, and political convenience came together to create a series of distorted stories and unfair decisions.

In Chapter 8, Fukuda reveals the quiet yet strong suppression of free speech by the MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology).

Fukuda starts with a troubling point: in today’s Japan, reporting anything even slightly supportive of the Family Federation, or acknowledging the suffering of its members due to abductions and confinement, has become nearly taboo. She argues that the media is flooded with narratives that flip the roles of victim and perpetrator, particularly after former Prime Minister Abe was assassinated.

This distortion stems from what Fukuda calls an “invisible press code.” Although it isn’t written down, everyone knows it: do not report anything that complicates the anti-Family Federation story.

She gives a clear example of how this code is enforced. The MEXT protested against TV stations that showed content even vaguely favorable to the Family Federation. Some reporters faced effective bans. Even NHK, Japan’s public broadcaster, reportedly angered MEXT by airing material that could be seen as supporting the church’s claims. The ministry pressured NHK to change and limit its reporting.

Fukuda warns that the outcome creates a stifling atmosphere in which state pressure and media self-censorship feed on each other. Because the government’s interests line up with those of major left-leaning media outlets, even protests against this curtailment of free speech barely register. The chilling effect is complete.

In Chapter 9, Fukuda focuses on the donors whose voices went unheard. The government’s request for a dissolution order heavily relies on the claim of “large donation damages.” However, Fukuda argues that this claim is far less solid than the public has been led to think.

The Agency for Cultural Affairs and the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales claim to have interviewed many victims. Yet many of these cases were resolved years ago, and, importantly, no interviews were done with actual church members. Instead, the narrative was shaped by a selective group of former believers, many of whom left the church due to deprogramming, family pressure, or a loss of faith. Fukuda notes that the Lawyers’ Network often encouraged people to sue with the assurance: “You’ll get your money back if you sue.”

Active members who made large donations tell a very different story. They describe giving as guided by their faith and values, without coercion or threats. But in lawsuits involving the Lawyers’ Network, their testimonies are ignored, and incorrect statements appear as if pulled from a template.

Fukuda then looks at the 32 cases where the church was found liable for damages—cases that formed the basis of the dissolution request. A closer inspection reveals that most plaintiffs were former believers who had been kidnapped and confined, then pressured into renouncing their faith. These essential facts were not thoroughly investigated in the closed hearings leading to the dissolution order.

Fukuda warns that Japan could dissolve a religious organization based on a narrative built on half-truths and unverified assumptions.

In Chapter 10, Fukuda analyzes the “memorandum trials” and the resurgence of the mind-control myth. Before Abe’s assassination, the Family Federation had begun to win more civil cases. Courts were gradually leaning toward fact-based judgments. But after the assassination, this trend quickly reversed.

Fukuda believes the turning point was the “memorandum trial.” In this case, the Family Federation had decisively won in the lower courts. The facts seemed straightforward: an elderly mother made donations voluntarily, leaving behind memorandums and videos to prevent her family from seeking repayment. Her third daughter supported her choices.

Yet the eldest daughter, who wanted the donations refunded, separated her mother from the third daughter and proceeded with a lawsuit using guardianship rules and medical certificates. When the third daughter investigated, she found many false claims in her sister’s statements. The lower court ruled in favor of the church.

Then the Supreme Court intervened. It overturned the ruling, declaring that the mother had been “under the psychological influence of the religious organization.”

Fukuda criticizes this ruling as highly dangerous. It essentially reintroduces the discredited idea of brainwashing into Japanese law. If accepted, it could threaten religious freedom by allowing courts to invalidate any voluntary donation based on claims of “psychological influence.”

In Chapter 11, Fukuda revisits the 2009 Shinsei Incident—an alleged case of false accusation orchestrated by Public Security Police. The incident is often seen as a decisive moment that led the Family Federation to pledge compliance. However, Fukuda argues that this case was more a national policy operation by the Public Security Police than a legitimate investigation.

The representatives of a seal sales company allegedly linked to the Unification Church were arrested for violating the Specified Commercial Transactions Act. Yet, the legality of its actions was questionable. Police raided the company and the church, confiscated customer lists, and then contacted individuals, with alarming claims that “numerous complaints have been filed.”

However, the supposed victim whose complaint triggered the search was not even among the five named in court. This raises the likelihood that the case was set up backwards—charges were made first, evidence collected later.

A former member who testified for the prosecution had himself been abducted and confined before leaving the church, and there are doubts about the authenticity of his testimony. Fukuda concludes that Shinsei’s staff were likely victims of a false accusation and that the church was the real target.

She warns that opponents may have provided false information to the police and prosecutors, raising serious questions about the ties between anti-church activists and state authorities.

In Chapter 12, Fukuda examines another alleged false accusation: a stalking case that overlooked the reality of abduction and deprogramming. The chapter is about Mr. A, a member of the Unification Church who was arrested for violating the Stalking Prevention Law. He had been searching for Ms. B, his fiancée, after she suddenly vanished following a mass wedding. Given the long history of relatives abducting and confining church members, Mr. A feared she had been taken.

His concerns were not baseless. He later found out that Ms. B was in an apartment used by Takashi Miyamura, the deprogrammer central to Japan’s forced de-conversion network. Yet this key context was never discussed in court. Instead, the possibility of abduction—what motivated Mr. A’s search—was ignored. He was found guilty.

Fukuda speculates that the Public Security Police got involved because they suspected organized church actions. But no such actions were proved. If the police’s assumptions were wrong, then Mr. A was merely a pawn in a larger scheme to frame the church.

Like the Shinsei case, Fukuda argues, this is also a false accusation.