A homemade gun may have killed Abe but a manufactured moral panic pulled the trigger. It was a textbook case of anti-cult terrorism.

by Massimo Introvigne

The Japanese media are currently engaged in a curious exercise in rhetorical gymnastics: debating whether Tetsuya Yamagami, the assassin of Shinzo Abe, should be called a “terrorist.” Prosecutors, with the weary air of people forced to explain that two plus two equals four, insist the answer is obvious. Killing a political figure whom you did not know personally, for ideological reasons, is terrorism.

The defense, however, aided by a chorus of journalists and lawyers, part of Japan’s thriving anti-Unification-Church cabal, cry foul. Yamagami, they say, was no terrorist. He was a tragic son, a victim of maternal bankruptcy, a man whose mother’s donations to the Unification Church ruined his youth. Abe’s sin, apparently, was sending a congratulatory message to a Church-related event. In this telling, Yamagami is not a terrorist but a wounded avenger, a kind of folk hero with a homemade gun.

The debate is misplaced. Every terrorist has a personal story. I wrote several books about suicide terrorism based on alleged religious motivations. Every suicide bomber I studied in Palestine or Chechnya had grievances—real or imagined—against their targets. In “The Market of Martyrs,” a book I co-authored with well-known American sociologist Laurence Iannaccone, partly based on fieldwork in Palestine (Turin: Lindau, 2004), we even proposed an algorithm predicting which grievances were most likely to produce terrorists.

That terrorists have grievances does not make them non-terrorists. On the contrary, grievances are the raw material of terrorism. Most people with grievances do not become terrorists. Some do, and they should rightly be called terrorists and criminals. Yamagami’s case is no exception. His alleged difficult youth, even assuming all what he reports is true (which some doubt), is simply one more example of grievance turning to crime and terrorism.

But here, Japan’s debate misses something crucial: Yamagami is not just a terrorist. He is an anti-cult terrorist.

I wrote about this twenty-five years ago in the most authoritative journal devoted to the academic study of terrorism, “Terrorism and Political Violence.” The article was titled “Moral Panics and Anti-Cult Terrorism in Western Europe” (“Terrorism and Political Violence,” vol. 12, n. 1, Spring 2000, pp. 47–59). In that article I reviewed the literature on moral panics—those waves of collective hysteria where media, politicians, and activists inflate a perceived threat until society convulses in fear. Philip Jenkins and others had shown how moral panics against “cults” produced discrimination and violence. I argued that this violence had a name: terrorism. By 2000, there were already enough incidents to justify a new category: anti-cult terrorism. Arson attacks and murders of Jehovah’s Witnesses and LDS missionaries, bombings of Unification Church centers in France, assaults on Scientology—all fueled by moral panics branding these groups as dangerous “cults.” Predictably, my article was vehemently attacked by anti-cultists. Yet, the category stuck.

In 2018 the academic “Journal of Religion and Violence” asked me to serve as the guest editor of a special issue on “New Religious Movements and Violence.” I framed the subject by arguing that the relationships goes both ways. Some new religious movements are perpetrators of violence, from beating their own members to terrorist attacks. But other new religious movements are victims of violence and terrorism. I reviewed historical cases and noted recent terrorist attacks against Scientology churches in the U.S. Anti-cult terrorism was unfortunately alive and well, and by now an established category.

Fast forward to 2019. A teenager in Sydney, Australia, stormed a Scientology church, claiming he wanted to “rescue” his mother, a Scientologist. He killed a Taiwanese Scientologist. At trial, he was declared not criminally responsible—his family problems had made him schizophrenic. Anti-cultists celebrated the verdict as a victory. But the boy did murder an innocent man. The border between paranoia and ideologically motivated terrorism is thin. As the saying goes, real paranoids have real enemies.

Yamagami’s case is cut from a similar cloth. He killed Abe twenty years after his mother’s bankruptcy. His grievances against the Unification Church became combustible only because Japan’s media and activist lawyers had spent years stoking a moral panic against the Church. Grievances alone do not produce terrorists. Grievances plus moral panic do.

During the years of Communist terrorism in Italy, some Marxist sociologists were denounced—even by fellow Marxists—as “the evil teachers.” They never held a gun, never ordered an attack, but they created the moral panic against an alleged capitalist-political reactionary conspiracy that nurtured the Red Brigades. Japan has its own evil teachers. They are the journalists, lawyers, and activists who whipped up anti-cult hysteria, painting the Unification Church as a national menace. They now insist Yamagami is not a terrorist—because to admit he is would mean acknowledging their own responsibility. They would have to confess that they, too, played a role in creating the climate that generated the anti-cult terrorism.

The Japanese debate over whether Yamagami is a terrorist is not a debate at all. It is a cover-up. To deny Yamagami’s terrorism is to deny the existence of anti-cult moral panics. It is to absolve the evil teachers who nurtured the panic, and to pretend that grievances alone explain violence. But grievances are everywhere. What turns them into bullets and bombs is the moral panic. And in Japan, as in Italy, as in Sydney, the fingerprints of the panic-makers are all over the crime scene. Yamagami is a terrorist. An anti-cult terrorist. And those who refuse to call him one are not defending truth. They are defending themselves.

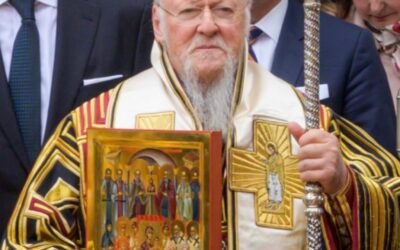

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.