East Asian anti-cultism stems from an unholy alliance between Christian heresy hunters and left-leaning lawyers, politicians, and media.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the CESNUR 2025 conference, Cape Town, South Africa, November 18, 2025.

Introduction

On November 4, IMboni Samuel Radebe of The Revelation Spiritual Home made a moving and powerful gesture of solidarity by visiting Seoul to see Mother Han, the leader of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (formerly known as the Unification Church), who was in jail on what many regard as trumped-up charges. Family Federation devotees keep permanent prayer vigils outside the prison. My wife, Rosita, and I also joined and encouraged them last month, as did religious leaders from various countries.

We also traveled repeatedly to Japan, where, following Shinzo Abe’s assassination, campaigns against the Family Federation and Jehovah’s Witnesses threaten their very existence. We also visited Taiwan, which has a better situation regarding religious liberty, but media campaigns and unjustified tax bills target specific minorities.

In 1967, American religious historian H. Neill McFarland devoted a book that soon became famous to what he called the “rush hour of the gods” in Japan. He argued that new religious movements (NRMs) were experiencing significantly greater success in Japan and other East Asian countries than in the West. After the 1995 sarin gas attacks of Aum Shinrikyo gave NRMs a bad reputation in Japan and beyond, some scholars argued that “the rush hour of the gods” had ended. And now there is a “difficult hour of the gods,” as East Asia is emerging as a relevant center of the international opposition to “cults.”

1 . Taiwan: From Martial Law to Taxes

China has a long tradition of opposing “xie jiao”—a term often mistranslated as “cults” but more accurately referring to “groups spreading heterodox teachings.” The imperial state saw xie jiao as threats to social harmony; the nationalist and then the Communist states saw them as threats to modernization, progress, and political control. Either way, the response was repression.

Taiwan inherited the Nationalist legacy of fighting “superstitious” religion. During the Martial Law era, the Kuomintang cracked down on groups deemed politically subversive or theologically deviant. Christian churches loyal to the regime were favored; those seen as xie jiao were repressed. Chiang Kai-shek had converted to Christianity and saw American-style Protestant Christianity as a modernizing and anti-Communist force. However, this applied only to mainline Christianity. Non-mainline Christian new religious movements were easily accused of being xie jiao.

One notable case is the New Testament Church and its Mount Zion community near Kaohsiung, which faced harassment and legal challenges for its apocalyptic theology and refusal to align with state-sanctioned religion. After a 1974 crackdown had disbanded the Mount Zion community, a second and equally violent raid, where devotees were severely beaten and some died, targeted members of the church around Taiwan in 1985. Only protests by American Pentecostals and the intervention of the U.S. government ended the persecution.

After Martial Law was lifted in 1987, Taiwan instituted religious liberty. But old habits die hard. In 1996, a crackdown on spiritual movements accused of being hostile to the ruling Kuomintang party targeted various groups. Ill-founded tax bills were issued against them, and one of the cases, concerning Tai Ji Men, remains unresolved after nearly thirty years. Mainline Christian churches and media outlets still exhibit antipathy toward “cults.” The recent campaign against the Christian Gospel Mission (Providence) is a case in point.

While Taiwan’s legal framework protects religious freedom, the cultural legacy of anti-cult sentiment—now also shaped by Christian heresy hunters—continues to influence public opinion and policy. Even in a democracy, the ghosts of authoritarianism still linger.

2. Japan: Deprogramming in a Nonreligious Nation

Japan presents a paradox. It is one of the most nonreligious societies in the world, as documented in the recent book by Ian Reader and Clark Chilson, “On Being Nonreligious in Contemporary Japan,” which emphasizes a widespread antipathy against organized religion and (in contrast with other scholars) also a decline in private religious belief. Yet, it hosts one of the most active anti-cult movements, with Christian pastors at the forefront.

Historically, opposition to “cults” in Japan came from two camps: secular leftists who saw them as irrational and suspiciously active in conservative politics, and Christian pastors who regarded them as heretical. Despite mutual suspicion, these groups formed a curious alliance. Pastors became deprogrammers, sometimes working alongside secular lawyers and activists.

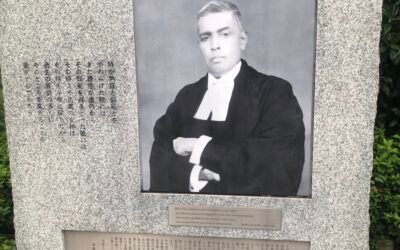

The practice of deprogramming Unification Church members in Japan began in the spring of 1966, spearheaded by Pastor Satoshi Moriyama of the Ogikubo Glory Church, affiliated with the Evangelical Church of Christ in Japan. He trained other pastors in techniques of deprogramming, which included abduction and confinement. Although not all opposing pastors were fundamentalists—some belonged to the more liberal United Church of Christ in Japan (UCC-J) or held left-wing ideologies—they shared a common goal: to compel Unification Church members to renounce their faith through psychological and physical pressure.

The deprogramming movement persisted for decades, with thousands of Unification Church members abducted and confined by their families under the supervision of Christian pastors. One of the most harrowing cases was that of Toru Goto, who was held for 12 years and 5 months before escaping. Pastors often justified these deprogramming efforts as “rescue” missions, despite their clear violation of human rights. Civil courts eventually ruled the practice illegal, and the Supreme Court rendered a civil decision in favor of Toru Goto in 2015. Still, no criminal charges were ever filed against the perpetrators.

Christian deprogrammers formed strategic alliances with secular anticult lawyers, particularly those affiliated with the anti-Unification Church organization known as the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales (NNLSS). This collaboration was formalized through a pact with the United Church of Christ in Japan, which provided theological cover for the lawyers’ legal campaigns against the Unification Church. Deprogrammed individuals were often pressured to file lawsuits against the Church, with lawyers and pastors working in tandem to build cases.

The 2022 Abe assassination, linked to grievances by the assassin against the Unification Church, provided the perfect storm. Public outrage, media sensationalism, and political opportunism converged to create a climate ripe for legal measures. The recent push to dissolve the Family Federation in Japan is the latest chapter in this saga. Pastors continue to partner with secular lawyers to lobby for governmental action.

This alliance is fragile. In a society skeptical of religion, Christian pastors must tread carefully. New post-Abe-assassination regulations on “religious abuse of children” in Japan target practices common among conservative evangelicals—such as taking children to long religious services, exposing them to teachings about divine punishment and hell at an earlier age, and preventing minor daughters from having abortions. Some of the very pastors who lead anti-cult campaigns may now find themselves under scrutiny.

3. Korea: Heresy Hunters and Political Purges

Korea’s anti-cult movement is perhaps the most aggressive in East Asia. And it’s overwhelmingly Christian. Protestant pastors have led deprogramming efforts, organized rallies, and lobbied for legislation targeting “cults.” Presbyterians mainly drove the original Korean Christian anti-cult movement. It emerged in response to a significant 20th-century loss of members—up to 20% in Korean Presbyterian churches—to religions they perceived as heretical, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Unification Church, the Olive Tree, Shincheonji, the Christian Gospel Mission, and the World Mission Society Church of God. Large non-Christian new religions, such as Daesoon Jinrihoe and Won Buddhism, also exist. While anti-cult groups sometimes target them as well, since Korea’s anti-cult movement mainly comprises Christians, their primary focus remains on Christian new religious movements “stealing sheep” from the mainline churches.

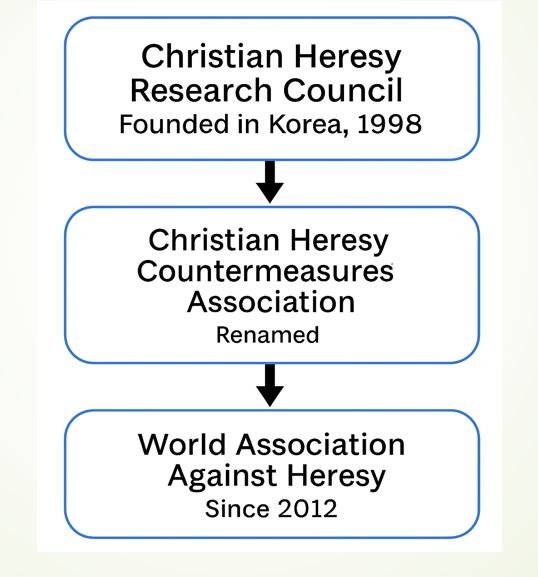

The origins of the World Association Against Heresy can be traced back to the Christian Heresy Research Council, founded in Korea in 1998 and later renamed the Christian Heresy Countermeasures Association. Since 2012, evangelical and fundamentalist pastors from other countries have been invited, and support has been received from Mainland China. The Korean organization was supplemented by the World Association Against Heresy. The Association openly supports deprogramming, which is not just a relic of the past in Korea. It continues today, often with the blessing of mainstream churches and the silent complicity of law enforcement. Shincheonji is the main but not the only target, and almost all deprogrammers are Christian pastors.

The recent arrest of Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon, leader of the Family Federation, is a case study in how anti-cult sentiment intersects with political repression. Her arrest on September 23, 2025, was immediately applauded by Japanese and Chinese counter-cultists, underscoring the transnational nature of the movement. On the other hand, the campaign against the Family Federation in Korea is part of a broader repression by the left-leaning government, which emerged from the 2025 elections, of religious groups that had supported the disgraced President Yoon and his conservative party, the People Power Party (PPP).

Even churches that oppose “cults” are not safe. Yoido Full Gospel Church, a vocal critic of heresies, found itself raided. Pastor Kim Jang-hwan, chairman of Far East Broadcasting Company and former president of the Baptist World Alliance, was also targeted. Busan’s Pastor Son Hyun-bo, a prominent Presbyterian preacher, was arrested in September and remains in jail.

This is the paradox at the heart of Korea’s anti-cult movement: the very churches that helped build the ideological scaffolding for anti-cult repression are now caught in the same net. Their theological purity did not shield them from a state apparatus that increasingly conflates religious conservatism with political subversion.

Conclusion: Unholy Alliances and Their Price

Opposition to “cults” in East Asia is unique for its disproportionate reliance on Christian heresy hunters. These pastors are simultaneously spiritual leaders, political actors, and media influencers, and sometimes deprogrammers and vigilantes. Their cooperation with secular and even anti-religious forces is pragmatic but perilous. While they share a common enemy, they do not share a common worldview. As recent events in Korea and Japan demonstrate, this alliance can backfire. Churches that help the state repress “cults” may find themselves repressed when the political winds shift.

Yet the alliance endures. For many conservative Christians in East Asia, the threat of “sheep stealing” by “cults” is more urgent than state encroachments on religious liberty. The result is a religious landscape where doctrinal boundaries are policed more aggressively than civil rights, and a political scene where theological deviance is punished with the pretext of fighting corruption.

Ultimately, the anti-cult crusade in East Asia is about power, politics, and the delicate balance between faith and fear. And while the dancers may change, the choreography remains the same.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.