A sociologist condemns the Unification Church-bashing. The anti-cult lawyer’s answer shows he ignores the basic principles of sociology.

by Massimo Introvigne

Attorney Masaki Kito has decided that sociology is too important to be left to sociologists. On November 20, he posted on X (formerly Twitter) to scold sociologist Noritoshi Furuichi, who had remarked on Fuji TV: “That society moved to bash the former Unification Church because of terrorism has left a very serious scar.”

This was not a throwaway line. Furuichi was alluding to a well‑known sociological concept: the moral panic. A moral panic occurs when media, activists, or politicians amplify a perceived threat, label a group as evil, and mobilize public hostility. Once a scapegoat is constructed, discrimination and violence can follow.

In fact, as a sociologist, I would argue that the “scar” and the moral panics were there before the assassination. When a minority is stigmatized as evil, feeble minds may feel justified in taking the law into their own hands.

But Kito, apparently unfamiliar with this basic theory, demanded: “I want an answer from Mr. Furuichi as a sociologist. Even in ordinary criminal cases, we are made to think about the background and causes. Why does thought stop when it is terrorism? The single word ‘scar’ is no answer.”

Kito went further, insisting that the “scar” must mean society’s failure to address “religious abuse of children” (a non-sociological concept invented by Japanese anti-cultists) until terrorism forced attention. He concluded: “It is of course a given that the shooting of former Prime Minister Abe is a crime. Everyone understands that. The problem is that we must continue to think about the prescription—the answer—for how to prevent such incidents from ever happening again. I want to hear that answer from Mr. Furuichi as a sociologist.”

It is good that Kito at least condemns the assassination outright. But others in the anti‑cult camp he supports are less clear. Journalist Eight Suzuki, while paying lip service to the fact that murder is “unacceptable,” notoriously offered this parable: “For example, if you suffer serious bullying, complain, but neither the teacher nor anyone responds, and then the principal praises the bully to the maximum and even gives him an award, it is natural that resentment would be directed at the principal. I think this case is close to that structure.”

In this parable, the”bullied pupil” is Yamagami and the “principal” is Abe. Would Kito condemn Suzuki for suggesting that resentment—and perhaps violence—against the principal was “logical”? Or does he reserve his indignation only for sociologists who refuse to parrot his narrative?

Kito’s claim that “religious abuse of children” caused the assassination is neither sociology nor sound legal reasoning—it is propaganda. Yamagami’s mother went bankrupt in 2002. Later, the local believers refunded half her donations. Yet, the assassination occurred twenty years later, in 2022.

Abe’s video message to a Unification‑Church‑related event hardly explains the timing. Politicians across the spectrum—Donald Trump, José Manuel Barroso, countless Japanese conservatives—had sent similar greetings for decades. If that were the trigger, Yamagami had twenty years and many “principals” to target. He did not.

What changed was not the bankruptcy of 2002 nor the political friendships that had started even earlier. What changed was the moral panic Yamagami was exposed to: the sustained campaign of hate speech and scapegoating against the Unification Church. That is when Yamagami was socialized into a subculture of hate. It is that subculture that may end up triggering violence. And since the panic continues, more violence may follow.

Kito accuses sociologists of failing to seek root causes. In truth, he demands they agree with him that the Church itself is to blame. But a normal application of sociological theory points elsewhere: the moral panic, not the Church, is the more likely culprit.

The irony is rich. A lawyer presumes to teach sociology, while sociologists quietly point to the obvious: scapegoating breeds violence. If Kito wishes to teach sociology, he should first learn it.

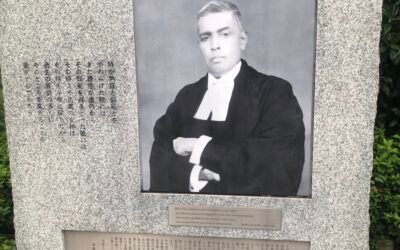

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.