Longread: an American student’s bitter reflections on his ten years in China, alongside the “ethnic cleansing” of Uyghurs and the persecution of Muslims.

by Mattias Daly

I first relocated to Beijing from the far-flung, mountainous province of Guizhou in 2009. There were countless differences between Beijing and the small city I had lived in, Tongren, and among them was the fact that Muslims were a highly visible presence in the capital. Rarely did I walk far in the streets without seeing men wearing kufis on their heads. Middle-aged and elderly Muslim men with thick beards stood out in this part of China where very few non-Muslim men wear facial hair, and Muslim women who could be identified by their headscarves could be seen in all neighborhoods. The places where a non- Muslim like myself (who, of course, doesn’t attend mosque) might see the most Muslims at any given time were the delicious halal restaurants all over the city, but in Beijing at that time you bumped into Hui and Uyghur Muslims almost anywhere, almost every day. They were a part of the greater community—a minority, yes, but a well-represented, widely-dispersed one.

Sometime in 2009 or 2010, an ethnically-Han Chinese friend in Beijing introduced me to the term “hamigua,” which means “cantaloupe.” The best cantaloupes to be eaten in China are those grown in Xinjiang province, which is also famous for its grapes, nuts, and sweets. For some reason, the word “cantaloupe” had become the racial epithet du jour for Mandarin speakers who wished to disparage Uyghurs. Several times I was warned, “those cantaloupes are all pick-pockets, be careful if you see them.”

I found the racist term disgusting, and I did not tolerate people using it with me, nor did I use it myself. It was an undeniable reality in those days that if a person came up to you on the street and surreptitiously offered to sell you a fancy cell phone furtively produced from a jacket pocket, far more often than not s/he had obviously Turkic features, and the common assumption seemed to be that these fellows were all Xinjiangese Uyghurs.

Reality is always infinitely more complex than racist epithets allow. China is populated by a number of Turkic peoples who are not Uyghurs, including Kazakhs, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Kyrgyz. Furthermore, not all Uyghurs are Muslims (even if they are born into Muslim families), and the guys who ended up in the criminal underground shouldn’t be paraded as representative of their religion or their ethnicity. Finally, a long history of ethnic violence and systemic racism in China deprives Uyghurs of crucial life opportunities. To the extent that the pickpockets actually were Uyghurs, many of them may have been pushed into crime by virtue of living in a country that robs them of options. In any event, those I heard blithely use the word hamigua did not seem to care about the differences between Muslim and non-Muslim Uyghurs, nor Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities. Rather, in daily conversation, a huge group of people were lumped into a single category based on unexamined assumptions. Racism functions in much the same way no matter where you find it.

Even though I heard the term hamigua used several times in 2009, and was even told by Han Chinese acquaintances in Beijing that some landlords refused to rent to Uyghurs, it was not until the summer of 2010 that I became aware of the seriousness of anti-Muslim and anti-Uyghur sentiment in China.

One day in July of that year, I noticed a foreign-looking young woman (I couldn’t really place where she might be from, but I did not think she was Chinese, or Uyghur) on the Muxidi Station subway platform, looking at the system map. In a moment of sudden outgoingness I walked up to the map, pretended to be reading it myself, and struck up a conversation in English. The young woman replied to my questions in perfect English and told me that she was Egyptian and visiting an aunt who lived in Beijing. We ended up riding the subway together and had a long, pleasant conversation. Before parting ways we exchanged phone numbers and agreed to meet for dinner.

We hung out a few nights later and discovered we were both on our way to studying medicine, me traditional Chinese medicine, and she western medicine. This mutual interest deepened our connection, and we began talking about the motivations behind our hopes of becoming doctors. Sooner or later she asked if I remembered where she was from. I replied “Egypt,” but she smiled shyly and said that had been a lie. “I’m from Xinjiang,” she told me, “I’m a Uyghur. But my aunt warned me when I came to visit her in Beijing that there is a lot of racism against us here. She said that since I speak good English, if people ask where I’m from I should lie and tell them I’m a foreigner. That’s better than running the risk of something bad happening to me if I meet somebody who discriminates against us.”

Her sudden revelation took me by surprise, but given some of the prejudiced things I’d heard before, I was not totally shocked. She asked me to help her keep up her charade if we bumped into anybody else, especially Han Chinese residents of Beijing, and I agreed. We hung out several more times, and as I got to know her better, the depth of her commitment to medicine became clear. The daughter of an internationally-educated western doctor who remained in his native Xinjiang to serve the Uyghur community, she fully intended to follow in her father’s footsteps. She told me that she was also inspired to pursue a life of service by her uncle, a once-handsome man who inexplicably caught an unknown disease that caused him to waste away over the course of several years. Finally the family found out, only because of a news report, that her uncle had been sneaking away to give blood far more often than was healthy, because he had a rare blood type. He kept this a secret for years, despite the toll it was taking on his health.

My friend’s intelligence, command of several languages, youthful energy, and beauty would have opened many doors for her if she desired a cosmopolitan lifestyle in one of China’s modern megacities or abroad. But there was nothing in such a life that she found seductive. She believed that the Uyghur community in Xinjiang was suffering due to a lack of highly-trained medical professionals (in addition to a host of other socioeconomic and political problems), and she fully intended to put her shoulder to the wheel in order to heal the sick in her own home city. As we met only a month and a half before I was to begin medical school in Shanghai, her selflessness and determination made a deep impression on me. We promised to stay in touch when she finally left Beijing a few days later.

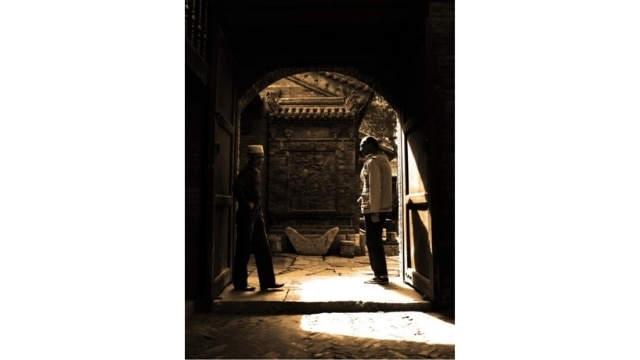

Readers are invited to look at the image above. I doubt I will ever photograph a warmer smile than that beaming from the man in the center wearing a kufi (taqiyah) atop his head. Whenever I read asinine, racist attempts to justify the PRC’s oppression of Muslims, such as those author of “The Three Body Problem,” Liu Cixin, made when interviewed by Jiayang Fan for The New Yorker (“Would you rather that they be hacking away at bodies at train stations and schools in terrorist attacks? If anything, the government is helping their economy and trying to lift them out of poverty”), I cannot help but recall this man’s gentle, infectiously joyous and loving face. A poisonous mix of extreme callousness and willful ignorance is necessary for anybody to think that a small number of terrorist attacks committed by a handful of extremists justify the wanton brutalization of millions of people through concentration camps, slavery, billeting, obliteration of culture and language, and outlawing religious belief.

After arriving in Shanghai in the fall of 2010, the rigors of my first year in medical school (a mix of traditional Chinese and western medicine, taught entirely in Chinese) swiftly deprived me of the spare time I would have needed to explore the city like I had Beijing, much less ponder distant-seeming social issues. However, I did notice that, just as in Beijing, Muslims—often with the Turkic features common to Uyghurs—could be seen all over the Shanghai metropolitan area. Just as in Beijing, Muslims appeared to be a minority who were firmly a part of the city, whatever problems might have been lurking under the surface.

In early 2013, Xi Jinping took power. In the first year of his reign a sort of enthusiasm was palpable in the air. The reason was simple—he had promised to tackle the Chinese Communist Party’s tremendous corruption, which was the bane of common people’s lives. During his first year at the helm of China’s government it was not yet clear that the purges of corrupt officials—news of which was followed excitedly by the public—were really purges of his political rivals. Furthermore, the internet remained as open as it had become under the previous premier, Hu Jintao, with people enjoying the unprecedented new ability to publicly express themselves. The censorship of blogs and microblogs was still relatively light (by CCP standards), and the brand-new app WeChat on the newly-invented, wildly popular smart phones was connecting people in exciting ways. There was, to those prone to getting caught up in historical moments, something of a “spring is in the air” feeling at that time. The general enthusiasm that buoyed people through the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, the recovery from the fiscal crisis shortly thereafter (a recovery that involved building amazing high speed rail trains), and the Shanghai World Fair in 2010 was coupled with the opening of the internet to free-ish speech, increasing internationalism, a new consumer culture (Taobao! Shopping malls!), and, of course, the economic advancement that touched most people’s lives quite directly. These things had greatly improved national morale, and now there was a new boss in town who promised to boldly sweep out the corruption from within the Chinese Communist Party itself. Life was looking up! Long live Chairman Xi!

I can’t remember precisely when the proverbial skies began to darken, but as soon as this process began, it unfolded quickly. What I do remember is the moment when I could tell that the good old days of Hu Jintao’s “let’s open up to the world for the Olympics” China were definitively over. A wealthy employer and then patron of mine had invited me to visit him in Shandong province, where he put me up in a hotel. On my first night, he accompanied me as I took my luggage up to my room and then sat for tea, which we poured while sitting on easy chairs a good six meters away from the door. My room was the last on a long hallway, devoid of people, our voices were muted by the heavy carpeting, and we were speaking fairly quietly, so there had been no reason to close the door as we caught up over hot tea. However, at some point my acquaintance began reciting the basic boilerplate about what an amazing man Xi Jinping supposedly was. I remember, distinctly, how he even went so far as to wax poetically about how Xi has “facial physiognomy that shows he is destined to be an emperor.” This statement, which sounds bizarre to foreign ears, is a fairly common thing to hear in China, where auguring people’s futures on the basis of their facial features or palmistry is still de rigueur. But this was the first time I was to hear it coming from a person whose opinion I took fairly seriously.

I politely heard my friend out, before I interjected to say that in addition to such rosy plaudits, I had also heard an increase in misgivings about Xi in recent months, especially with regard to the way in which his purges of “corrupt officials” looked more and more to be purges of political adversaries. My friend suddenly became very solemn and made a gesture with his hand for me to stop talking. He looked all around, then stood up, walked to the doorway, peered into the still-empty hallway, softly closed and locked the door, and then wordlessly returned to his seat. Leaning forward until we were inches from one another, he said, in a hushed voice, “Yes, well, it is true, there are in fact many people who say Xi Jinping seems to be turning into something of a tyrant.” He withdrew into silence, and the discussion ended there.

My acquaintance’s exaggerated caution might have been funny had he not been deadly serious. I had never seen this man, a rich CEO of a large company with thousands of employees and hundreds of storefronts, offices, and factories around China, ever display anything other than a penchant for jolly bombast and, when he was drunk, rumbustious overconfidence. To see him become so fearful—even when nobody could possibly have been near our room… It was a shock, and it reminded me how much danger lurks in PRC citizens’ lives, even if they enjoy a real degree of wealth, power, and prestige. How much more danger must there be, when those three things are missing.

As the months and years wore on, anybody who was paying attention could see that Xi Jinping was avidly clamping down on freedom of speech and anonymity on the internet, freedom of reportage in the news media, freedom of expression in entertainment, freedom of opinion and research in the educational arena, freedom of religion, and so on and so forth. Even “effeminate” traits in male celebrities ended up forbidden, lest they subvert Xi’s fantasies of a macho-man national identity. The creep gradually picked up speed, until, within a few years, the enthusiasm of early 2013 was replaced by the feeling that a new, quieter, digitized-and-networked sequel to the Cultural Revolution was coming into being.

I suppose it was about 2016, as the mass surveillance “panopticon” and the early announcements of the coming Social Credit Score became widespread knowledge, when the unabashed praise for Xi Jinping disappeared from many of my Chinese friends’ and acquaintances’ lips (while others went in the exact opposite direction, some of them now breathlessly referring to Xi as “Dada,” a term from certain local dialects that can mean “daddy” or “uncle”), and when ever increasing numbers of friends—foreign and local—returned to quietly-but-openly expressing their disgust for the CCP. The “world’s biggest mafia” and the “world’s biggest cult” are both terms I learned by hearing them repeated by PRC citizens describing the Chinese Communist Party. Some of the things I heard from people who suffered personally due to the CCP’s misrule were no less lurid and terrifying than what is documented in The Spider Eaters, The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk, The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and many other books. But it is one thing to read of such things in English, a hemisphere away from the land their authors emerged from. And it is something very different to sit and listen in tense silence, with a person who refuses to let you break eye contact, as he or she recites a list of these terrors from lived, personal memory.

I had first visited the “people’s republic” of China in 2007, and moved there in early 2008. I lived in China until the end of July 2017, and continued to visit regularly until the end of 2019, sometimes for several weeks at a time. The variety of traditional Muslim headwear seen in the photo above was an everyday sight all over Beijing and Shanghai until the mid-2010s. By the time I left China in 2017, kufis and hijabs were gone from the streets of the neighborhoods I frequented in Beijing. I only ever saw them on the waitstaff on the greatly-reduced number of “Northwest Cuisine” (西北菜) restaurants that served dishes common to Xinjiang, Gansu, and Qinghai provinces, which have large Muslim populations.

When I moved back to Beijing from Shanghai in the fall of 2013, the Muslim population was still highly visible, but on October 28 of that year the tide began to change. It was on that day that a car crashed into a crowd on Tiananmen Square, killing two civilians. The driver was said to be a Uyghur Muslim man. The act of violence, which shocked the nation, was labeled a terrorist attack.

Half a year later, in March of 2014, there was another attack attributed to Uyghur Muslims, this time in Yunnan province, when knife-wielding individuals killed thirty-one people in a train station. It was, to be sure, a horrific incident, and the country was paying rapt attention. We all knew that the PRC’s national security apparatus had been fully mobilized to come down on Xinjiang “separatists,” but we could not have known that Xi Jinping ordered counterterrorism forces to “be as harsh as them, and show absolutely no mercy” in secret speeches whose text was revealed in 2019 by the New York Times.

Still busy with medical school, I did not follow the news coming out of Xinjiang closely. But in late 2015 the province was once again on the tip of people’s tongues, when Uyghurs alleged to be terrorists were found in or chased into caves in Xinjiang province, and were then killed en masse with flame throwers. Many Han Chinese people I knew openly praised the brutality with which the alleged terrorists were crushed, reacting no differently than I am sure many people in countries all over the world do when terrorists (alleged or actual) are eliminated.

At this time I started to notice an increase in the general willingness to speak of Muslims, especially Uyghurs, in incredibly disparaging terms—terms that growing up in America taught me to instantly identify as racist, but which teachers and elders of mine in China insisted were simply good common sense. Many times, for instance, a middle-aged martial arts instructor of mine with a love for holding court with his students after class would go into spontaneous anti-Uyghur digressions. Whenever it was suggested to him that he was being too prejudiced, he would quickly defend himself with the following reasoning: “No, no, no, I’m not anti-Muslim, you see. We’ve had Hui Muslims in China for centuries, they’re just fine, they’re grateful to be here and they don’t cause trouble, it’s the Uyghur Muslims who are ungrateful and dangerous and backward, they’re different. If they would just assimilate with Han culture like the Hui, there wouldn’t be any more problems.” It goes without saying that this defense was specious, but it is also worth mentioning that being viewed as “model minorities” has not spared Hui Muslims from recent rounds of religious persecution under the CCP.

The Chinese government, as commentators often gush, does things quickly. And it was with quickness that the population of Uyghurs began to plummet in Beijing. I do not know exactly how they were “dealt with,” but by 2015 or 2016, it became a rarity to see kufis and headscarves anywhere outside of a now greatly-reduced number of halal restaurants or in neighborhoods like Niujie in Beijing’s Xicheng District, which holds a large mosque with a thousand-year history.

I do not know if Hui Muslims, whose features are generally very similar to those of Han Chinese, were removed from the city, or if they remained in Beijing while ceasing to don traditional Muslim headwear in public or grow beards. The Uyghur population, however, noticeably plummeted, so that by 2016, if I saw a Uyghur-looking person on the street, my unconscious reaction would be, “whoa, how’d you get here?” In my medical school class I had classmates from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, both of whom were used to being asked if they were Uyghurs on account of their Turkic features. But they began expressing nervousness about the increasing anti-Uyghur sentiments in Beijing and told me they were now quick to tell people they were foreigners.

Ethnic cleansing was taking place all around us, plainly visible, and yet I never heard it named. Amid China’s relentless churn of change; the utter silence in place of the public dialogue and dissent that exists where there is freedom of speech, press, and protest; the mass-eviction of millions of poor migrant laborers from Beijing that was occurring simultaneously; and our own crushing med school course loads… Amid all this, somehow, we did not really notice. We have all heard the myth that a frog won’t perceive the temperature rising if it is in water coming slowly to a boil. This is not true —frogs have the good sense to leap free of the pot as soon as they sense the peril. The myth persists, not because it says anything about frogs, but because it describes us humans so perfectly.

Shortly after I moved back to Beijing from Shanghai, in the early autumn of 2013 (before the aforementioned terrorist attacks on Tiananmen Square and in Yunnan), my Uyghur medical student friend from the subway platform passed through Beijing. Having not seen one another in three years, but having stayed in touch over the phone, we were happy to finally catch up in person. She told me she had completed a portion of her medical studies in China and was planning to continue her studies overseas, in a country where the quality of medical education is miles above what it is in China. But she remained as adamant as ever that there was no way she would remain abroad. She intended to come home soon to be close to her family and to provide service in Xinjiang. After that lunch we stayed in touch for a while, but the rigors of my studies and the vicissitudes of life caused me to go quite some time without exchanging any messages.

I cannot remember when the first rumors of the concentration camps in Xinjiang started to filter into my life in Beijing—it may have been 2016, or 2017. However, in the summer of 2017, the American journalist Ben Dooley, a friend of mine who was working for Agence France-Presse in Beijing, went to Xinjiang to research the oppression of Uyghurs there. What he described to me when he returned sounded extremely similar to what can be seen in Vice’s 2019 documentary, “China’s Vanishing Muslims: Undercover In The Most Dystopian Place In The World.”

Ben described being followed and questioned everywhere he went, while forbidden from visiting most of the places he hoped to go. Needless to say, he did not visit any internment camps. But he described a highly disturbing world to me, one in which checkpoints, x-ray scanners, and surveillance reign. A world where Uyghurs cannot even go grocery shopping without passing through metal detectors and showing ID, and where no locals dared to speak to him. His conclusion—and this is not a man prone to hysteria—was that the rumored archipelago of concentration camps almost certainly existed. At this time the Chinese government was still flatly denying the existence of the camps; only in October of 2018 did they perform a Kafkaesque volte-face, admitting that the hundreds of concentration camps are there, but calling them “voluntary vocational education centers.”

Ben Dooley’s observations in Xinjiang sent a shock through me that has never worn off. Ben’s story filled me with gut-twisting worry about the fate of my medical student friend from Xinjiang. It also stunned me into realizing that I witnessed the slow disappearance of Uyghur faces in particular and Muslim garb in general from the streets of Beijing, a city I lived in for five and a half years, without ever comprehending the gravity of the situation. Quietly, but with industrial efficiency, Beijing had been ethnically cleansed. The people had gone in a trickle or a rush—I never saw how, and the news and propaganda organs were silent on this front – and were forced to return to their “hometowns” (the localities where their hukou, or official “household registration” documents declared they belonged). They returned to a province remade as an open-air prison under Chen Quanguo, a CCP official who cut his teeth running the police state that is modern-day Tibet. The vast majority of us in Beijing—local and foreign alike—were oblivious to the forced relocation of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs that took place around us.

Disgusted with myself for falling out of touch with my friend for so long while all this was happening, I immediately tried to give her a call. Her number was out of service. I have called the number countless times since then, but nothing has changed.

Of course, I cannot conclude from a single disconnected phone number that my friend was or is imprisoned in a concentration camp in Xinjiang. It is possible she continued her medical studies in the west, and found a way to remain overseas. It is possible she returned to Xinjiang, where she suffered a “lesser” form of imprisonment than concentration camp, such as “merely” having to stay in the city where her hukou is registered, perhaps in one of the family homes where one million CCP cadres are regularly sent to live, sleep, eat, snitch, and… worse.

What I do know is that people like my friend are labeled as high-risk under the CCP’s paranoid metrics, which seek to weed out Uyghurs who have studied or worked abroad. As she is a multilingual woman with overseas experience who also possesses a powerful sense of Uyghur identity, the algorithms that decide whether or not a person is “dangerous” would have flagged my friend long ago.

Shortly after I failed to reach her on the phone in 2017, while I was still in Beijing, I realized there was no way I could look for her, even on the internet, without putting myself in very real danger of persecution or imprisonment. Even now that I have left China with no intention of returning until the Communist Party’s reign finally ends, to look for my friend from afar would make life worse for her and even her family. The PRC government is notorious for punishing Uyghurs in Xinjiang for actions done on their behalf overseas.

You may have noticed that I have not named my friend, her hometown in Xinjiang, or even the country she traveled to study in. The situation is so dire in Xi Jinping’s China that I don’t even toy with the fantasy of trying to help my friend directly. If she is in a concentration camp, and it comes to the attention of the CCP that there is an American using the internet to try and turn her disappearance into an “international incident,” whatever privations she is suffering will only worsen. Torture and rape are widespread in the concentration camps (in addition to the prisons and camps used to hold Tibetans, Falun Gong practitioners, human rights lawyers, activists, and too many others).

If my friend is not imprisoned, but remains in China, placing her in the spotlight could still worsen her condition. In Xinjiang, family members of Uyghur Radio Free Asia reporters who work outside of China have been arrested as a way to exact revenge upon their journalist relatives. Even Uyghurs living outside of China have been intimidated, harassed, and put under surveillance, in addition to facing forced repatriation. The PRC government is so brazen in its campaigns to stifle dissent that is has parked fake Chinese police cars outside Uyghurs’ homes in Australia. With these things constantly in mind, it is hard to imagine what, if anything, I could do to help my friend directly. For what little it is worth, my best and only option seems to be to publish this essay.

The disappearance of Muslims from Beijing between 2013 and 2016 was a preview of a second wave of disappearances, one that was much more visible, perhaps simply because its goal of removing two million people from the city within two years made subtlety and secrecy impossible. This wave of disappearances focused on migrant workers. Classified as “migrants” because they are deprived of “Beijing residence permits,” these were the people who, beginning in the 1980s, arrived in search of work. They built the sea of gleaming skyscrapers and took the hard, low-paying jobs that allow a city to function, often putting down roots of their own. Despite not having residence paperwork, migrants owned tens of thousands of small businesses around Beijing, including most of the restaurants where I ate. Many so-called migrants raised their families in the city. Even people born in the city were not free of this label— there is no “birthright citizenship” in Beijing. And so, almost overnight, two million of these people were ordered to leave.

Through a process that began in 2016 and reached fever pitch in 2017, migrants’ lives were turned upside-down. I personally witnessed the sudden emptying of entire streets filled with hundreds (yes, hundreds!) of shops. Without warning, motley squadrons of “local bylaw enforcement officers” would descend on a street to gut shops or knock down dwellings, littering the streets with a building’s contents while milling crowds of helpless occupants and armed police looked on. As soon as they were stripped of their interiors, storefronts would be bricked up. I saw this process unfold in two neighborhoods. It took only three days to complete. The violence these actions wrought against the fabric of communities was impossible to ignore, and the city seethed quietly with anger, with even some “official residents” of Beijing openly voicing opposition to the evictions and offering charity to the displaced.

During this campaign against the working poor, undertaken beneath the banner of “socialism,” I lost touch with yet more friends and acquaintances. One was an incredibly kind medical massage therapist, Dr. Zhang, who had a small clinic I used to frequent in 2010. Seeing my interest in traditional massage, Dr. Zhang eventually became a mentor to me, and would invite me to enormous lunches she cooked for her staff. When I returned to Beijing in 2013, I lived halfway across the city, and I rarely dropped in on Dr. Zhang’s clinic. But when I went to her neighborhood in the summer of 2017 to share the news that I’d finally finished medical school, my jaw dropped. Every last storefront, one block after another, was bricked up and painted over. Hundreds of small businesses were gone, leaving no evidence of the area’s recently-bustling street life, and no traces of its former inhabitants. Another goodbye.

That summer also saw the death of the dissident writer and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Liu Xiaobo. A prisoner of conscience for many years, he was “freed” while in the final stages of liver cancer. He asked to travel to Germany for treatment upon his release, but the request was refused, and he died in a Chinese hospital one month later.

Having completed a yearlong internship in the China-Japan Friendship Hospital in Beijing, I knew how the local hospitals functioned and how much power Communist cadres wield in them. I understood that Liu, who remained incarcerated until his cancer was nearly inoperable, was never meant to be saved. He was sent to a hospital on the verge of death so that the international news could not report that he died in prison. Having graduated from medical school only days earlier, and preparing for further medical training with a “Chinese Government Scholarship,” the way in which Liu’s fate was sealed made my blood run cold. I was on a track leading to possible employment in a state-run hospital, my tuition and living expenses paid for by a government that was furiously building concentration camps, and which had no compunction about withholding medical care to a peaceful dissident of international standing until death was at his door. To what degree would I have to sacrifice my values to remain on this path? What would I have done were I an intern in the hospital Liu was released to?

It was a summer of one-sided farewells, uttered to disconnected telephone numbers, bricked-up storefronts, and to those who I imagine would have attended a vigil for Liu Xiaobo, could such a vigil occur in Beijing without it leading to mass arrests. In spite of the fact that I would be leaving a career, a life built over the course of nine and a half years, and countless friends, I realized that my time in China had come to an end. I left, not because I no longer felt at home there, but precisely because I was beginning to see myself as a part of this society instead of just a “foreign guest.” Fully fluent in Mandarin, fully versed in local customs, and fully aware of the direction Xi is steering the country in, I could no longer sit and watch silently, telling myself that my silence is justified because, as a foreigner, I am in no place to judge this nation. A decade is long enough to become a local. But there is only one place in the PRC where the type of local I am willing to be is permitted to exist, and I confess that I am not brave enough to choose a life of concrete cells and barbed wire, as Liu and countless other prisoners of conscience have.

A decade spent in China left me with questions that will take a lifetime to work through, but it also answered one that haunted me as I grew up in a part of the United States where the history of Hitler’s holocaust was a constant presence in the school curriculum. I always used to wonder what feelings swirled in the hearts of the countless civilians who stood by as the Nazis consigned millions to concentration camps. A range of possible answers filled my mind, but there was one I never once considered: nothing, nothing at all. Not only the Uyghurs but most outward signs of Muslim faith were eradicated from the very city I lived in, and I barely batted an eye. I did not even think to call my own Uyghur friend until an eyewitness described to me the open-air prison that Xinjiang had become in 2017. It now occurs to me that a great many rank and file German citizens of the 1930s and 40s may simply have been… not paying any attention.

I was not alone in my ignorance, nor was this ignorance limited to “the Uyghur question.” Over dinner in Beijing the night after Liu Xiaobo’s death, I asked two Chinese friends who were openly critical of the CCP if they had heard the news of his passing. Both in their thirties, they did not even know who

Liu was, and one produced his phone to look him up on Baidu. He was directed to an anodyne, “politically correct” paragraph meant for those who live behind the Great Firewall. The page did not even mention that Liu was dead. My friends looked at me blankly, and when I tried to explain Liu’s global significance, their eyes quickly glazed over. The massacre on Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989 has been so buried in China that it is not hard to find young people who say they have never even heard of it, while some others insist that it is a rumor, or “fake news.” But can we blame ignorance of the plight of the Uyghurs or China’s human rights activists on CCP censorship alone? How much attention are those of us living outside of China paying to the slow-motion cultural genocides affecting Uyghurs, Tibetans, Mongolians, and other minorities in China? Would attention, alone, even amount to anything?

Two nights ago I visited a Uniqlo in downtown Taipei with a friend. While she shopped, I asked a clerk what steps the company has taken to ensure it does not source cotton produced through forced labor in Xinjiang. Unable to answer, the clerk went and found a manager, who came over and chirpily told me, “we frontline staff don’t get to know things like that, maybe you could call company headquarters on a weekday,” and then walked away. For a moment I was satisfied with his answer, before I noticed with alarm the ease with which my concerns were drifting off into the fluffy realm of disconnection and complacency. I turned to the clerk and asked her to take down my phone number and email address, and to ask somebody in Uniqlo management who could answer my questions to contact me.

It was a miniscule gesture, and if I am the only person who ever does this, certainly an ineffectual one. But it was infinitely more than blithely letting those who have been yanked from sight, fall from mind. It was the least I could do for my unnamed, long-lost friend. And, tiny though it was, this action was one I could not take in Beijing without risking the loss of my freedom. The CCP has taken away people’s right to ask questions, because questions have power. This won’t be the last time I exercise my right to call for an answer, and I hope I’m not alone.

Mattias Swenson Daly is a Kiwi-American researcher, translator, and writer based in Taiwan. His writings and translations span religious, historical, political, and arts topics. One of his translations, Taoist Inner Alchemy: Master Huang Yuanji’s Guide to the Way of Meditation, was published in 2024 through Shambhala Publications. In 2023 he published Ungrounded Certainty: The Methods, Texts, and False History of Sexual Inner Alchemy in the Scholarly Imagination (無中生有:學界想象中的陰陽丹法文本與虛構的歷史), an original monograph written in Chinese, through Shin Wen Feng Printing Company. Prior to living in Taiwan, he spent a decade in China.