A specialist in fact-checking demonstrates that the real story of Shinzo Abe’s assassin was very different from the media’s anti-Unification-Church tale.

by Massimo Introvigne

A very important article has just been published in Japan, and it deserves more than a passing glance. It is not another reheated editorial about the assassination of Shinzo Abe, nor a perfunctory courtroom dispatch. It is the work of Hitofumi Yanai, one of the most respected fact‑checkers in Japan, who has taken the trouble to sit through twelve of the fourteen hearings of Tetsuya Yamagami’s trial and to compare what he saw with what the media reported. All his comments are supported by precise references to statements by Yamagami and his relatives during the trial. The result is devastating: a catalogue of inaccuracies, omissions, and distortions that reveals how the press has constructed a morality play from fragments, while ignoring inconvenient facts that do not fit the script.

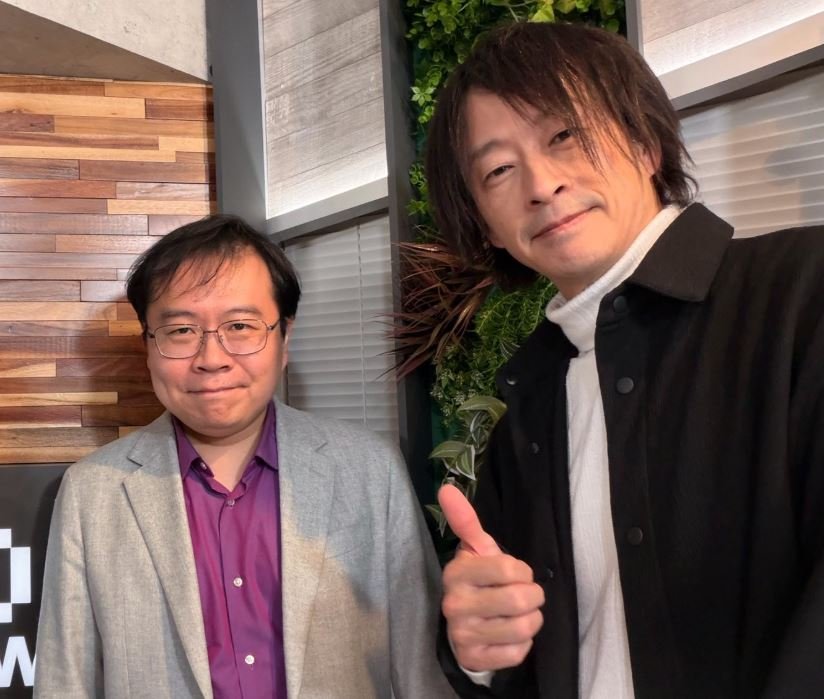

Yanai is not a marginal blogger. He graduated from Keio University, reported for the “Sankei Shimbun,” became a lawyer in 2008, and since 2012 has run GoHoo, Japan’s pioneering misinformation verification site. In 2017, he founded the Fact‑Check Initiative and, in 2018, published “What is Fact‑Checking?,” a book that won the Ozaki Yukio Memorial Foundation’s Book of the Year Award. His credentials are impeccable, his independence proven. When he says the media have misled the public, he speaks with authority.

What did he find? First, the myth of a childhood destroyed by religion is false. Yamagami’s early years were “very smooth” until 1994, when he was in his second year of junior high school. There was no maternal abuse, no starvation, no forced prayers. The volatile figure was the grandfather, who sometimes brandished knives and told the children to leave. Financially, the family was secure, supported by pensions and company income. The siblings all attended good schools. Yamagami himself attended Nara Prefectural Koriyama High School, one of the “Big Three” prefectural high schools in Nara. He passed the entrance exam to a private university but chose not to go, not because of poverty or maternal obstruction, but because he lacked the will and disliked the college. He tried firefighting, failed, joined the Maritime Self‑Defense Force, and later enrolled in law school, only to lose interest and be expelled after about a year—for reasons unrelated to financial problems. The narrative of a brilliant youth crushed by a fanatical mother collapses under scrutiny.

Second, the mother’s long travels to Korea, another staple of media melodrama, began only in 2005, after all the children had grown up. During their minority, she never left for more than two nights. Children were under the grandfather’s care, and meals were prepared in advance. Yamagami himself never claimed hardship from her travels.

The financial relationship with the Unification Church, too, is more complex than the headlines suggest. Yes, the mother donated something more than ¥100 million. Still, from 2005 onward, the family received monthly repayments from the local community of Unification Church believers, and by 2014, a total of ¥50 million had been reimbursed under a signed agreement. Yamagami himself considered the matter “resolved” and had no intention of suing. The image of a son driven to murder by unresolved financial ruin is simply false.

Third, the real source of family violence was the elder brother. After failing the university entrance exam, he assaulted his mother so severely that she suffered fractures and also terrorized his younger sister. He later struggled with psychiatric illness before committing suicide. Yamagami distanced himself from him, and after the brother’s suicide, he withdrew from the family altogether, not seeing his sister for more than five years before the crime. Again, the facts point to disengagement, not persecution.

The most explosive revelations concern motive. Yamagami was not an anti‑Abe fanatic. On the contrary, he admired Abe’s Korea policy, denied anger against him, and even voted for Senator Kei Sato, the politician for whose re-election Abe was campaigning when he was assassinated.

His information about Abe’s ties to the Unification Church came almost entirely from the anti-cult journalist Eight Suzuki’s website. His original plan was to attack Korean Church leaders, but when he discovered no such leaders were visiting Japan, he turned to Abe only five days before the crime. At the time of the attack, he was drowning in debt of more than ¥2 million from building homemade guns, unemployed, and desperate. He admitted he felt “cornered” and needed to cause an incident. The shooting of Abe was thus a late, improvised decision, not the culmination of years of rage.

Even then, Yamagami’s intention was not simply personal vengeance but media impact. He fired at a Unification Church building beforehand to ensure his motive would be understood. He welcomed the subsequent dissolution request against the Church, calling it “the proper outcome.” He admitted that he thought and hoped that the media coverage of the assassination would turn against the Unification Church.

He acknowledged that the reporting of his case had been inaccurate. He even suggested he would return the large sums of support money he had received, since the trial would reveal him to be a different man than the model painted by the press.

Yanai’s article is a frontal assault on the mainstream narrative. It shows that the media, in their rush to stigmatize the Unification Church, have omitted crucial facts: the absence of maternal abuse, the financial settlement with the Church, the admiration for Abe, the late decision to target him, and the role of debt and desperation. What emerges is not the story of a victim of religion turned assassin, but of a man adrift, estranged from family, crushed by debt, and seeking to damage the Church through terrorism. The real scandal, Yanai suggests, is not only the crime itself but the way the media have distorted it.

The assassin wanted to damage the Unification Church by ensuring his motive was understood. The media, by distorting his life story, have helped Yamagami achieve his aim but have damaged something else: the public’s ability to know the truth. They have turned a desperate man into a symbol, a family tragedy into a political allegory, and a complex case into a simplistic morality tale. Yanai’s fact‑checking restores the missing complexity and, in doing so, reminds us that journalism without accuracy is not journalism at all, but propaganda. The trial may be ending, but the fact‑checking has only begun. And perhaps the most uncomfortable truth is that the press, not the assassin, has been the most reckless actor in this drama.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.