What is a “cult”? The term is used in such a loose way that most Australian churches and religious organizations can be targeted.

by Bernard Doherty.

Article 2 of 2. Read article 1.

In the first article of this series on Victoria’s Inquiry into the Recruitment Methods and Impacts of Cults and Organized Fringe Groups, I examined previous Australian inquiries on “cults.” What is different about this inquiry from earlier inquiries?

A historical survey of such earlier waves of what might be called “cult controversies” in Australia suggests that when these periods of heightened concern about so-called “cults” occur, one can usually identify one core social issue or concern around which an idea of what I would call “cult menace” can be socially constructed.

For example, the Anderson inquiry can be partially attributed to broader Cold War concerns and the development of a mythology of “brainwashing,” as well as controversies about the attempt by a rogue member of Scientology to infiltrate the Victorian branch of the Australian Labor Party during the early 1960s.

During the Second World War, Jehovah’s Witnesses found themselves targeted because their apocalyptic and pacifist stance was seen as threatening to the morale of the broader war effort.

In this current instance, the context of this inquiry can, I suggest, be squarely contextualised around broader societal discussion of two core issues of legitimate concern within the wider Australian community: a concern over domestic and family violence which has been building in recent years in the wake of a series of high-profile homicides of women and media saturation, and, particularly in Victoria, concern about the rise in political extremism in post-COVID Australia—though the former has been more foregrounded within the inquiry hearings thus far.

Despite the ongoing scourge of domestic violence in Australia, wider public discussions around coercive control have increasingly found themselves being directed to religious groups, rather than to individual perpetrators and their original and appropriate application in the study and prevention of intimate partner violence. This is a case of the expansion of the domain of an idea beyond its immediate initial theoretical context—much like the idea of so-called “brainwashing” originally emerged in Cold War studies of communist attempts, largely unsuccessful outside stringent conditions, to psychologically modify human behaviour.

In this regard, three important observations are worth noting.

First, the most obvious, trying to inaccurately expand coercive control ideas beyond their theoretical grounding in the study and prevention of intimate partner violence risks confusing the issues and muddying the legal waters. The legal provisions introducing ideas of coercive control are recent innovations in Victoria and other Australian states, and any expansion of coercive control laws away from their intended purpose of preventing domestic violence and prosecuting perpetrators risks making them legally ineffective. Expansion of laws beyond their intended purpose is always problematic. In this case, it may be potentially dangerous, both for religious groups, but especially for women and other victims of domestic and family violence, whom these laws are designed to protect.

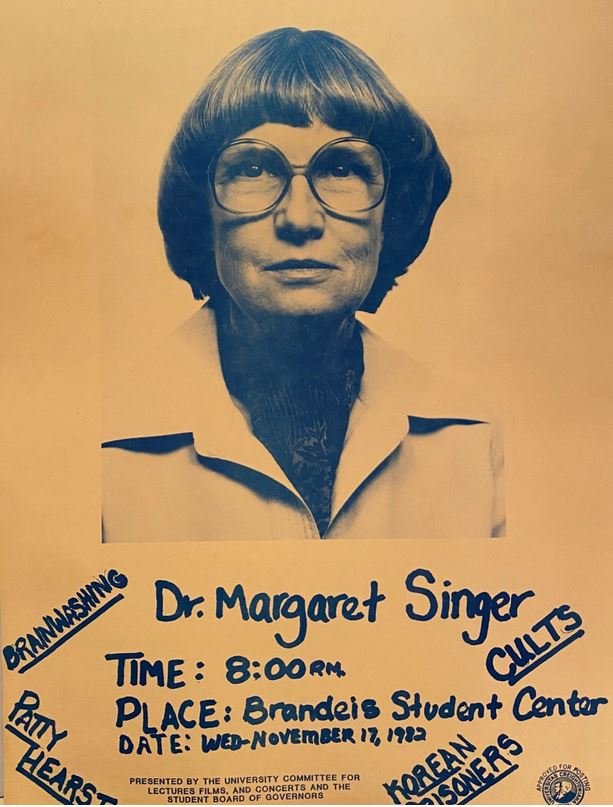

Secondly, the concept of coercive control has its intellectual roots in, among other contexts, the contentious literature on coercive persuasion, which has been developed since the 1950s. While some of its ideas are accepted within the academic mainstream, certain interpretations, drawing on dubious and discredited scholarship—particularly that of psychologist Margaret T. Singer, who was barred from giving expert testimony in U.S. courts—have been maintained in what might be called a “crude” sense and applied with little scholarly rigour to broader contexts. This was the case with attempts to expand the domain of so-called “brainwashing” to new religions during the 1960s through to the 1990s.

What appears to be happening in the Victorian inquiry is that loose ideas with origins in an anti-cult milieu, particularly those around so-called “brainwashing” and “mind control,” are being surreptitiously and/or uncritically adopted in the popular coercive control space and then communicated to the Inquiry by witnesses during the hearings.

Indeed, in recent years, several popular Australian journalistic books, and books written by former members of religious groups, have often noted how “cults,” which they rarely further define, engage in “coercive control”—though what they actually mean is not what scholars of coercive control mean by this term, but a discredited notion of “cultic brainwashing.”

Thirdly, the constellation of ideas around coercive control has proven popular amongst many scholars of religion in Australia, particularly those writing in a feminist paradigm, for understanding and critiquing various forms of what they contend is patriarchal and controlling, if not always abusive, behaviour stemming from religious doctrines. This has been particularly evident in studies relating to matters of gender and sexuality within religious groups, most notably here, various forms of male headship or complementarianism. This critique, which is currently quite widespread in the study of religion in Australia, primarily concerns evangelical and Pentecostal churches and has been taken up by sectors of the Australian media with some alacrity and conflated and confused with the problematic wider discourse around “cults.”

What makes this inquiry different from earlier inquiries is that it appears to have achieved a far greater social salience than previous government-led inquiries and may have the social momentum to lead to outcomes that are problematic for religious liberty more generally.

Victim advocate organisations and media sources like Women’s Agenda have written supportive articles, and even a few scholars of religion have voiced qualified support of this inquiry in opinion pieces—highlighting that this kind of purported “cultic” abuse occurs within various forms of Christianity, particularly, though not exclusively, evangelical and Pentecostal churches.

So, what are the problems that this inquiry might create for religious liberty?

The first problem is definitional.

The whole conceptual language around so-called “cults,” particularly the rhetoric around “brainwashing,” is unhelpful from an analytical perspective and has long been problematized by scholars of religion. This almost needs no mention in a publication like “Bitter Winter,” but to quote leading historian of religion Philip Jenkins’ 2001 book “Mystics and Messiahs”: “The word ‘cult’ has acquired over the last century or so such horrible connotations that it can scarcely be used as an objective social scientific description. It is a pejorative term used only by enemies or critics of the movement concerned.”

The adoption of the language of “cults” by the Inquiry was both inadvisable and deeply problematic; no empirical or legal distinction can be made that distinguishes a “cult” from a “religion.” Any example of this results in a form of special pleading—usually by those who consider themselves part of a religion and want to differentiate themselves from another religion they dislike, and think is a “cult.” The term “cult,” to quote a definitive discussion of this issue by legal scholar and sociologist James T. Richardson, is a “social weapon.”

Once we dispose of the deliberate and obfuscating use of the term “cult,” the reality is that this term is being used in this inquiry in a selective and often arbitrary way to target a small group of unpopular minority religions and to do this by rhetorical sleight of hand, which seeks to delegitimize their status as “religions.”

Here, the concerns raised by organisations like the legal think tank Freedom for Faith are not far from the mark—the definition proposed in the inquiry Guidance Note (which has its own historical problems) is so broad you could drive a truck through it, and on that truck you could include groups within almost every mainline Christian denomination in Australia—not to mention sectors of the Jewish, Islamic, Buddhist and Hindu communities. We have already seen the largest Pentecostal denomination in Australia, the Australian Christian Churches (ACC), labelled a “cult” in the inquiry hearings.

The second problem is related to this: to what extent does the inquiry end? And who are the actual targets of this inquiry?

From media reporting, it seems that this inquiry was intended to deal with a handful of conservative churches which were suspected of abuses and that a loose assemblage of far-right (and to a lesser degree far-left) political groups, conspiracy theorists, and sovereign citizens—who have proved disruptive and sometimes deadly in Victoria over recent years—were tacked on as an afterthought under the even vaguer rubric of “organized fringe groups.”

So far in the hearings, however, various groups have been identified in anti-cult organisation submissions and media reporting; most of which are small religious groups, many of which are churches or, in some cases, religious orders within larger churches. Some are groups we would sociologically or historically categorise as Christian sects. What is very clear from the hearings thus far, however, is that the term “cult” is being used in a very loose way to target small minority religious groups which tend to have very little in common, though a number are socially conservative, tend to have strict behavioural standards for their members, adhere to more traditional gender roles, and have stated beliefs about gender and sexuality which diverge from those held by the more progressive side of Australian politics.

There is a danger of crying wolf on this kind of inquiry, and of seeing a greater threat than exists. However, within Australia, Victoria has shown itself to be a state most willing to push through activist-driven legislation in the face of any religious opposition or concerns regarding potential encroachments on religious liberty—most notably the Change or Suppression (Conversion) Practices Prohibition Act 2021, which attracted significant opposition among more conservative sectors of the religious community in Victoria.

While Australian Federal governments have proven extremely cautious about legislating around areas which might impinge on free exercise, even when dealing with so-called “cults,” the Labor government in Victoria has shown itself willing to push ahead with legislation which is unpopular amongst some religious groups.

Moreover, much progressive political opinion in Australia is certainly not in favour of religious liberty—which it often views as maintaining entrenched Christian privilege and prejudice in Australia—and the progressive side of Australian politics has demonstrated on several occasions, going back two decades, its willingness to embrace “anti-cult ideology” against religious groups opposed to their own political and ideological interests. There is a degree of political secularism at play here, which has a decidedly anti-cult complexion, and the Rationalist Society of Australia has already been a vocal advocate for this inquiry.

What seems very clear from media coverage and the language used in the parliamentary press releases, as well as the public support it appears to have received, is that while some unpopular religious groups are clearly in the firing line, there is a much broader ambit to this inquiry, one which is likely to encompass many smaller and more socially conservative Christian churches, and perhaps even some ethnic minority faith communities.

More mainline religious groups might comfort themselves that they need not worry because they are not a “cult.” Still, the reality is that this inquiry may prove to be the thin end of the wedge when it comes to legislation that might have much wider ramifications for churches more generally, particularly those that find their beliefs at odds with the progressive side of Australian politics.

Bernard Doherty is an associate professor in the School of Theology and a research fellow in the Centre for Religion, Ethics and Society (CRES) at Charles Sturt University, Australia, based at St Mark’s National Theological Centre in Canberra. He is also an Honorary Fellow of INFORM at King’s College, United Kingdom. He has published extensively on new religions in Australia.