Japanese honor Judge Pal, who defended the principle that laws and their interpretations cannot be retroactive—a principle they did not apply to the Family Federation.

by Thomas Ward

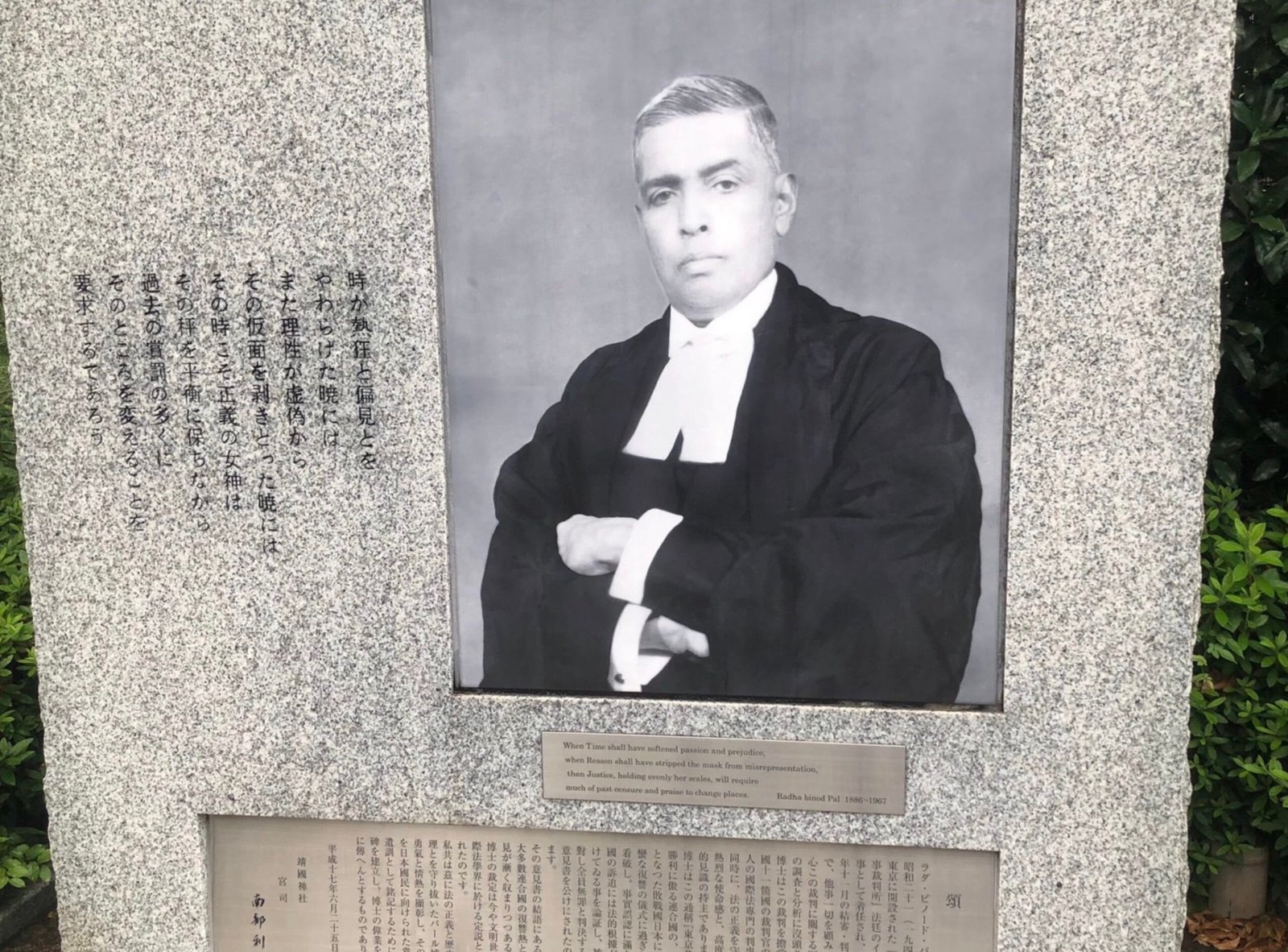

Many in Japan revere Judge Radha Binod Pal, the Indian jurist who stood alone at the 1946–48 International Military Tribunal for the Far East in advocating acquittal for all 25 defendants—senior members of Japan’s wartime government and military hierarchy. Pal challenged what he termed “Victor’s Justice”: the use of ex post facto legal theories to secure convictions. His principled dissent earned him the Order of the Sacred Treasure (First Class) from Emperor Hirohito in 1966. Monuments honor Pal in Kyoto’s Gokoku Shrine and at Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine, celebrating the judge who insisted that “nulla poena sine lege”—no punishment without pre-existing law—applies to everyone. In 2007, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in an address to India’s Parliament, honored Pal’s memory for the “noble spirit of courage he exhibited during the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.”

In his 1,235-page dissent, Justice Pal drew a sharp distinction between justice and the “manifestation of power”—the imposition of punishment by authority rather than through knowable, legitimate legal standards. He noted, with particular irony, that the U.S. Constitution twice prohibits ex post facto laws, yet American representatives endorsed retroactive jurisprudence at Nuremberg and Tokyo.

For Pal, this was not a defense of Japanese wartime conduct as such. It was a warning: even when wrongs have occurred, punishment detached from clear pre-existing law becomes something other than justice. An apparent inconsistency exists between Pal’s position, which leading Japanese LDP officials have referenced, and a precipitous reinterpretation of Article 81.1 of Japan’s Religious Corporation Act of 1951, which was relied on by Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to justify the dissolution of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification.

Following the July 8, 2022, assassination of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe by a man harboring grievances against the Unification Church (Family Federation for World Peace and Unification), media investigations uncovered extensive ties between the Family Federation and members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, triggering a national scandal and acute political embarrassment for Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s government.

On October 18, 2022, Kishida stated that he could not pursue dissolution of the Family Federation under Japan’s Religious Corporations Act Article 81 1i because, for seven decades, dissolution had been tied to criminal violations—not merely civil law violations.

Twenty-four hours later, Kishida reversed his position. A senior government official told “Asahi Shimbun” that “the prime minister changed his stance because his administration decided that it ‘will not be able to withstand the severe criticism of opposition parties.’”

Within a day, under explicit political pressure, the government’s stated interpretation shifted—setting in motion a process in which standards were subsequently applied backward to the Family Federation’s conduct from 2009 to 2022.

In March 2009, facing civil complaints over fundraising practices, the Family Federation had issued a “declaration of compliance,” and, in its ruling, the Tokyo District Court “recognized that the Church actually implemented a whole policy ‘to expand on’ the Declaration and ensure compliance with laws and regulations.” As Patricia Duval has pointed out only 3 plaintiffs “were judged to have been damaged by the payment of donations” since 2010 with the most recent having occurred in 2014. In March 2025, the Tokyo District Court, nevertheless, authorized dissolution. The Family Federation appealed to the Tokyo High Court, where the case remains pending.

One might argue that Pal’s principle cannot apply here because he addressed criminal prosecution while the Family Federation faces administrative dissolution. But Pal’s position applies not only to penal sentencing to the legitimacy of state sanction: whether punishment can be imposed through retroactive reinterpretation driven by power, rather than by predictable law. Administrative dissolution of a religious organization is an extraordinarily severe sanction—extinguishing the organization’s legal existence and potentially more consequential to religious freedom than many criminal penalties imposed on individuals.

The dissolution process raises three rule-of-law concerns:

Retroactivity. Conduct concluded over more than a decade is being reassessed under a newly expanded interpretation of what counts as wrongdoing deserving of dissolution.

Political motivation. The shift was explicitly justified as necessary because the government could not “withstand criticism”—an example of the kind of political imperative Pal warned can displace impartial legal standards.

Regulatory abdication followed by retroactive condemnation. The government had thirteen years to act prospectively. Instead, after political crisis, it condemned retrospectively.

Reports of financial exploitation connected to the Family Federation deserve careful scrutiny. If bona fide victims exist, they deserve remedies. But democracies already possess lawful tools: criminal prosecution, civil litigation, and prospective regulation with clear and stable standards rather than dissolution based on retroactive reinterpretation of the law under documented political pressure following thirteen years of regulatory silence. If legal standards governing religious organizations can be retroactively expanded once political pressure intensifies, then no religious organization can plan compliance with confidence. The vulnerability is not unique to one movement; it becomes systemic.

The Tokyo High Court confronts questions that transcend any single organization: Can regulated bodies reasonably plan compliance when the meaning of legal standards shifts retroactively? Can interpretive reversals be justified explicitly on grounds that the government “cannot withstand criticism”? Must regulators provide prospective guidance rather than retroactive condemnation?

These questions echo those Justice Pal posed at the Tokyo Tribunal. His answer was unequivocal: legitimate standards must be knowable in advance. Where state authorities impose sweeping sanctions through retroactive reinterpretation under political pressure, the process begins to resemble what Pal criticized at Tokyo—not justice, but a “mere tool for the manifestation of power” (p. 17).

Japan has honored Pal for decades. Its courts now face a test of whether Pal’s principled position still applies—three quarters of a century later—when the defendant is unpopular and the political waters are churning.

Thomas J. Ward, a Unificationist for more than fifty years, is Professor of Peace and Development Studies at HJ International Graduate School for Peace and Public Leadership. He previously served for eighteen years as Dean of the College of Public and International Affairs at the University of Bridgeport. A Fulbright alumnus, his work has been published inter alia by “East Asia Quarterly,” “E-International Relations,” and “The Journal of CESNUR.”