Political Sinicization is not the only possible or desirable form of Sinicization. A new book on Jingjiao offers an alternative.

by Massimo Introvigne

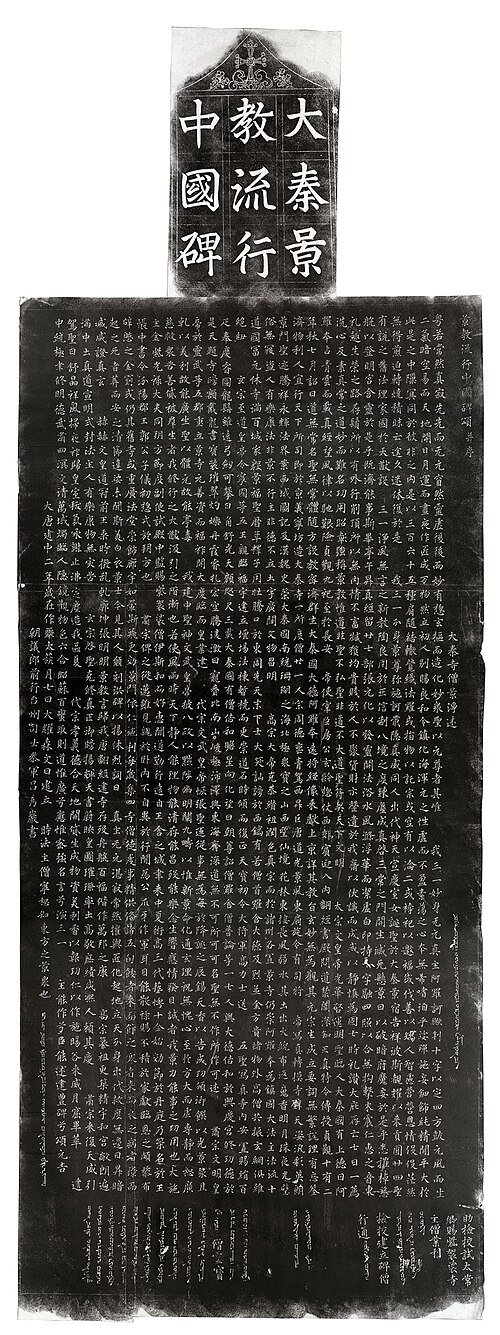

“Bitter Winter” regularly reports on the Chinese Communist Party’s campaign to “Sinicize” all religions, a policy that in practice means subordinating faith communities to Party ideology. Yet the term Sinicization has a much older and far wealthier history. Long before the CCP existed, foreign religions entering China engaged in genuine processes of cultural translation, intellectual dialogue, and theological creativity. Christianity is a prime example. When propaganda today insists that Christianity must be Sinicized because it is a “Western” faith, it overlooks the fact that Christianity was already Sinicized—deeply and successfully—more than a millennium ago. The first significant instance came through the Nestorian Church of the East, whose missionaries in the Tang dynasty created what Chinese sources called Jingjiao, the “Luminous Religion.”

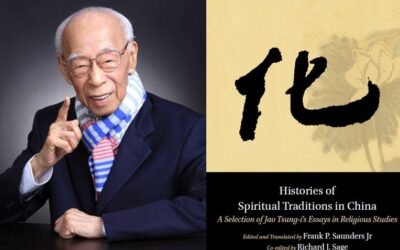

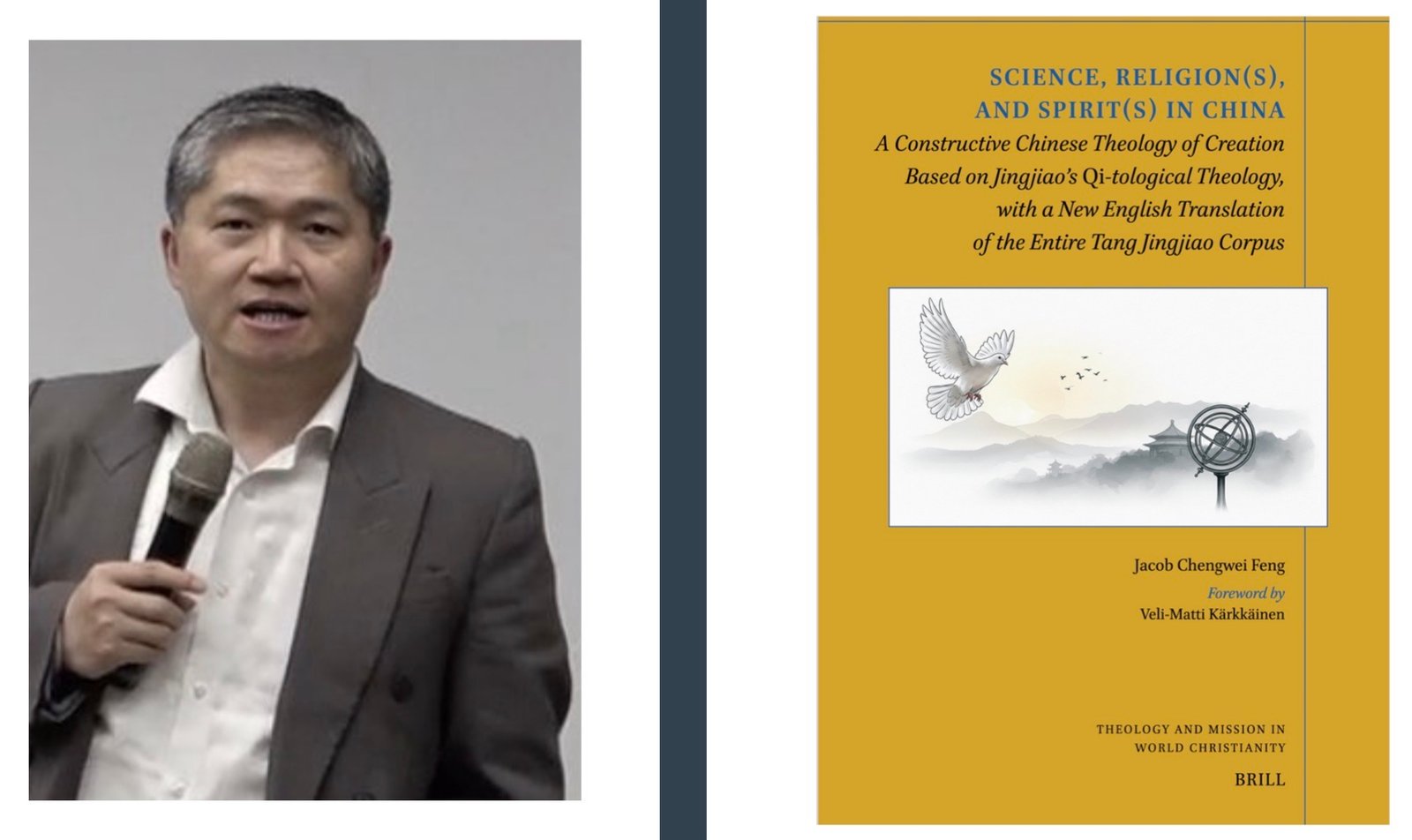

A new scholarly monograph, Jacob Chengwei Feng’s “Science, Religion(s), and Spirit(s) in China” (Leiden: Brill, 2026), offers the most comprehensive reconstruction to date of this early Chinese Christian tradition. Feng does not comment on contemporary politics and deliberately avoids present-day controversies. His project is historical, theological, and methodological. Yet precisely because it documents a genuine, premodern Sinicization of Christianity, it speaks indirectly to the way the term is used—and misused—today.

Feng’s study unfolds in two major movements. First, he reconstructs Jingjiao’s theology of creation and its missional strategy, situating both within a three-way conversation among Jingjiao, Daoism, and the scientific knowledge of the Tang period. Second, he turns to metaphor theory and develops a methodological proposal—embodied critical realism—for future work at the intersection of theology, science, and interreligious dialogue. Two threads run throughout the book: the creative use of qi as a theological metaphor, and the centrality of metaphor itself as a tool for understanding.

One of the book’s most significant contributions is an entirely new English translation of all surviving Tang Jingjiao texts. Feng aims to render these works faithfully, attentive to their Syriac theological background while sensitive to their Chinese linguistic form. Drawing on these primary sources, he shows how Jingjiao authors conveyed the foreign concept of the Holy Spirit to a Chinese audience by deploying the cosmological notion of qi—breath, air, subtle force—as a metaphor for the Spirit, while remaining rooted in their East Syriac training. Along the way, he identifies other key metaphors, including Chinese renderings of the Triune God, and argues that Jingjiao authors continued the tripartite anthropology of the Syriac Fathers.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the book is its reconstruction of Jingjiao’s mission strategy. These monks did not depend on imperial favor or political patronage. They relied instead on science, craftsmanship, and dialogue. Their training in the Schools of Edessa and Nisibis equipped them with knowledge in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy—skills that earned them respect at the Tang court and among Daoist scholars. Their mission unfolded through monastic witness, scientific expertise, courtly service, and interfaith dialogue, a form of cultural integration that was intellectually grounded and spiritually confident.

Feng devotes a rich chapter to the triad between Jingjiao, science, and Daoism, arguing that Daoism was the most suitable dialogue partner because of its positive stance on technology and its profound engagement with qi. The two traditions shared metaphors, symbols, and even cosmological structures, though their aims differed: Daoism sought immortality, while Jingjiao sought theosis and regarded the Spirit as the source of life. Despite these differences, the conversation was meaningful and produced a genuinely Chinese Christian theology.

From this historical reconstruction, the book moves to metaphor theory and introduces embodied critical realism as a method for theology–science dialogue. Readers interested in cognitive linguistics will appreciate this section, but even non-specialists will grasp the central insight: metaphors are essential tools for understanding. If qi is the fundamental metaphor in Chinese cosmology, it is both natural and theologically fruitful that Jingjiao used qi to speak of the Holy Spirit. The final chapters extend this insight into a constructive proposal for a Chinese theology of creation today. Feng develops a trinitarian vocabulary rooted in Chinese tradition—Tianzun (Honored One of Heaven), Yishu (Mover of the Sun and Moon), and Tianzun Qi (Qi of the Honored One of Heaven)—and even relates qi to the scientific concept of a field, suggesting ways the Spirit might be understood as dynamically present in creation.

Although Feng himself avoids political commentary, his work inevitably raises questions relevant to current debates. The CCP’s version of “Sinicization” demands ideological conformity and Party supervision. The historical Sinicization documented in this book was something entirely different: a creative, dialogical, and intellectually confident encounter between Christianity and Chinese civilization. Jingjiao monks did not “submit” Christianity to political control. They translated it, enriched it, and made it genuinely Chinese. Their theology of qi, their metaphors for the Spirit, and their engagement with Daoism and Tang science show that Christianity has already taken Chinese form—without coercion and without losing its identity.

Jingjiao disappeared as an organized presence in the 14th century, but its legacy remains. By recovering its texts, metaphors, and intellectual strategies, Feng’s book reminds us that Christianity has been part of China’s cultural landscape for more than a thousand years. It also shows that genuine Sinicization—rooted in dialogue rather than domination—has already happened. That historical memory is worth preserving, especially at a time when the word “Sinicization” is being redefined for political ends. Non-political Sinicizations remain possible—and better—alternatives.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.