The second annual Global Human Rights Defence’s Human Rights Film Festival in The Hague presented the sufferings of Tajik, Yazidi, Ahmadi, Pakistani, Uyghur, and other women.

by Marco Respinti

It is bitterly ironic that, while one of the latest frontiers of political correctness makes Westerners aphonic to the point of not even being able to define a woman, women in too many countries live horrendous situations. Quite aware of the problem, Global Human Rights Defence (GHRD), an NGO chaired in The Hague, The Netherlands, by Sradhanand Sital, and directed by Lina Borchardt, dedicated the second edition of its annual Human Rights Film Festival to the female condition throughout the world.

I attended the event on June 30, 2023, at the Pathé Buitenhof theater in central The Hague. Out of the several short movies and films that were presented, I review those that specifically concern the core business of “Bitter Winter,” religious liberty.

“Farangis,” a documentary by Tajik director Lolisanam Ulugova, discusses the true story of a dancer, Farangis Kasimova, 25, prima ballerina at the State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre of Tajikistan Sadriddin Ayni. She tries to overcome the prejudices of the society she lives in, which considers as morally corrupted women who pursue her profession. It may seem a marginal topic for “Bitter Winter,” yet it is not. In fact, the movie addresses a key point, both philosophical and practical: the tension between social customs framed by religion and personal freedom. Farangis faces her problems in a country, Tajikistan, that is more than 97% Islamic, but the reflections that the movie prompts apply to any society where traditional values are (still) strong.

With intelligence and even delicacy, Ulugova avoids blaming traditional cultures per se, but at the same time does not refrain from advocating individual rights. Of course, the movie cannot propose an easy solution—for the simple fact that these dilemmas have no easy solutions. All solutions must in fact be prudential, because intellectualizing on these subjects can do more harm than good. Nonetheless, the documentary makes an unquestionable point in affirming that, while preserving traditions is a worthy endeavor, one should always discriminate between what really deserves to be conserved and what can instead go.

This may remind the Western public of Irish philosopher and statesman Edmund Burke (1729–1797), who based his traditionalist philosophy on the idea that attitudes that have proven wrong must be abandoned for the sake of what is truly worthy. So, he argued, to avoid revolutions and search for a decent society, changes and reforms are as vital as conservationist instincts. Of course, Burke played on the very nature of tradition, which, as its Latin etymology makes clear, means transmitting values from one generation to another, not latching on customs that have become empty shells. “Farangis” may serve as an apt reminder of this.

A different scenario is depicted by “Yazid Girls: Prisoners of ISIS.” This is a 2016 production by Reber Dosky, a Kurdish filmmaker residing in the Netherlands since 1988. It paved the way to Dosky’s new and longer documentary, “Daughters from the Sun,” which premiered in The Hague on March 25 this year. Cemila, Ilham, and Perwin, at that time 15, 17 and 18 respectively, were among the women saved by Kurdish Peshmergas in early 2016 after the self-styled Islamic State (IS or ISIS) had militarily occupied the province of Sinjar, in Iraqi Kurdistan, in August 2014. That region was inhabited by Yazidis (also spelled Yezidis). They are members of a religious community that, alongside Christians and Shiite Turkmens living in the area, is regarded by ISIS as composed of infidels to be savagely tortured and brutally killed.

In that region, ISIS abducted more than 6,000 people and put them to work as slaves. It reserved for the women the infamous condition of sex slaves. In the short movie, Cemila, Ilham, and Perwin tell their stories on camera for the first time, detailing the horrors that Yazidi girls and women of any age and condition suffered until liberation came. ISIS’ actions have been labelled as genocide. A film like Dosky’s effectively underlines that, even if strongly reduced in numbers and strength, ISIS still performs its evils where it is still in control.

Another important tile of this mosaic of widespread female sufferance is described in “Section 298,” by directors James Dann, English, and Mahshad Afshar, Iranian. The title of the movie refers to the section of the Pakistani Criminal Code that forbids Ahmadi Muslims even to call themselves Muslims, since many non-Ahmadi Muslims consider them heretics. The snippet of “Section 298” presented in The Hague (the complete final form of the movie is due later in 2023) was enough to illustrate the constant climate of threat and intimidation that Ahmadis suffer in Pakistan. Not only many Sunni mullahs and activists criticize their theology, but the state itself acts as the religious referee while at the same time it is one of the two teams on the playing field—the strongest.

The intolerance against Ahmadis in Pakistan is a story of continuous aggressions, attacks, violences, desecrations, and killings. Dann and Afshar’s original approach is to tell this sad and known story through the eyes of women, those who suffer the situation with a double layer of depth. As Ahmadis, they suffer the fate all “infidels” must suffer in an Islamist state/society that makes discrimination (religious and other) its rule. As women, they suffer the fate all women must suffer in an Islamist state/society that considers women second-class citizens. Being Ahmadis and women in Pakistanis is the worst possible combination.

Jürgen Schaflechner, research group leader at the Department for Social and Cultural Anthropology in the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, also presented a snippet of his 2016 “Thrust into Heaven,” which shines a light on the tragedy of forced conversions in Pakistan. With the eye of the scholar combined with that of the filmmaker, Schaflechner set his camera on the situation of young girls, mainly Hindu and Christian, who are forcibly converted to Islam to justify their equally forced marriage to older Muslim men. Many incidents depicted in the movie show the reality of what some Islamist clerics instead describe as a happy and free choice to change religion. The faces and the eyes of young girls obliged to recite a false story of voluntary conversion on camera tell a totally different story.

Forced conversions hit men and women as well, but young girls are the most common target. Many of them seem to know nothing of Islam, even after some time has elapsed since their “conversion,” just a few sentences in Arabic, learned mechanically by heart. Others confess, to the bewildered face of Muslim local authorities collecting their testimony, that they do not even pray, thus violating one of the pillars of Islam, simply because they do not know how to pray according to the ways of their new faith. Schaflechner’s camera even catches some converts receiving money from Islamic local authorities. While converts testify that they never receive money in payment of their change of faith, banknotes seem to be passed onto them as a reward for their conversion.

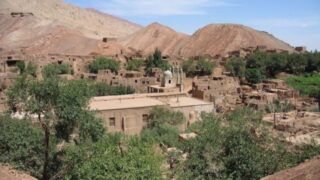

During the concluding roundtable that followed the screening of the films, Rubina Greenwood, Chairwoman of the World Sindhi Congress, criticized Schaflechner’s movie, denouncing the situation as far worse than depicted. Other panelists added important comments and evaluations on the general topic of the Festival: Manel Msalmi, International Affairs Advisor at the European Parliament; Yulia Koval-Molodtsova, responsible for Programme Development and Public Affairs at AFEW International; Herma Kluin, private detective and winner of the Women of the Year award; journalist María Luz Nóchez of Shelter City Program of Justice and Peace; and Zumretay Arkin, Program and Advocacy Manager of the World Uyghur Congress (WUC). Dolkun Isa, President of the WUC and special guest at the event, took the floor to introduce Kalbinur (also spelled Qelbinur) Sidik. An Uzbek survivor of one of the “re-education” camps that the Chinese Communist Party maintains in Xinjiang (which its non-Han inhabitants call East Turkestan) for Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities (most of which are Muslim), she was forcibly sterilized and witnessed the same humiliating persecution and the atrocities perpetrated against dozens of other women.

While GHRD announced that its third Annual Film Festival, scheduled to take place in The Hague in mid-June 2024, will focus on human rights and children, yet another production deserves an analysis. It is GHRD’s own new documentary “What Happened? The Liberation of Bangladesh”—an original production for the June 30 festival. It will be reviewed separately in a subsequent article.