Even the usually cautious United Nations has now issued an official statement suggesting Beijing may be guilty of “enslavement as a crime against humanity.”

by Lopsang Gurung

The idea that forced labor in Tibet and Xinjiang (which its non-Han inhabitants prefer to call East Turkestan) is a Western invention has finally met an authority it cannot silence. A coalition of United Nations Special Rapporteurs and Working Group members, independent experts appointed to investigate abuses without bias, has issued a statement that dismantles years of denial and is being circulated underground, challenging Beijing’s digital surveillance in Tibet and elsewhere. They are the UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, Tomoya Obokata; the Special Rapporteur on minority issues, Nicolas Levrat; the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Alexandra Xanthaki; the Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, Siobhán Mullally; the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; and the Working Group on Business and Human Rights. Together, they form a tribunal of conscience. Their verdict is devastating.

Their statement describes “a persistent pattern of alleged State-imposed forced labor involving ethnic minorities across multiple provinces in China,” a pattern so severe that “in many cases, the coercive elements are so severe that they may amount to forcible transfer and/or enslavement as a crime against humanity.” The UN experts indict the world’s second-largest economy, using the most authoritative human rights mechanisms.

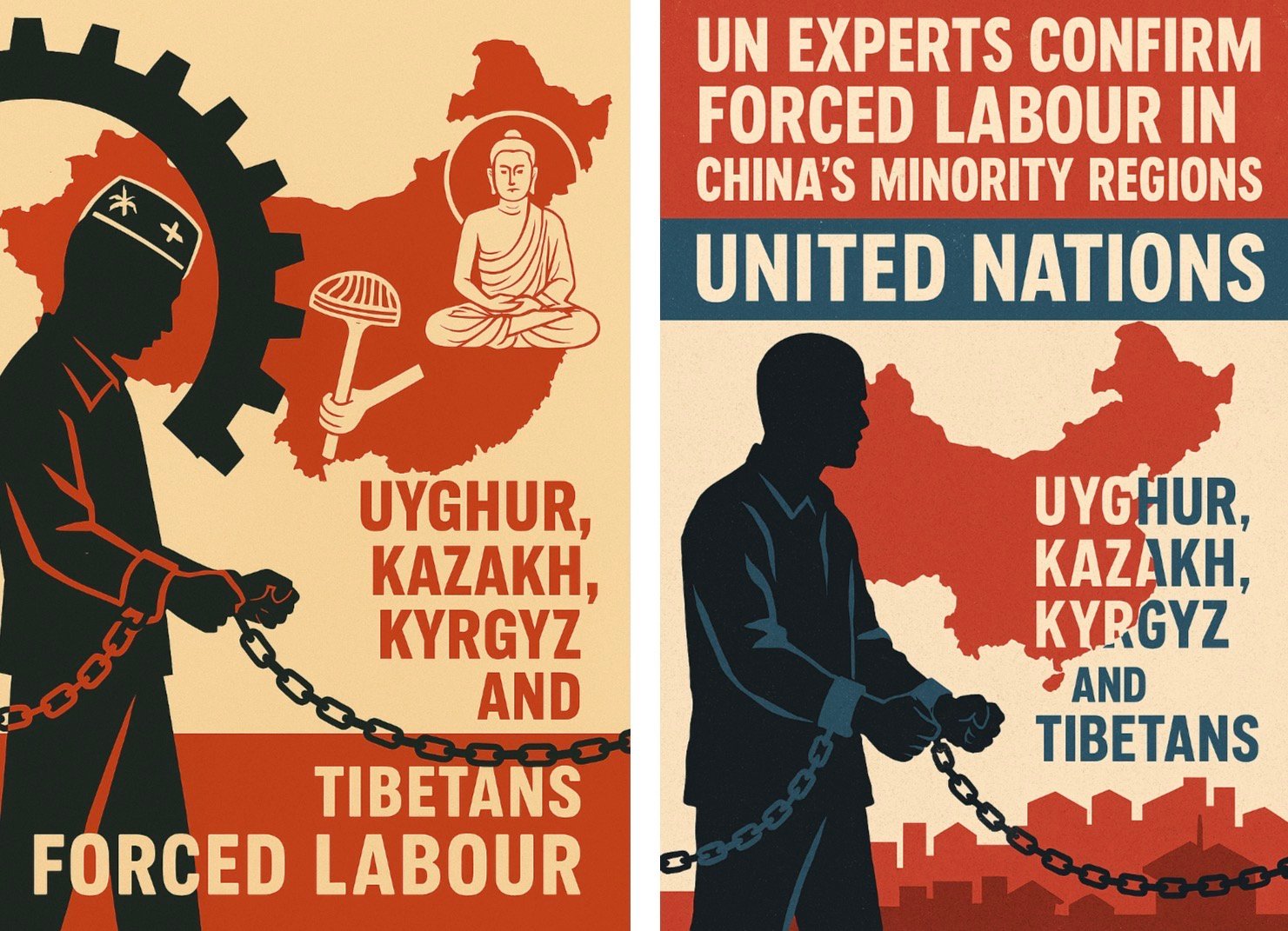

For years, Beijing’s defenders insisted that testimonies from Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Tibetan survivors were fabrications, that satellite images were misinterpretations, and that leaked documents were forgeries. They mocked the evidence as “Western propaganda.” But now the United Nations—an institution they once claimed as the ultimate neutral party—has confirmed the core truth: China’s labor transfer system is coercion on a massive scale.

The experts detail how State-mandated “poverty alleviation through labor transfer” programs force minorities into jobs they cannot refuse, under such close surveillance that rejecting an assignment becomes unthinkable. Xinjiang’s own five-year plan projects “13.75 million instances of labor transfers,” a number that highlights the absurdity of claiming voluntariness. When millions are “transferred,” choice becomes statistically impossible.

Then there’s Tibet, a region Beijing prefers to keep hidden. The experts warn that “the number of Tibetans affected by labor transfers in 2024 is estimated to be close to 650,000,” facilitated through military-style training and pressure campaigns that leave no room for dissent. Entire villages are being uprooted through “whole-village relocation,” a process that relies on “implicit threats of punishment, repeated home visits, banning of criticism, or threats of cutting essential home services.” Between 2000 and 2025, “some 3.36 million Tibetans have been affected” by programs designed to dismantle nomadic life and replace it with State-engineered dependency.

This is an Orwellian project of social re-engineering. It is the forced remolding of identity under the guise of poverty alleviation. As the experts warn, for both Uyghurs and Tibetans, these policies “forcibly change their agriculture-based or nomadic traditional livelihoods by displacing them to locations where they have no choice but to pursue wage labor,” resulting in the erosion of “language, chosen communities, ways of life, as well as cultural and religious practices.” In other words, this is cultural destruction by administrative decree.

The implications go far beyond China’s borders. Goods produced through forced labor are entering global supply chains, often cleaned through third countries. The experts issue a blunt warning to international business: “Companies must ensure their operations and value chains are not tainted by forced labor.” The demand is based on the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. It comes with a renewed call for something Beijing has consistently refused: unrestricted access for independent UN human rights mechanisms.

This is the moment when the denialists’ last refuge falls apart. Now the UN has spoken, and it has done so with undeniable force. The world can no longer pretend uncertainty. The evidence is overwhelming, the language clear, and the moral stakes high.

Forced labor in China’s minority regions is not a rumor, not a geopolitical talking point, not an American invention. It is a documented reality. And those who once dismissed it now must face the fact that the institution they trusted to determine truth has confirmed what survivors, researchers, and journalists have been saying all along.

The UN has spoken. The truth is no longer deniable.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.