New revelations shine a spotlight on the treatment of Uyghur Muslim women, detained for nothing more than practicing their faith.

by Ruth Ingram

Helchem Pazil will be 92 by the time she finishes her 17-year prison sentence. The 79-year-old Uyghur widow was 75 when in 2019 she, her three daughters and a daughter in law were given harsh jail terms for taking part in religious activities six years before. Her daughter Melikizat Memet was sentenced to 20 years.

Disturbing public order, providing a venue for religious preaching, and inciting ethnic discrimination were some of their “crimes.” Using Türkiye as a springboard for her non-state-approved Haj would have also been on Helchem’s charge sheet.

The mass internment of Turkic men, mostly Uyghur, has featured prominently on the world’s radar of human rights abuses in the Xinjiang region of China since 2017, when under Chen Quanguo’s new governorship, following strict orders from Beijing, more than one million people were corralled into so-called re-education camps and thousands sentenced to draconian jail terms.

But the destruction of the social and religious fabric of Uyghur society caused by rounding up large numbers of pious and often elderly women has been largely overlooked.

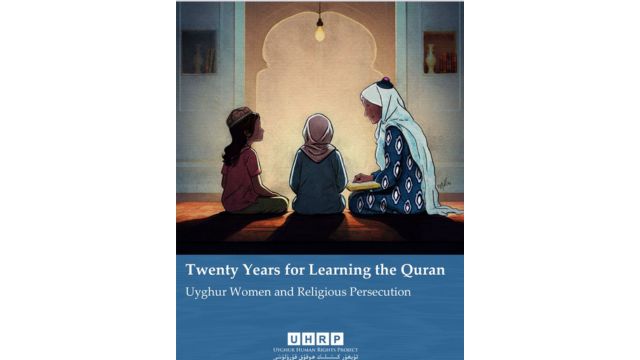

“Twenty Years for Learning the Quran” is the title of a research carried out jointly by ethnomusicologist, Professor Rachel Harris of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Norway-based Uyghur linguist and poet, Abduweli Ayup, to address the devastating impact on Uyghur society of the detentions and subsequent imprisonment of women who have historically been the linchpins of social cohesion and cultural transmission down the generations.

Caricaturing them as “baby making machines” duped by “extremist ideology” in need of re-education, is an insult to the body of respected women of faith, senior leaders of local communities, and highly educated aspirational young women, who have been herded by the state into “dehumanizing regimes of overcrowding, inadequate nutrition and sanitation, forcible sterilization and the threat of gender-based violence,” says the report.

Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) Executive Director, Omer Kanat said the report has broken new ground. “Persecution of women for practicing the Islamic faith deserves worldwide condemnation and sanctions. It is a central tool of the Chinese government’s genocide, along with sexual assault in detention, forced sterilization and abortion, and coerced marriages.”

Authors have appealed to international bodies to call out the human rights abuses levelled at these women and to address the multiple miscarriages of justice that have seen many hundreds of them languishing without trial or legal representation behind bars.

At the height of the mass internments, hundreds of religious leaders, academics, and many thousands of ordinary folks were arrested, herded into custody and according to survivor testimonies, subjected to interrogation, torture and every kind of privation.

Chen, fresh from quelling dissent in Tibet, received orders from Xi Jinping’s office to “show no mercy” in “rounding up all who should be rounded up,” in a “smashing, obliterating offensive” to “wipe out” the terrorists “completely,” and “destroy them root and branch.”

Historically Uyghur women have prayed and carried out their religious observance at home, away from the glare of men. Whilst male mosque activity was visible and more easily monitored by the government under the banner of the Islamic Association of China established in 1953, women’s religious practices within the home flew largely undetected by the Chinese state until 2009. But as Xi Jinping’s “War on Terror” gained momentum, all forms of religious study and communal gatherings, daily prayer, and modest clothing came under fire and was explicitly criminalised. “Because it was not tied to the mosque, it was linked to extremism,” noted the report.

For “crimes” such as praying when they were as young as five years old, wearing a hijab, studying and teaching the Quran, in some cases 20 or 30 years before it became illegal, Uyghur women were picked off and forced to confess to their “misdemeanours.” Some whose relatives were threatened by local police, were coerced into returning from abroad to face their punishment, as their retrospective “offences” were uncovered.

Female religious leaders known as Büwi, had gone unnoticed by the CCP for years, quietly teaching children the few Quranic verses necessary to pray, performing rituals connected with milestones of life such as birth, marriage, and death; their role vital in washing the deceased, and presiding over mourning ceremonies. According to the report they were more difficult to identify; their duties allowing them to blend into the social fabric, a role they had played for many hundreds of years.

But once “faith” became an “existential threat” under Chen, anyone who dressed modestly, eschewed alcohol and cigarettes, grew a beard or in the case of women, sported a veil or long skirt was flagged as “unreliable.”

One incident saw 91 women from a single county detained in a mass internment drive that struck at the very heart of Uyghur communities. All without exception were sentenced without a lawyer and many without the knowledge of their families. Co-author of the report, Abduweli Ayup described the arrests of women as an attempt by the CCP to “re-engineer” Uyghur communities by removing their female leaders. “Women were targeted as mothers, as teachers and as preservers of Uyghur traditional knowledge,” he said.

The Büwi craft is passed down from mother to daughter through lengthy family or community-based apprenticeships earning them a high status within their village communities. Their rituals, closely linked to Sufi traditional practices, have no need of a mosque, and thereby allow them to escape official scrutiny.

From the late 1980s, as Islam started to make a comeback across the former Soviet Union, and in China as a response to the relaxing of tight controls during the Cultural Revolution, family and community religious traditions were revitalized. Uyghur women fervently embraced the Islamic revival movements’ return to orthodox practice, scripture, and ethical self-cultivation. Many of them eagerly sought out ways to improve their religious observance by meeting to discuss sermons, study Arabic, and aspiring to study in Egypt or other Muslim majority countries.

Underground religious schools and courses sprang up through the 1990s and into the 2000s, teaching Arabic and the Quran to adults and children. A new class of female religious leader and teacher emerged, known as “Ustaz” or even “Damolla,” a term usually reserved for male clerics.

Mükerrem Ustaz, interviewed by the authors of the report, said that she combined Quranic teaching with advice on personal hygiene and described her work with children as not only teaching the Quran and prayer, but also offering instruction on ethics and manners.

Some women looked further afield in pursuit of Islamic piety, travelling to the Gulf states, Türkiye, or Egypt, and returning to the Uyghur region often critical of the Sufi-influenced styles of Islam transmitted by the Büwi. They set about promoting what in their view was “true Islam”: a return to scripture and a rejection of “superstition.”

They thought of themselves as “part of a modern, global form of Islam,” promoting “charity, community revival, and family,” according to the report.

The CCP looked on as thousands of new mosques sprung up throughout the region often paid for with Gulf money and women’s clothing increasingly turned to Saudi Arabia for inspiration, at times with tolerance but also by clamping down on illegal religious activities, and those who conducted them.

After America’s declaration of a “War on Terror” in 2001 following the Twin Tower attacks in New York, Beijing used the opportunity to single out Uyghurs, and, according to the report, to apply the label of terrorism “gradually, inconsistently and arbitrarily” to “all forms of potential resistance and violent incidents in the region.” The “everyday peaceful religious activities of Uyghur women” were suddenly under the spotlight.

A demonstration in Urumqi, the capital of the region, in 2009 that erupted into “a tragic outbreak of interethnic violence” was the “turning point in the CCP’s management of Islam in the Uyghur Region,” said the report, where “women became the direct object of government campaigns of re-education and control.”

In 2009, in a drive to rein in illegal religious activities, new Büwi were rounded up, registered, given cursory training in multiple skills that would normally have taken many years of apprenticeship, brought under state oversight, and charged with keeping an eye on local women. Older, more established Büwi were rallied for political indoctrination, but despite their certification, they were regularly harassed for “illegal” clothing and private gatherings, and their arrests continued.

Women’s religious activity continued to come under the spotlight and many, uncomfortable at leaving home unveiled, became housebound. The government’s 2014 “Let Beautiful Hair Flutter, Let Beautiful Faces Be Revealed,” drive, launched against the hijab, was indicative of deeply ingrained patriarchal and sexist views on women endemic in the Communist Party, careless of the significance of religious clothing and branding it as primitive. “It is an attitude deeply ingrained in media depictions of ‘minority women,’ one that is reproduced in gendered, commoditized encounters between Han men and minority women across China,” said the authors.

Things came to a head when in 2014, an official raid on a peaceful women’s village prayer gathering was broken up in Yarkand, in the south of the region, culminating in arrests. Violent clashes broke out as 200 husbands converged on the local police station and in the melee at least 96 were killed. Around 10,000 people were subsequently arrested from surrounding villages, according to an eyewitness interviewed for the report.

More clashes followed around the province protesting aggressive policing, but these were labelled by the government as terrorism, promoting further crackdowns on religious observance. Passports were recalled, Uyghurs were ordered to return to their hometowns, and surveillance cameras sprung up in their tens of thousands.

By 2017 with Chen’s policies rolled out throughout Xinjiang and the net tightening around any woman who took her religion seriously, mass arrests were ordered. The Xinjiang Police Files’ accounts of 408 women who were the subject of the research, mostly farmers from Konasheher county in the south of the region, revealed a string of “crimes” ranging from organising a wedding without music, wearing the “jilbab,” going on an unofficial Hajj, and displaying a poster decorated with Quranic verses. Many of the “offences” were historical and committed sometimes decades before the activities were criminalised.

Tursungul Emet was sentenced to 11 years for studying the Quran with her mother in 1974 for five days, aged five or six.

Patihan Imin, aged 70, was sentenced to six years in prison in 2017. Meticulous documentation of her misdemeanors revealed she had studied the Quran between April and May 1967, worn a jilbab between 2005 and 2014, and kept an electronic Quran reader in her home.

Between 2016-2017, 200 Uyghur women, legitimately studying Arabic and Islamic Studies at Cairo’s Al-Azhar University were forcibly repatriated to China with the cooperation of Egypt’s Interior Ministry. All the women were detained the moment they set foot in their homeland.

Authors found that no detail was spared in the scrupulous recording of state “suspects.” How often they turned off their phone, details of their hotel visits, flights taken, the frequency of leaving and re-entering China and whether or not they had a driver’s license or had visited a foreign country, were monitored.

Not only were women detained or sentenced, but some were released after their “rehabilitation” and coerced into recording propaganda videos, asserting claims that they had been “cured” of extremism. After her spell in a so-called “re-education camp,” Zülfiye Abdureşit who confessed how she had set out “on the road to extremism” pressurised by her husband’s family, became a poster girl for the CCP, and from 2019 worked as a tour guide to the camps for foreign delegations and journalists.

The ferocious and measured attack against female religious figures must stop, demanded the authors of the report. Women detained for pursuing their legitimate rights to practice and transmit their religion and culture should be released by the Chinese government, and relevant UN bodies should launch an investigation into the gender-based crimes in the Uyghur region.

“Our report provides detailed information on hundreds of Uyghur women persecuted for their religion,” said Professor Rachel Harris, a co-author of the report. “Many of them were condemned to long terms in prison for the ‘crime’ of learning a few verses of the Quran when they were children. The Chinese government has taken respected women of faith, senior community leaders, and educated young women, and subjected them to the dehumanizing regime of the region’s camps and prisons.”

“The suffering of Muslim Uyghur women is heartbreaking and necessitates the world’s attention,” said Afeefa Syeed, Senior Fellow at the Center for Women, Faith & Leadership, at the Institute for Global Engagement. “This new UHRP report lays bare the targeting of Uyghur women for imprisonment and worse, simply for practicing the basic tenets of their faith.”