Master Wang’s group is criticized by many. However, there are serious suspects the CCP uses it in Australia to promote a pro-Xi-Jinping and anti-Taiwan agenda.

by Massimo Introvigne

We all know that China hates and persecutes groups it labels as “xie jiao” (heterodox teachings), an expression it incorrectly translates as “cults” to elicit sympathy from international anti-cultists. In fact, it does more than that. One of the tasks the CCP assigns to the mammoth China Anti-Xie-Jiao Association, which likes to promote itself as the “largest anti-cult organization in the world,” is to collect and spread through Chinese media any possible item of news from all over the world, including fake news, showing that “cults” are evil and dangerous. We read often on Chinese media long articles about “cults” that never set foot in China, including NXIVM and Kenya’s Good News International Church.

Sometimes, however, “cults” are actually “used” by China as part of its intelligence and propaganda activities abroad. An interesting case is Tantrayana Buddhism, whose full name is Holy Tantra Gu Fan Mi Jin-Gang-Dhyana Buddhism, headquartered in Tasmania. Australian media have a notorious anti-cult bias, and they have recently accused the group of being a “cult,” collecting opinions supporting their theory among mainline Buddhist groups, including in Hong Kong.

As our readers know, we at “Bitter Winter” do not believe that “cult” is a valid category and do not distinguish between “good” religions and “bad cults.” I am interested here in an entirely different question, i.e., the possibility that the CCP through the United Front is using a group others call a “cult” for its own propaganda purposes.

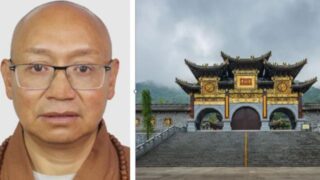

Tantrayana Buddhism emerged after Master Wang Xinde moved from Sichuan to Tasmania in 1989. A teacher of martial arts, he had been in jail for fraud and other charges (he claims that the court decisions were politically motivated; he was later rehabilitated). In 1991, he established in Hobart a school of Tantric Buddhism, which teaches a much quicker path to enlightenment than other Buddhist groups, and acquired followers in Hong Kong, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, in addition to Australia. Today, he presides over an international movement from a luxurious Victorian mansion in Taroona, a suburb of Hobart, Tasmania, equipped with a state-of-the-art museum of ancient Chinese art. Wang plans to build the largest Buddhist temple in the Southern Hemisphere in Tasmania. He anticipates the construction will take some two hundred years.

Wang is the president of the Tasmanian Chinese Buddhist Academy of Australia, also headquartered in the mansion. Among its plan is also the construction of a Tasmanian Chinese Cultural Park of Australia in Campania, Tasmania. So far, some statues have been inaugurated, with the presence of Tasmanian politicians and PRC diplomats.

Here is where problems start. Wang has given interviews where he has expressed some criticism about PRC and Xi Jinping. At the same time, its Buddhist Academy keeps links with official government-controlled Buddhism in China, and Wang has also been appointed President of the Australian Council for the Promotion of Peaceful Reunification of China, a group advocating Beijing’s view on the question of Taiwan. He has also attended events organized by Chinese diplomacy in Australia.

In 2016, Wang proclaimed that, “We will hold the latest policies enacted by the motherland [PRC] as guidance for everything we do.” He also once praised a visit by Xi Jinping to Russia claiming that “China and Russia share common values: uphold justice, promote fairness, keep peace.”

When he is accused of working for the United Front or the CCP, Wang vehemently denies it. However, when anti-cultists accused Tantrayana Buddhism of being a “cult,” the cat came out of the bag. According to Australian ABC News, “Mr. Wang refuted the claim that his group is a cult, and at the same time cited the relationship between the Holy Tantric group and the Chinese Communist Party as evidence of its legitimacy. ‘Is it possible for a cult to hold a joint meeting with the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in Beijing? Will the Communist Party accept a cult?’ Mr. Wang said.”

The answer is, of course, yes. The Communist Party would certainly use what it would, in other contexts, call a “cult” for the devious purposes of its propaganda.

It is difficult to disagree from the conclusions of the authoritative Czech research institute Sinopsis that in 2022, commenting on the case of Wang and his movement, wrote that “By offering politicians an easy shortcut to an image of minority engagement, such CCP-linked Buddhist entities allow the Party to effortlessly associate politicians and elites in democratic countries with figures whose public views they would normally find politically toxic.”