Alchemy acquired an increasingly important role in the works of the Surrealists. It was more than a symbol.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

I continue with this second article the publication of a slightly revised transcript of my comments in a walk through the exhibition “Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity,” open until September 26, 2022 at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. The comments are from a documentary by La Società dello Zolfo, which to fully grasp the sense of the narrative I recommend watching.

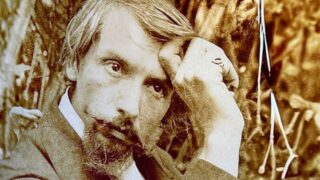

One room in the exhibition is devoted to Kurt Seligmann (1900–1962), a Swiss artist from Basel, who published a book that became particularly influential on the Surrealists, “The Mirror of Magic,” in the United States in 1948. In his painting “Baphomet,” those interested in esotericism will have a little trouble recognizing the main character with his arm raised—that is, unless they know the title of the painting.

It has passed through a transfiguration typical of Surrealism, but it is precisely the image of the Baphomet from the book by Éliphas Lévi (1810–1875) “Dogma and Ritual of High Magic.” We are, of course, still in a Surrealist world, in which Éliphas Lévi’s Baphomet for Seligmann becomes an invitation to go beyond reality and, as Breton would have said, “make the unknown known.” It is about exploring dimensions, be they simply unconscious or genuinely preternatural or supernatural, that go beyond what rationalism or everyday life proposes.

The exhibition then returns to Leonora Carrington with a statue she exhibited as “Cat Woman,” which may look like an allusion to the comic book character but actually refers to the Egyptian fertility goddess Bastet. Ten years had passed since the end of her relationship with Ernst, and Carrington lived in Mexico. There, she experienced a moment in the history of Surrealism in which the transition from esotericism as metaphor to esotericism as a plexus of beliefs upon which one commits one’s life was realized.

What happened was an encounter with the theories of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866?–1949) through Pyotr Demianovich Ouspensky (1878–1947), and through Rodney Collin (1909–1956) in particular. Two female artists who were friends, Remedios Varo (1908–1963) and Leonora Carrington, entered a path in which esotericism also presupposed becoming part of esoteric structures, in this case those of the Gurdjieff-Ouspensky tradition. This was a significant step.

In the beginning, as Breton had said, esotericism was a game from which the supernatural and spirits had to be removed for the game to work. Here, however, by dint of playing with it, the supernatural really returned, and in this second period of Surrealism we see artists embracing esotericism to the point of becoming members of esoteric movements.

Among the lesser-known female artists of Surrealism, the exhibition offers us a few pieces by Dorothea Tanning, who was Max Ernst’s fourth wife, perhaps less well-known than the artist’s other two companions presented in the exhibition, Leonora Carrington and Peggy Guggenheim. Through Dorothea Tanning and other women artists, including Leonor Fini (1907–1996), the curator wants to highlight the importance of women in Surrealism, and also in magic: women as the custodians of a privileged relationship with the magical and esoteric dimension.

At one point, however, the visitor is confronted with a painting that seems to come out of the path, one of René Magritte’s (1898–1967) versions of “Black Magic.” This seems like an anomaly because Magritte had less contact with the world of esotericism than other artists represented here. But it is also true that Magritte gives us one of the most famous and most spectacular depictions of the relationship between women and the magical dimension.

Indeed, we literally witness the transfiguration of the flesh—of female flesh, which becomes sky. However, the title Magritte gives to this work is “Black Magic,” a title that perhaps shows how the artist did not want to embrace the world of esotericism, or was even a little afraid of it and wanted to keep a certain distance.

We have seen how Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo encountered the world of the Gurdjieff-inspired groups in their Mexican period. Much earlier, however, in the 1930s in Paris, two Latin American Surrealists, Wilfredo Lam (1902–1982) from Cuba and Roberto Sebastián Matta (1911–2002) from Chile, were reading Gurdjieff and possibly had some contacts with his disciples. Lam represents a special case because he feels deeply connected with the traditions of his homeland, Cuba. He combines the Surrealist fascination with magic with that of Afro-Brazilian cults, particularly Santeria. The title of Lam’s work “Zambezia, Zambezia” also alludes to the African traditions that slaves had brought to Cuba.

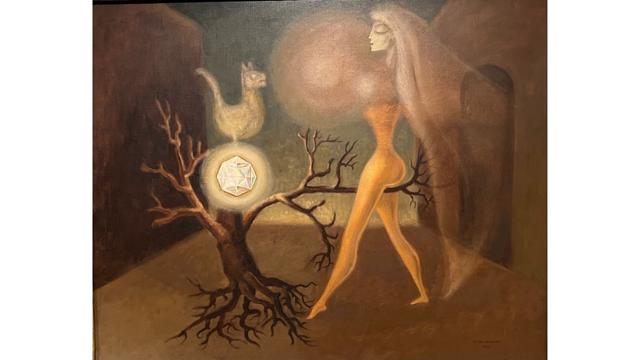

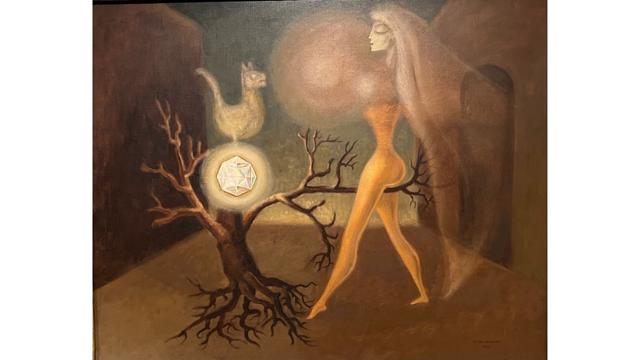

In my opinion, along with Brauner’s “The Lovers,” to which we will return, one of the most significant works the exhibition offers us is Leonora Carrington’s “The Pleasures of Dagobert.” There are many intersecting themes here. There is the legend of the French King Dagobert I (603-639), presented as a kind of Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798), but with some irony.

Dagoberto advances on a somewhat operetta or carnival float pulled by a child. However, what would seem to be a picaresque or erotic tale becomes instead an alchemical journey, an adventure of conjunction between man and woman that becomes sacred eroticism: alchemy, but a form of internal alchemy that leads us toward enlightenment through sexuality. The painting is a microcosm, presenting to us the entire alchemical journey.

In the same room, the exhibition returns to Victor Brauner, with a painting called “The Philosopher’s Stone.” The itinerary invites us to dwell on the date of this painting, which is very important. It is from 1940. In 1938, Brauner, finding himself in the middle of a fight between two men throwing objects at each other, lost an eye. Brauner had often painted monocular characters and had had strange premonitions about the importance of one-eyed people.

In 1938, when this misfortune befell him, he became convinced that the preternatural world existed, and had sent him messages foretelling him that he would lose an eye. Not only did Brauner believe this, but so did many of his Surrealists friends, who began to become convinced that magic is not just about metaphors or a beautiful language of the unconscious: occult forces and unknown energies exist.

Before the famous incident of 1938, although there were exceptions, most Surrealists followed Breton’s approach to magic, conceived as a metaphorical language that should be freed from the superstitious belief in that “imaginary host” represented by deities or spirits.

After 1938, the idea prevailed in many Surrealists that something in magic was “true,” and it is was worth the while to search for masters, for example in the Gurdjieff tradition, who might have something to say about this occult world.

We will see more examples of this in the third article in the series.