Female MISA students would say they are not feminists. But perhaps they are, in their own unique way.

by Susan J. Palmer

Article 6 of 6. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, article 4, and article 5.

Several women spoke of how they applied Bivolaru’s teachings on Tantra in their professional life. B., for example, teaches “esoteric Tango”: “I teach a course with my lover on Argentinian Tango. We focus on the polarity aspects of Tango; how men behave, how women behave. We say, ‘Don’t think what it was, what will be, just give yourself to the dance.’ After a few months, the woman learns to abandon herself. And this is what a woman does in Tango, she just follows. When [my lover and I] have a tension, we often try to apply principles from Tango to our relationship. Sometimes I say to him, ‘Please behave like we were dancing.’ Like he must be in control of the situation and take care of me. So, there’s a Tango philosophy that you can live by. We study with an Argentinian teacher, and everything that I tell you now was so natural to him that it was not a philosophy, but for us it is. There is a similarity between Tango and Tantra, because Tantra is all about this game of polarity between men and women and how we need to learn to love each other… and if we learn each other’s languages, we will be happy and reach harmony.”

H. is a psychotherapist who applies the principles of Tantra in counselling couples: “In my work [there is a focus] on sexual dysfunction, and most [couples] come to me because their desire, their attraction, is low and they want to improve their connection. When sexual attraction fades, there are a lot of conflicts in their relationship, and often their erotic life depends on their emotional life as a couple. I try to understand about the polarization, that some women are not so feminine, and they are taking on a lot of masculine energy… the man is not attracted so much by a masculine energy… I try to introduce elements from Tantra and yoga in my therapy work but of course I do it with a lot of care to understand. I explain to the men about the erotic amorous continence. Yes, for the men who are open, if I see that they are talented, the men who are gifted, yes, I explain to them about amorous erotic continence.”

P. is a massage therapist who integrates techniques from Tantra in her sessions with clients: “I do relaxation massage, and also erotic massage—we say ‘Tantra massage’ or ‘conscious touch.’ Well, I don’t know how to explain. It’s not strange for me, every time it’s like a blessing. Because when you see a human being naked, this is like revealing the treasures of his soul. And if the person is capable of letting go of the preoccupations of everyday life and really be there, it’s something really deep that happens.”

Swedish scholar Liselotte Frisk detects an assumption of gender inequality, both in Eliade’s writing and in the Indian tradition he writes about: “A contemporary reader notes that the emphasis, both in the Tantric scriptures and in Eliade’s interpretation, is on the male as a subject… Nothing similar is, however, said from the woman’s perspective. It seems that the female is considered a tool for the male; the male is the subject, and the woman is the object.”

In contrast, Frisk finds that in the contemporary writings on Tantra by Mihai and Adina Stoian, issuing from Denmark’s Natha Yoga school, “there is in the texts as much emphasis on the female experience as on the male one.”

Reports in the mass media claim that Gregorian Bivolaru forces his female students (via “brainwashing”) to participate in various MISA-run pornography industries.

Ironically, Bivolaru’s view of pornography is totally negative. Bivolaru condemns “the stupidity that transpires from [pornographic] films” as “immense and surprising,” and despises the behavior of porno actors as “far inferior to how the animals are mated.” He predicts that “the erotic revolution will throw into trash the entire history of audio-video pornographic works that currently exist on this planet. There can be no doubt about this.”

Pornography was a major divisive issue in the feminist movement. Wiccan feminist spirituality embraces sexuality in its many manifestations as life affirming and linked to the deities. Since the 1970s, same-sex unions, sex-play, polyamory, ritual sex, etc. were encouraged (or at least tolerated) in Wiccan covens, so long as they conformed to the Wiccan Rede: “An’ ye harm none, do what ye will.” But in the early 1980s, historians of America’s sexual revolution (1968–1975) began to write about the “feminist sex wars.” The American women’s movement had split into two warring camps; the “sex positive” versus the “censure positive.” Pornography, condemned by some feminist intellectuals as a key agent of female oppression, was celebrated by others as “erotica,” a harbinger of women’s sexual liberation. A heated debate ensued over how to distinguish “erotica” from “pornography.” Jane Gerhard has examined the divisions between anti-pornography (or “anti-sex”) feminists and anti-censorship (“pro-sex”) radicals.

Bivolaru’s views align closely with the “pro-sex radicals” of feminism—except that his mission is to defend the sacred status of lovemaking rather than expand the rights of women. As for MISA’s women who have integrated his teachings on Tantra into their work life, they claim their intentions are pedagogical or therapeutic, and that erotica, unlike pornography, is aesthetically pleasing and spiritually uplifting.

Documentary filmmaker and MISA yogini, Carmen Enache, has insisted that her films (which feature nudity and erotic themes) are strictly “private ventures with friends.” A MISA yogini who works at a strip club in Bucharest explained in our interview that she incorporates Tantric elements into her striptease dance to “raise the consciousness” of the male clients and to communicate the hidden, spiritual aspects of sexuality.

By the end of my research project, I had traced in these women’s narratives the configurations of a kind of “spiritual feminism”—or “feminist spirituality.”

It must be noted that these women clearly did not self-identify as “feminists.” When asked directly, “Would you describe yourself as a feminist?” one said, “No, we are not belonging to this feminist movement, because in general feminists are fighting for equality with men.” There is no evidence that Bivolaru, an intellectual and wide-ranging reader, had any interest in feminist theory; that he had read Carole Christ, or was acquainted with New Age feminist spirituality authors such as Starhawk, Zsuzsanna Budapest, or Merlin Stone.

Even so, I find it is interesting to compare the patterns of gender and sexuality found in MISA to parallel trends in neo-pagan NRMs. These trends have been scrutinized by feminist scholars of new religions, some of whom self-identify as pagans themselves.

MISA’s relevance to the feminist movement can be argued by examining its affinities to “Second-wave” feminism. Feminist scholars have constructed a rough timeline or “genealogy” of their movement and often refer to “waves of feminism” that range from Wave One to Wave Four. The First Wave developed in the mid-19th century and lasted into the early 20th and its focus was primarily on securing women’s right to vote. Wave Two emerged in the 1960s and lasted until the early 1980s; it lobbied for equality across all aspects of women’s lives.

Second-wavers moved beyond Wave One’s strictly secular focus by promoting leadership roles for women in the mainstream churches, to end “patriarchal religious hierarchies”; and by exploring alternative “Thealogies,” pointing towards ancient goddesses as inspirational symbols of feminine divinity. Second-wave feminism is characterized by a strong feminist spirituality movement that ushered in goddess-centered beliefs and rituals. These included the worship of ancient monolithic Mother Earth goddesses, or goddesses with son/lover consorts. In the Gardnerian Wiccans’ Great Rite, a High Priestess and a High Priest invoke the Goddess and God to possess them before performing a ritual that symbolizes heterosexual union by plunging a dagger (Athame) into the Chalice (symbol of the womb). MISA resembles these neo-pagan communities in women’s veneration of—and identification with—ancient goddesses.

There have been two conflicting views among academics on the plight of women in new religions, each shaped by feminist perspectives. The first view focuses on the ongoing patriarchal oppression of female disciples by male charismatic leaders. The international mass media, anticult groups, and France’s governmental anticult agency MIVILUDES share this view. The second view argues that women find “empowerment” in certain NRMs that offer “thealogies” (woman-centered theologies), goddess worship, and strong roles in leadership and ritual; roles that have been traditionally denied to them in the Abrahamic religions.

But there is a third view, advanced by a small contingent of feminist scholars who have proposed a more nuanced approach. They challenge paradigms that present a false dichotomy of women as being either empowered or subordinate. Based on their fieldwork, these scholars note that their female informants have often reported experiences of empowerment inside seemingly oppressive, male-dominated institutions. They concur that power relations in NRMs tend to be more complex and unpredictable than one might expect. After examining all sides of this debate, Wiccan scholar Sarah Pike has recommended that researchers aiming for a balanced study should investigate any sexist and abusive practices found in NRMs—but that they should also pay close attention to “women’s voices”; to women’s statements about how they experience their roles and daily life in specific spiritual communities.

During this research project I have followed Sarah Pike’s excellent advice. For nine days, I listened to the voices of MISA women. If I had to choose between the first two schools of thought—“patriarchal oppression” or “women’s empowerment”—I would choose the latter. While the seven women who are witnesses for the prosecution in the Paris trial of Gregorian Bivolaru would agree with the first school, the thirty-nine women I interviewed would fit the second. Certainly, MISA women are liberated from the traditional roles of mother and wife. Do women have opportunities for leadership in MISA? It would appear so. Women design courses, conduct workshops, write women’s teaching manuals and inspirational books. Gabriela Ambăruș was MISA’s female president from 2007 until her death in November 2022.

Liselotte Frisk has noted that, since Bivolaru’s teachings are centered on the Mother Goddess, every woman who pursues this path of Tantra can imagine herself as the incarnation of Shakti, and her body exalted as a feminine symbol of the Divine. Ten years behind America’s Second-wave of feminism, in far-off Romania a yoga teacher was developing a spiritual movement in which naked yogis and yoginis meditated on the ancient deities of India and prayed to Shiva and Shakti to accept the fruits of their lovemaking.

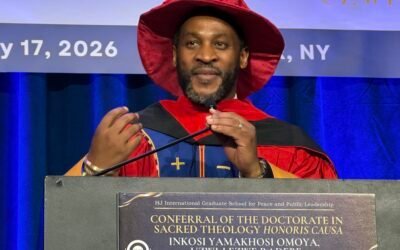

Susan J. Palmer is an Affiliate Professor in the Religions and Cultures Department at Concordia University in Montreal. She has directed the Children on Sectarian Religions and State Control project at McGill University, supported by the Social Sciences and the Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). She is the author of fourteen books, notably The New Heretics of France (Oxford University Press, 2012).