The authorities claim “women” have been “liberated” from a “sex cult.” A well-known Canadian scholar interviewed the “victims” and was told a different story.

by Susan J. Palmer

On November 28, 2023, there was a militarized police raid on a yoga school in France known as “MISA” in Romania and “Atman” in Europe. “MISA” stands for “Movement for Spiritual Integration into the Absolute”.

Just after 6 a.m., a SWAT team of around 175 police, wearing black masks, Kevlar helmets, and bullet proof vests, descended on eight separate houses, five in Paris and three located in the same yard in Nice, brandishing semi-automatic rifles. They smashed in the doors and ran up and down the stairs, shouting orders. Their targets were neither terrorists nor drug dealers. What the police were searching for were members of a “secte” (“cult” in English). They found some 95 vegetarian, non-smoking, alcohol-abstaining yoga practitioners.

On that fateful morning, most of these yogis were still in bed. A few were in the kitchen boiling water for tisane. The masked police handcuffed them, made them stand outside the house without coats or shoes in the freezing courtyard, then bussed them to the police station of Nanterre, in the Paris suburbs, and other police stations, where they were held for questioning (“garde à vue”) for up to 48 hours (there is no habeas corpus in France).

As co-author with Stuart Wright of a book called “Storming Zion: Government Raids on Religious Communities” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), I was curious about this raid. So, I contacted MISA’s administrators and arranged to visit their yoga school in Bucharest, where several of those released with no charges had returned (others went to their respective countries, other than Romania, and some remained in France). Among the six who are being detained in different prisons of the Paris area on charges related to “abuse of weakness,” rape, kidnapping, and human trafficking, is Gregorian Bivolaru (b.1952), MISA’s co-founder and spiritual teacher.

I flew to Bucharest on January 7, 2024, and interviewed twenty-five Romanian yogis, all students of MISA, 14 of whom were caught in the French raids, over nine days. The interviews were conducted in English and occasionally in French, with the help of an interpreter for those who spoke only Romanian. Their ages ranged from 27 to 72, and their professions and occupations were quite varied.

There are two aspects of the raid on MISA that I found significant. First, the masked police team belonged to a special unit called CAIMADES. They are specially trained to deal with crimes and misdemeanors perpetrated by the “gourous” of “les sectes” (“cult leaders”) and to “rescue the victims.” Second, Gregorian Bivolaru teaches a form of sacred eroticism and he has been incorporating ancient Tantric erotic philosophy and techniques into MISA’s yogic practice for decades. From the perspective of the “cult watchers” in France’s state-sponsored anti-cult movement, these would be considered as “dérives sectaires” (cultic deviances), which must inevitably result in the “abus de faiblesse” (abuse of weakness) of Bivolaru’s “victims.” Moreover, for France’s anti-cult activists, Tantra yoga and ancient Hindu erotic practices in a “cult setting” could hardly be considered consensual. “Brainwashing,” rape, kidnapping, and human trafficking must somehow be involved.

The story of how Bivolaru, a Romanian spiritual leader and erotic mystic, came to be captured and put on trial by France’s government-sponsored anti-cult movement is complicated but fascinating. One finds three fiercely conflicting perspectives in the case.

From a feminist #MeToo perspective, one sees a powerful male leader imposing Hindu patriarchal dogma on Western female disciples to facilitate sexual exploitation and maintain a rigid gender-based hierarchy.

From the French anti-cult perspective, one sees a “guru” relying on techniques of mental manipulation to enslave his female followers in a vast, international human trafficking ring that funds his “secte.” In France a “secte” is not a “religion.” Rather, it is regarded as a kind of “bande organisée” (criminal gang).

Finally, there is the third perspective on the case shared by MISA’s 30,000-odd yoga students who view “Grieg” (Gregorian Bivolaru) as an enlightened spiritual master who has devised the spiritual path of “mystical eroticism” based on his studies of Tantra yoga in ancient Indian sources, filtered through the writings of his correspondent and source of inspiration, Mircea Eliade, one of the great scholars in the Chicago school of comparative religion.

From MISA students’ perspective, Bivolaru’s 2010 book “The Secret Tantric Path of Love to Happiness and Fulfillment in a Couple Relationship” is a practical guide for a harmonious and long-term heterosexual couple relationship. For Bivolaru’s women disciples, since his Tantric teachings are centered on the Mother Goddess, every woman on this path can become the incarnation of the goddess Shakti. MISA women explained in our interviews how through “mystical eroticism” their minds became liberated from patriarchy and their bodies exalted as feminine symbols of the Divine.

There is no time or space in this series to discuss these conflicting views on Bivolaru’s case. For those interested in this “cult controversy” and for MISA members awaiting trial, the “denouement” to this story is impossible to predict. Therefore, I will limit my efforts to exploring this complex situation within the context of France’s government-sponsored anti-cult movement and “anti-sect wars.” To this end, I will follow three steps:

1. I will present an anatomy of the raid and its aftermath. Based on the data gleaned from interviews with MISA students, I will argue that the Judicial Police violated France’s legal regime for the “garde à vue” (the detention and interrogation of suspects in police custody).

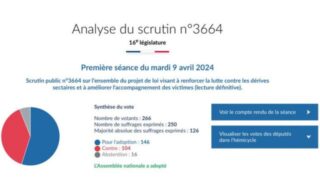

2. I will examine the role of MIVILUDES (Mission interministérielle de vigilance et de lutte contre les dérives sectaires, Inter-ministerial Mission for Monitoring and Combating Cultic Deviances) in Bivolaru’s arrest and will discuss MIVILUDES’ concept of “dérives sectaires” and its mission to control France’s “sectes.”

3. I will explain the charges of “abus de faiblesse” against Bivolaru and five MISA members within the context of France’s 2001 About-Picard law. The modus operandi of “abus de faiblesse” allegations as a “weapon” for controlling “gourous” will be explored and its implications for Bivolaru’s legal situation will be discussed.

The accounts I will present in this series of the 2023 raids on MISA and the Romanian detainees’ experiences with the French police are gleaned from the interviews that I conducted in Bucharest in January 2024 at MISA’s Yoga School. My research participants described blatantly illegal treatment by the police and a general disregard for their rights and well-being while they were being held in police custody for questioning.

Law professor Jaqueline Hodgson describes the proper procedures of “garde à vue”: “Under art 63 of the CPP (Code de procédure pénale) a police officer may place a person in ‘garde à vue’ where there is reasonable suspicion that she has committed or attempted to commit an offence and the officer considers detention necessary to the investigation. The public prosecutor (the procureur) must be informed at the start of the ‘garde à vue,’ which lasts initially for 24 hours, and her authority is required to extend the period of detention for a further 24 hours. This is the primary guarantee for the proper treatment of the suspect (…). Under art 63-1 CPP, the detainee must be informed, in a language that she understands, of the nature of the offence for which she is being held and of her rights to inform someone of her detention (under art 63-2 CPP), to be examined by a doctor (art 63-3 CPP) and to see a lawyer (art 63-4 CPP). The right to custodial legal advice was first introduced in 1993; the suspect was allowed a 30- minute meeting with her lawyer, 20 hours after the start of the ‘garde à vue.’ In 2000, this was amended to allow access to legal advice from the start of detention, but still only for 30 minutes.”