Christian critics of “cults” often argue that novels and films about Mary Poppins promote “cultic” or “occult” ideas. All is based on an old misunderstanding.

by Massimo Introvigne

One of the favorite topics of Christian conservative criticism of “cults” or “the occult” is that it is promoted through books and films that poison children with esoteric and even Satanic ideas. From the late 1990s on, the novels and movies featuring Mary Poppins, the flying nanny created by the Australian-British novelist Pamela Travers, are often at the receiving end of this criticism.

I am particularly interested in this story because I am afraid I contributed, unwillingly, to the creation of the Mary Poppins “cult” scare. The story in itself is not less extraordinary than Pamela Travers’ creature.

On September 6, 1995, La Stampa, Turin’s daily newspaper, titled at full page “Is Mary Poppins really Satan?” Many readers were, understandably, surprised but no reader was more astonished than me. In fact, I learned from the article that I had accused Mary Poppins to have “clear links with esoteric and Satanic ideas,” and with the world of “cults.” I was credited for having discovered that “under the gentle mask of the extraordinary nanny a dangerous creature is hidden, with features that clearly appear as Satanic.”

The same journalist, appropriately, interviewed a Catholic exorcist who complained that “Introvigne normally minimizes the presence of Satanism in our life,” a reference to my books and articles on Satanism where I denounced ill-founded Satanism scares. But this, for the exorcist, amounted to still more convincing evidence that Mary Poppins was really promoting Satanic “cults”: “If Massimo Introvigne has written such a thing, he said, this could only mean that the danger is really there.”

The problem was, however, that I had never written “such a thing.” The day before, on September 5, 1995, the Catholic daily newspaper Avvenire had published an article by me on Pamela Travers and esotericism that was, if anything, complimentary to the creator of Mary Poppins. This did not prevent other Italian daily newspapers from picking up the news that Mary Poppins was “a cultist” or “a Satanist.” The story was spicy enough that Italian media were quoted abroad, reinforcing an association between Mary Poppins and “cults” that persists to this day.

I wrote a letter to La Stampa, and slowly persuaded most Italian reporters that there was in fact a big misunderstanding. By September 8, the situation was improving, and another daily newspaper, Il Manifesto, wrote, appropriately, that the news was not that I had accused Mary Poppins of “cultism” or Satanism, but that a reputable newspaper like La Stampa had entirely misrepresented my Avvenire article.

Calling my article in Avvenire “original, entertaining and scholarly,” Il Manifesto commented that “Introvigne simply analyzed the cultural education of Pamela Travers” and “called for more scholarly studies about the important cultural influence of [Russian-Armenian esoteric teacher George Ivanovich] Gurdjieff in Europe.” The newspaper correctly noted that the word “esotericism” that I used for the work of Pamela Travers is not a synonym of “occultism” and much less of “Satanism,” and I never used the word “cult.”

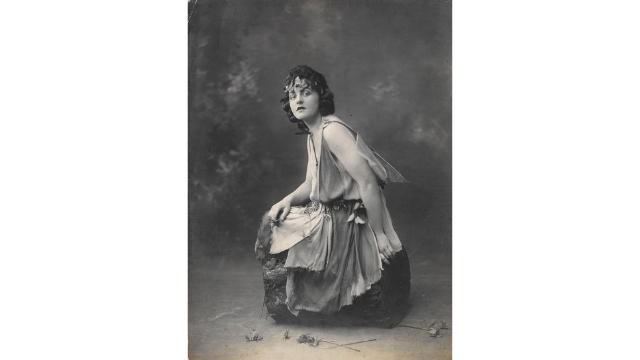

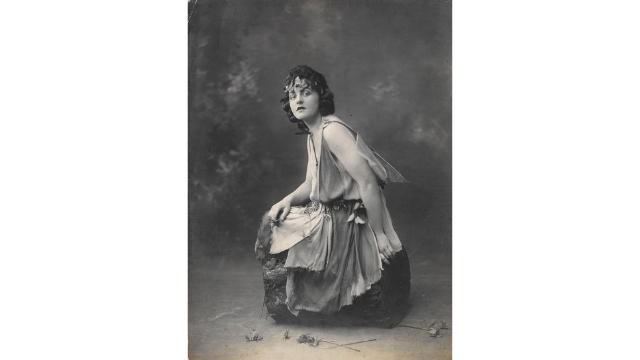

What was this all about? In 1995, I was in contact with Pamela Travers, who was 95 and will die the following year. In the end, I received some letters she dictated to her doctor, as she was no longer fit enough to write or talk herself. My interest was to hear from Travers how she met Gurdjieff and how her relationship with him developed.

As she confirmed to me, the novelist and the esoteric master met in 1938, while the first edition of Mary Poppins was published in 1934. The equally famous Mary Poppins Comes Back followed in 1935. These novels, thus, could not have been influenced by Travers’ meetings with Gurdjieff.

However, Travers admitted that some allusions to Gurdjieff, who by then had become an important reference for her, were included in subsequent Mary Poppins books, particularly Mary Poppins Opens the Door in 1944 and Mary Poppins in the Park in 1952. Travers more clearly alluded to Gurdjieff in her non-fiction works About the Sleeping Beauty (1975) and What the Bee Knows (1989), and in her non-Mary Poppins fictional work Friend Monkey (1971). Travers also wrote the entry on Gurdjieff for Richard Cavendish’ encyclopedia Man, Myth & Magic (1970), on which she based the subsequent booklet George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1973), which had a limited distribution.

One example of Travers’ allusions to Gurdjieff in Mary Poppins in the Park is when the children entrusted to the care of the nanny, Jane and Michael, discover that the distinction between our tangible “real” world and other worlds is less clear-cut than it seems. While Jane is reading to Michael in the Park the story of three princes, called Florimond, Veritain, and Amor, the princes step out from the book and start a real-life conversation with the children.

Michael tells the princes that he and his sister are “real” while Florimond and his colleagues are just characters from a book. Florimond invites Michael to touch his quite solid dagger, and admonishes the boy not to be so sure about what is real and what is not.

Of course, there can be many sources other than Gurdjieff for the idea that the distinction between the real and the imaginary world is not as obvious as it may seem. However, Travers herself stated that allusions to Gurdjieff are disseminated into her post-1938 books, and that they are “Zen parables” that one can read at various different levels.

Christian critics of “cults,” just like the author of La Stampa 1995 article, have built a syllogism: Gurdjieff was a Satanic “cultist,” the author of Mary Poppins was a disciple of Gurdjieff; thus, Mary Poppins’ stories and film promote “cults” and Satanism, and children should be protected from them.

A first answer to this is that Disney’s Mary Poppins movies do not include any of the references to Gurdjieff and his ideas one may find in the later Travers novels. These allusions are subtle, can be understood only by those who know Gurdjieff, and the Disney screenwriters did not take from the novels their more philosophical comments, not fit for movies primarily intended for children. This was one of the reasons Travers repeatedly commented that the 1964 acclaimed Disney film Mary Poppins was a good movie but one that had little to do with her books.

More importantly, Gurdjieff was not a Satanist. Some Christian counter-cultists have been misled by the title of his posthumous book, Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, but Gurdjieff’s complicated esoteric system, which is based on Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Sufism, and various brands of Western esotericism, is totally different from Satanism.

Yes, Travers had esoteric interests and regarded herself as a disciple of Gurdjieff. There are some subtle traces of this, not easy to detect for the non-specialist, in her later Mary Poppins novels—but not in the earlier ones, which are the most famous and the ones that inspired the 1964 Disney movie. Certainly this film, a masterpiece that won five Academy Awards, does not promote any “cult,” and associating it with Satanism is simply ridiculous. The same is true for Travers’ Mary Poppins novels. While her esoteric ideas may be detected by scholars in some passages, and in some of the songs she liked to include in the novels, her fiction was certainly not intended to promote them.