At a symposium in Tokyo on October 1, the case was discussed within the broader framework of different approaches to religion and “cults” in Japan and the West.

by Massimo Introvigne

“Bitter Winter” has covered from the days following the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on July 8, 2022, the Japanese controversy about the Unification Church, now called the Family Federation of World Peace and Unification. Abe was killed by a man called Tetsuya Yamagami, who claimed his mother went bankrupt in 2002 because of her excessive donations to the Unification Church. The assassin intended to punish Abe for his support to organizations connected with the religious movement.

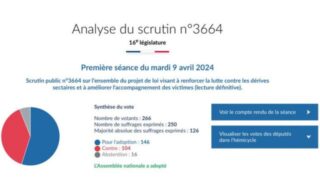

Yamagami’s statement set in motion a series of the events that led to the government’s request to dissolve the Family Federation on October 12, 2023, and the subsequent court case, currently pending.

As foreign observers of the situation in Japan, I and other scholars realized that the context of what we regard as measures contrary to the principle of freedom of religion or belief should also be understood and studied. Particularly after a religious group called Aum Shinrikyo perpetrated several crimes, including a lethal terrorist attack with sarin gas against the Tokyo subway in 1995, new religious movements, and sometimes religion in general, are perceived by many Japanese as a problem rather than as a resource.

The fact that theories about “cults” using “brainwashing” to control their “victims” have been rejected as pseudo-scientific by the vast majority of scholars who study new religious movement in the West, and by courts of law in the U.S. and other countries, does not seem to be generally known in Japan. Even the opposition by a large part of the scholarly community to the “anti-cult” narrative prevailing in the media that had manifested itself in the West did not find a parallel in Japan, perhaps because local scholars themselves were still influenced by the tragedy of Aum Shinrikyo.

For these reasons “Bitter Winter,” with the support of the Washington-based International Religious Freedom Roundtable, organized a closed-door symposium in Tokyo on October 1 for selected scholars, religious activists, and reporters, where one European and one American scholar, i.e., the undersigned and Holly Folk, from Western Washington University, offered some general reflections on the global controversy about “cults.”

Nadine Maenza, co-chair of the International Religious Freedom Roundtable and former chair of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), and Katrina Lantos Swett, co-chair of the International Religious Freedom Summit (a different organization from the International Religious Freedom Roundtable), sent video messages to the symposium.

The symposium continued with an explanation of the legal issues about the Family Federation by one of the lawyers representing it, Tatsu Nakayama (who is not a member of the Family Federation himself).

Award-winning (and Sociology graduate) journalist Masumi Fukuda discussed the campaign against the Family Federation from her point of view as a reporter who was not particularly sympathetic to the religious movement when she started investigating the case. She concluded, however, that the anti-cult campaign against the former Unification Church was politically motivated and often based on incorrect information.

The symposium was certainly informative, with Western scholars learning from the Japanese speakers details of the case they did not know—and perhaps the Japanese participants better understanding why the majority of scholars and religious liberty activists in the West oppose the anti-cult narrative about new religious movements.

The conversation continues.