Screenwriter Jan Coufal offered a one-sided reconstruction of a sensational “cult” case. He missed an opportunity.

by Massimo Introvigne

In one word, it’s bad television. I was able to watch, helped by an English translation of the script, the three-episode 2022 Czech TV miniseries “Guru,” directed by Biser A. Arichtev based on a screenplay by Jan Coufal. It is about the case of the Guru Jára Path, to which I have devoted a long article, an academic encyclopedia entry, and a series in Bitter Winter.

I have also interviewed extensively members of the Path, as well as some of their opponents. Thus, I probably know more about the Path than Coufal himself, who by his own admission has only reviewed the court records (I did, too, having received them from the defendants) and talked with the chief police investigator and the prosecutor of the case. This is already problematic, as it indicates from the very beginning that there was no interest in understanding the point of view of the defense nor, more importantly, of the members of the Path.

To understand why the miniseries is so bad, I should first summarize what the case was all about. Jaroslav (Jára) Dobeš is a 51-year-old Czech spiritual teacher, who established the first nucleus of what will become the Guru Jára Path in 1996. The teachings of the Path encompass a great number of esoteric techniques, from Tarot to astrology, but what attracted the attention of anti-cultists were Jára’s Tantric teachings about sacred eroticism.

One of these teachings is that psychic residues of past sexual relationships, “hooks” for women and “thorns” for men, seriously damage both relational life and spiritual progress. Once the “hooks” are identified, the woman should go through an “unhooking” process (men go through “unthorning” too with the help of female initiates, but for whatever reason this has not attracted controversy). Unhooking involves the sexual penetration of the women by a highly experienced Tantric guru (in the case of the Path, Jára), with sacred energy thus flowing into the woman, without orgasm or ejaculation by the master, preceded by breathing exercises performed by the woman.

In the Path’s system, not all women needs unhooking. In its heydays, the Path had some 3,000 female members. Only some 300 of them, or 10%, were counseled, or they asked, to go through the unhooking ritual. The ritual has not been invented by Jára, has a series of precedents in both Eastern and Western sacred eroticism traditions, and is difficult to understand without some familiarity with these traditions—difficult, that is, unless one reduce it to Jára’s quest for “sexual satisfaction and need for power,” which is actually a quote from “Guru.”

Sacred eroticism is a famous bête noire of anti-cultists, and in the case of the Path they were unleashed against Jára by apostate ex-members. Finally, police investigators were led to believe that unhooking might disguise rape, and interviewed more than one hundred women who had been unhooked. Eight reported their experiences had been unpleasant.

Police and prosecutors regarded the case of L.N. as the more promising. She was the daughter of a senior police officer, told her story to the police, and successfully resisted further attempts by the defense attorneys asking that she testifies in court, claiming post-traumatic stress and finally leaving the Czech Republic. She told the police she had been molested both by Jára and by his main female co-worker, Barbora Plášková.

L.N.’s story was used as justification for the October 19, 2010, raids by the Czech police, which stormed the ashrams of the movement and the private homes of some members, detaining 13 female devotees. The involvement of the media and the fact that the raids were carried out in the early hours of the morning by elite police corps, as if they were dealing with terrorists, are similar to what happened in other “cult” cases.

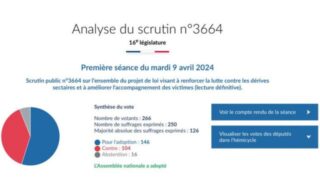

In separate trials, Jára and Plášková were found guilty for the case of L.N., where they were sentenced respectively to jail penalties of five and a half and five years, and of the other six women (the case of the seventh woman had been dropped for lack of evidence), for which however procedural rules prevented the court from imposing further jail penalties. By then, Jára and Plášková were in the Philippines, detained in unhealthy detention centers for illegal immigrants pending their appeals on requests for asylum that have so far been rejected.

Enter the movie “Guru.” We don’t see much of Jára there, called Marek Jaroš in the miniseries, except that he is depicted as a violent man who physically assaults the girl who has become his main accuser and even abuses the loyal Plášková (called Klara Pliskova), both traits untypical of the real-life Jaroslav Dobeš according to all my interviews. Besides, if Jára had beaten L.N. or one of his other accusers, this would have been used against him in the trial, and it wasn’t.

The miniseries is the story of two fictional devotees of the Path (disguised under the name Esoteria), Alice Balvínová and Kamila Kraslová. Both have been seduced by Klara to join Esoteria in difficult moments of their lives. Alice has been abandoned by her partner while she was pregnant, and struggles for the custody of her daughter. Kamila has a difficult relation with her ex-boyfriend, and is introduced into the Path by her manipulative mother Magda, who has been unhooked herself.

After the unhooking, Alice runs to the police, where a brave policewoman, against the opinion of the prosecutor, believes her. Kamila overcomes her doubts and accepts to be unhooked, pushed by her mother, but her experience is traumatic and she tries to kill herself.

This incident changes the mind of her mother Magda, who tells the policewoman how to find other women who felt raped during the unhooking. These women and Alice (but not Kamila, who according to the prosecutor in the end went to the ritual voluntarily, at least from a legal point of view) testify in court, and in the end the guru and Klara, who have both escaped to Thailand in the meantime, are sentenced to jail penalties.

We cannot expect from a fiction to be accurate, and the characters are created by putting different stories together. A detail in Alice’s story is similar to the real-life case of L.N.: she is photographed smiling after the unhooking, which is not typical of someone that has just been raped. The series, however, does not specify that, after the first unhooking ceremony, she willingly returned for a second one. Other details come from the stories of other apostate ex-members, such as the love letters they wrote to the guru.

Even for a fiction, but one that claims at the beginning to have been “inspired by real events,” the reconstruction of the court case is misleading. If Alice is L.N., as mentioned earlier, she never testified in court. Nor did she run to the police to report a rape. In fact, the eight women who became part of the court cases did not go to the police.

The police found them, based on the list of members supplied by the apostates. There was only one woman who was induced by an apostate ex-member to go to the police to testify, but it was clear that she had submitted to the unhooking voluntarily and, when in the middle of the ritual she changed her mind and did not want to go on, the ritual was interrupted. Nothing came of her case.

The first intervention of the police in the miniseries is reported as a kind encounter where both the guru and Klara are handled with white gloves by the female police investigator and the other officers. This is not similar to the dramatic raid of 2010. Speaking of trauma, and separation of mothers from children, the female Path devotees who had the experience of the raid carried out in the early morning by heavily armed elite police forces, were detained, and in several cases separated from little children, were themselves heavily traumatized, as they told me in my interviews.

There are many other details the miniseries had wrong, but the central point is how the Path’s sacred esotericism and the unhooking ritual are interpreted. One claim is that the unhooked women were selected among the “mentally injured,” thus “easier to manipulate.” This is factually false. I have interviewed successful professional women with college degrees who had been unhooked, and reported the experience as spiritually uplifting and corresponding to what they expected.

When she is concerned about Kamila, her mother Magda is reminded that she too after the unhooking “wanted to kill herself,” as if this was a normal reaction. It is not, in real-life Guru Jára Path. The women I interviewed reported the experience as exhilarating, although in the sense of a “spiritual orgasm” rather than in common sexual terms. Some reported that this status persisted for several weeks. There were cases of women who went into a depression, but this was due to the raid or to the hostility of their families when the Jára case erupted in the media rather than to the unhooking.

One woman in the miniseries insists that she had no idea what unhooking was all about, and others that they understood it only vaguely before the actual experience. This defies credibility, as the theory of the hooks and the unhooking is clearly presented in written publications of Guru Jára that everybody can read.

Of course, those who produced the miniseries would claim that my interviewees are members of the Path, while they wanted to tell the story of the “victims”—although they did not interview them, only the police investigators and the main female prosecutor, whom they converted into a male one. But here precisely is the main problem with the miniseries. There is little doubt that new religious movements proposing a path of sacred eroticism challenge some deeply held beliefs in our societies, such as that religion and eroticism are two separate spheres. A movie on one of these movements might have been a good opportunity to explore what women (and men) who join these groups really believe and experience.

Yes, the minority of women who felt abused during the unhooking should have been heard, and certainly I do not suggest that sexual abuse, if proved, should be condoned under the pretext of religious liberty. But what about the majority of Path women who told the police their experience was positive? These women were the victims of abuses too: by the police and the media who refused to take them seriously, and regarded them as brainwashed zombies.

In the end, the theory of the miniseries is simple. It is impossible that women would willingly go through sacred eroticism rituals and derive from them positive experiences. If they testified that they were victims, they are victims. If they testified that they were not victims, they are victims as well—of psychological “manipulation,” the miniseries says.

Bad television, indeed. It is bad enough to peddle the pseudo-scientific theory of brainwashing. When this is done by vilifying as “mentally injured” by definition the women (and men), in many cases highly educated and with prestigious jobs, who remained in the Guru Jára Path and insisted they had chosen to participate in sacred eroticism rituals freely and of their own will, something worse happens. Under the pretext of fiction and of “siding with the victims,” it is these women (and men) who become the victims of visual and verbal violence.