The persecuted movement has released a new yearly report about the imprisonment, torture, and killing of its members on an unprecedented scale.

by Massimo Introvigne

The 2025 annual report on the persecution of The Church of Almighty God (CAG), released on February 13, 2026, echoes similar documents the CAG has published for several years. Although the CAG itself produces these reports, “Bitter Winter” has long regarded their data as reliable. Our own continuous monitoring of Chinese media, police announcements, and public security press releases confirms the same patterns the report describes: mass arrests, heavy sentences, and the steady expansion of campaigns aimed at eliminating CAG believers. What the Church documents from inside is echoed, often unintentionally, by the CCP’s own official channels—a convergence that suggests the authenticity of the picture presented.

The new report catalogues human suffering, records state violence, and provides insight into a campaign of repression that has become vast and methodical—a campaign aimed not at delivering justice but at extinguishing a faith.

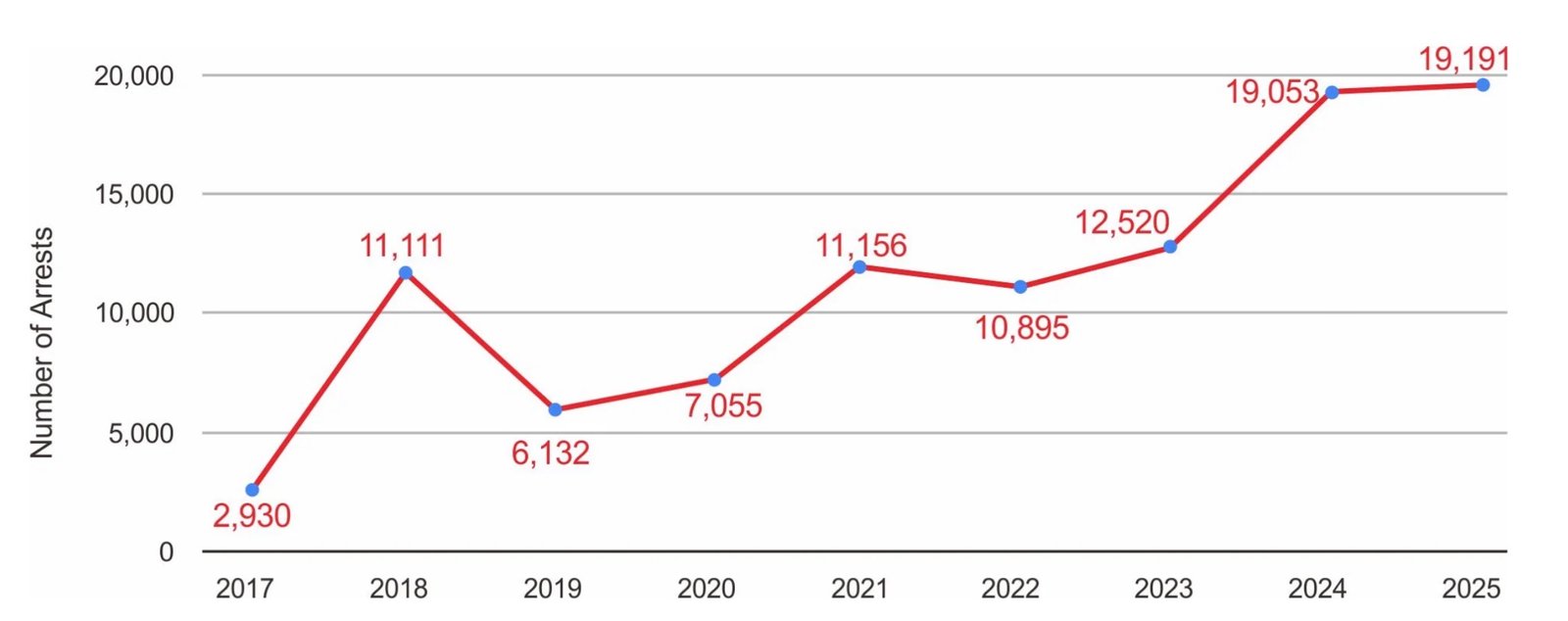

The first thing that stands out is the sheer scale of the situation. The report confirms that at least 19,191 CAG members were detained in 2025. This marks the highest number since the Church published its annual report in 2017. The authors caution that this figure is likely incomplete; entire regions remain shrouded in censorship and surveillance. The most brutal operations, particularly in Xinjiang, often leave no trace. Yet the numbers available reveal a campaign that has shifted from repression to outright eradication.

The authorities continue to use money as bait, increasing the stakes to encourage nationwide reporting with rewards ranging from hundreds to thousands, and even tens of thousands, of U.S. dollars. Police officers who arrest CAG members are rewarded, and those who exceed their quotas are promoted and granted other honors. Under this profit-driven system, elderly believers have become a clear target. The number of people persecuted has reached a new high.

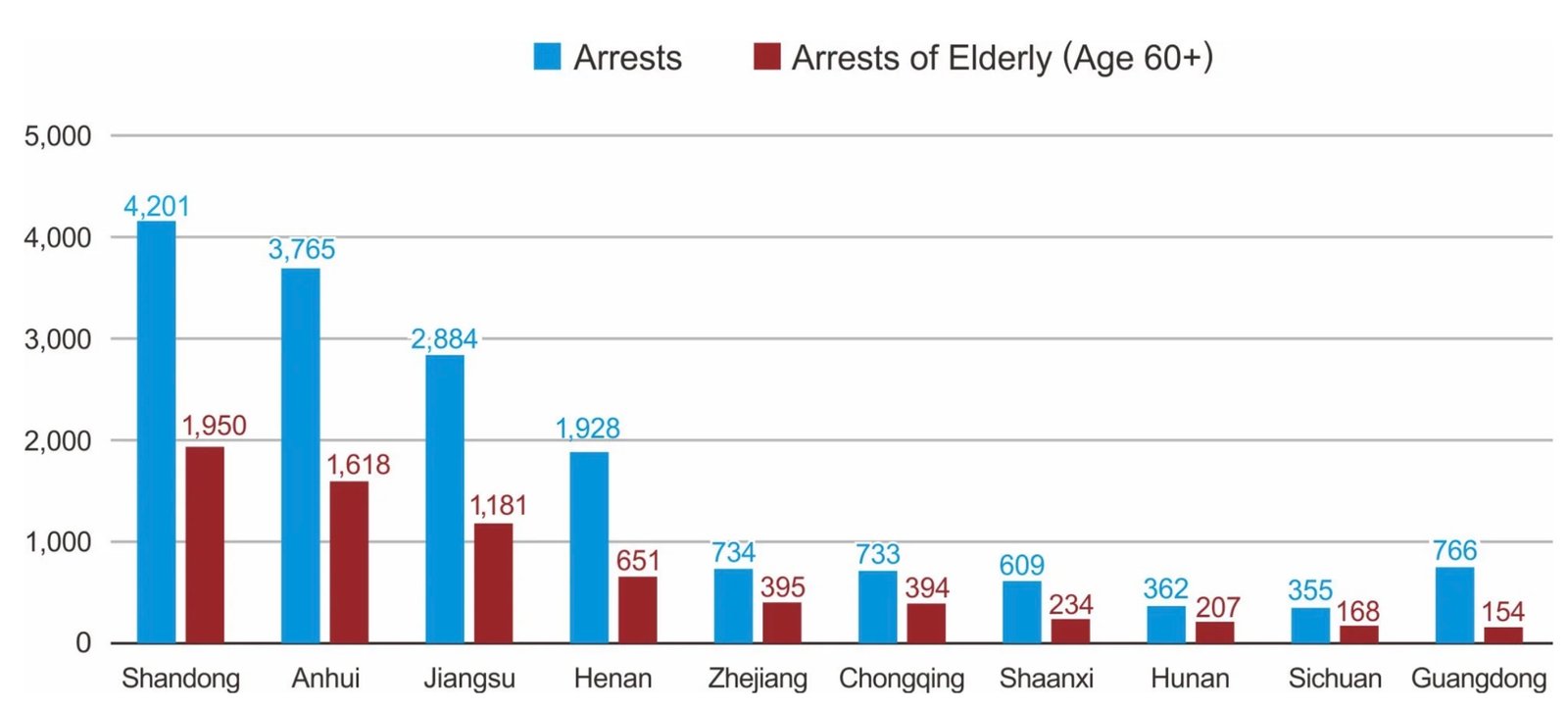

Approximately seven thousand believers over the age of sixty were arrested across just ten provinces. Some were in their eighties and nineties; the oldest known detainee was ninety-three. In any society that values dignity, age should be a protection. In China, it has turned into a vulnerability. The report describes elderly Christians dragged from their homes, interrogated for hours, forced to stand for extended periods, deprived of sleep, and subjected to indoctrination sessions that younger detainees often struggle to cope with. The authorities’ goal is to use every means to force them to renounce their faith and sign the “Three Statements” (Statement of Guarantee, Statement of Repentance, and Statement of Severance). Some of these elderly believers died in custody or shortly after release, unable to endure the combination of physical abuse and psychological pressure.

The report details the cruelty faced by detainees with such precision that there is little room for doubt. Torture is not rare; it is a regular practice. Believers are beaten, deprived of sleep, forced into painful positions, and subjected to violent “transformation” sessions meant to shatter their resolve. Many are coerced into signing statements about renouncing their faith. At least twenty-three CAG members died in 2025 due to persecution. Untreated illnesses, injuries from torture, or the gradual decline of health under constant pressure caused these deaths. The case of Yu Xiaomei, who died after months of medical neglect and declining health following her arrest, highlights a system that treats believers as disposable.

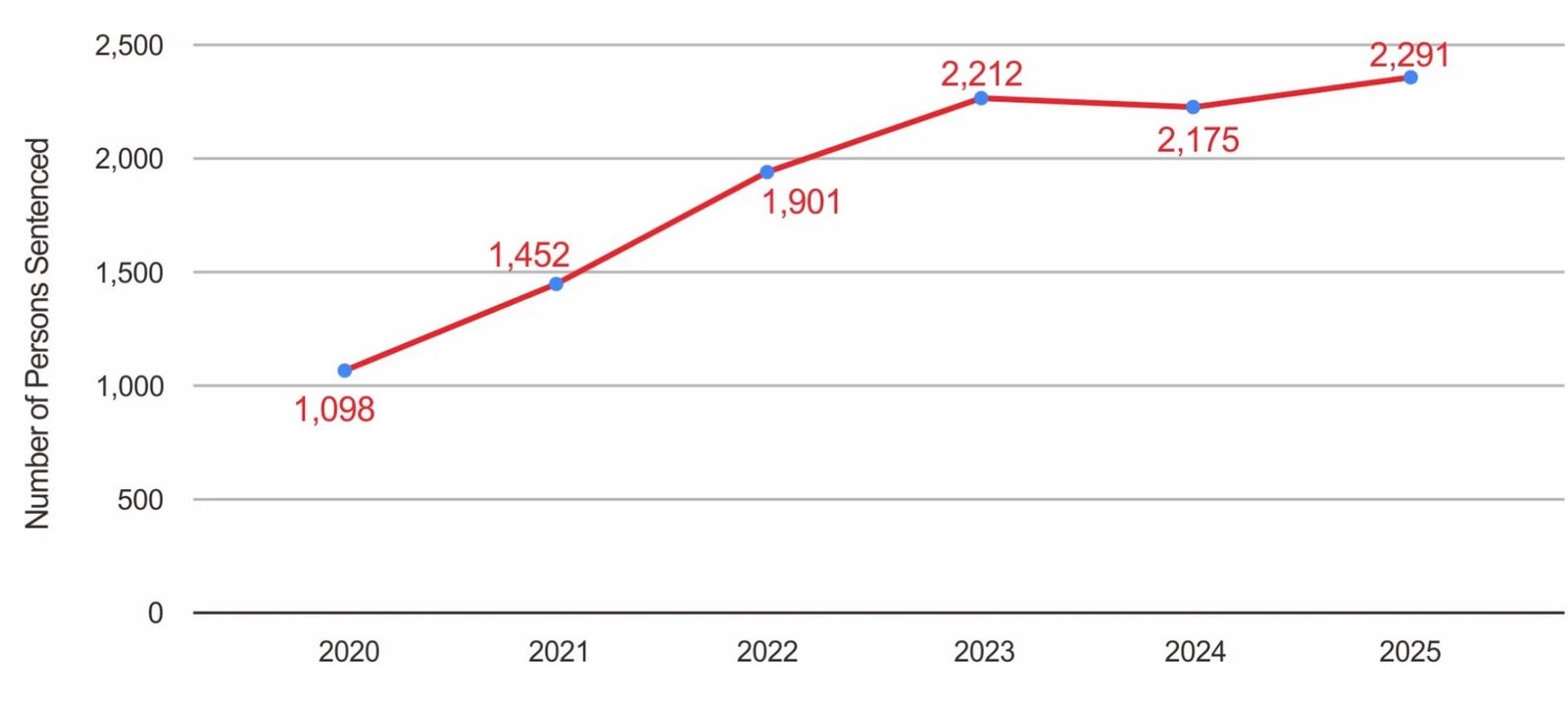

Sentencing has also become more severe. Courts handed out at least 2,291 prison terms in 2025. Nearly a thousand believers received sentences longer than three years, and over a hundred received sentences exceeding seven years. The longest sentence surpassed ten years. The youngest person sentenced was just twenty-one. Fines reached levels that would bankrupt most families, with some believers facing obligations of up to fourteen thousand US dollars. Alongside imprisonment, authorities seized at least 330 million RMB in church and personal assets, crippling the community’s ability to operate and punishing believers even after their release from prison.

Behind these figures lies an increasingly sophisticated machinery of repression. Mass arrest campaigns sweep through provinces like Shandong, where arrests rose by seventy-two percent in a single year. Surveillance technology, including facial recognition, big data systems, drones, and thermal imaging, is deployed with military efficiency. In some places, police used high-grade thermal cameras to track believers in real time. Citizens are encouraged to report on CAG members for cash rewards of up to 14,000 dollars. Police officers receive bonuses for each arrest they make and, more importantly, the authorities have closely linked the arrest of CAG members to the officers’ performance evaluations, creating a twisted incentive structure that turns persecution into a profitable business.

The regional breakdown in the report shows that no area of China is unaffected. Shandong, Anhui, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Henan, Zhejiang, Chongqing, and Shaanxi each contribute their own bleak chapter. Elderly believers in Anhui and Jiangsu were rounded up in unprecedented numbers. In Guangdong, CAG members faced torture and long-term surveillance. The pattern remains consistent: raids, interrogations, forced confessions, and the deliberate dismantling of church networks.

The accounts of those who died are some of the most chilling. They include believers who succumbed to untreated illnesses after being denied medical care, those worked to exhaustion, and others who could not bear the psychological strain. Some deaths happened after release, when the trauma of detention and the constant threat of renewed persecution became unbearable.

Even those who manage to survive imprisonment rarely return to ordinary life. Many face monitoring, harassment, or are forced into ideological “re-education.” Some vanish entirely, living under false identities or constantly on the move to avoid detection. The report makes it clear that the CCP’s goal is not just to punish individuals but to “zero out” the faith — to eliminate The Church of Almighty God from society through fear, surveillance, and attrition.

What is striking is not just the extent of the repression, but the cold efficiency with which it is executed. The CCP has established a system that rewards participation in persecution, weaponizes technology, and uses the legal framework as a means of ideological control.

The 2025 CAG report serves as a stark reminder that religious persecution in China is a pressing issue. It affects tens of thousands of people whose only “crime” is their belief. It also serves as a call to the international community not to look the other way. Extensive empirical evidence shows that the CCP’s campaign against The Church of Almighty God represents the most extensive and brutal religious crackdown in China. According to the report, silence would only strengthen those who carry out these horrible acts.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.