Chinese citizens on the mainland are punished for using foreign websites or social media. Those who post comments unfavorable to the regime may end in jail.

by Xiao Baiming

China has introduced a sophisticated censorship mechanism known as the Great Firewall of China to limit and control its citizens’ access to foreign information sources online and social media platforms. Those who want to bypass it have to use virtual private networks (VPN) or other methods. Many people attempt to do just that but are often discovered and punished by the authorities.

In late 2019, numerous China’s diplomats overseas opened Twitter accounts, in an attempt to remold CCP’s image abroad, which also caused criticism for double standards: Why ordinary people are not allowed to bypass the Great Firewall but officials can?

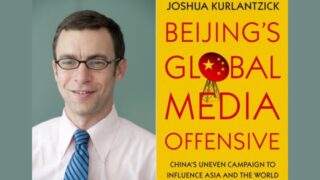

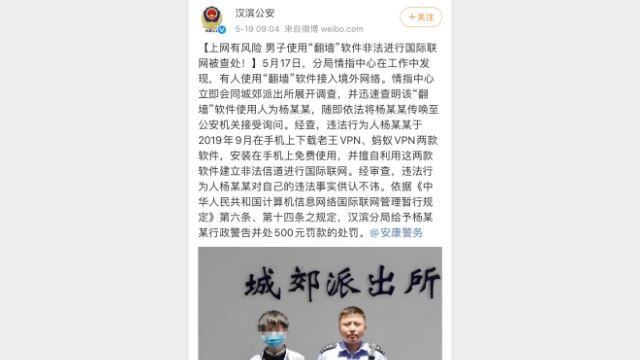

In February, two men from the central province of Henan were arrested for accessing overseas websites. “The police told me that foreign sites report only rumors and forbade me from accessing, reposting, or liking them,” one of them told Bitter Winter. He was fined 500 RMB and released after signing a statement of repentance.

The other man, accused of “disturbing social order,” was instructed by the police “to stay away from the Americans and be loyal to China” because the former “indoctrinate him while the Communist Party has brought him up.”

Some people are put under surveillance as “dangerous” elements after they are caught bypassing the Great Firewall. In late 2019, a college student from the northern province of Shanxi visited Beijing. He was surprised when the police contacted him on the phone to question about his trip. He soon realized that his whereabouts were known to the officers because he had been listed as a key target of surveillance after the National Security Brigade summoned him a year ago for bypassing the Great Firewall.

Those who post comments criticizing the Chinese government on non-Chinese social media face even more severe punishment. A Twitter user “中国文字狱事件盘点(@SpeechFreedomCN),” has collected public records of netizens from mainland China punished for this “offense.”

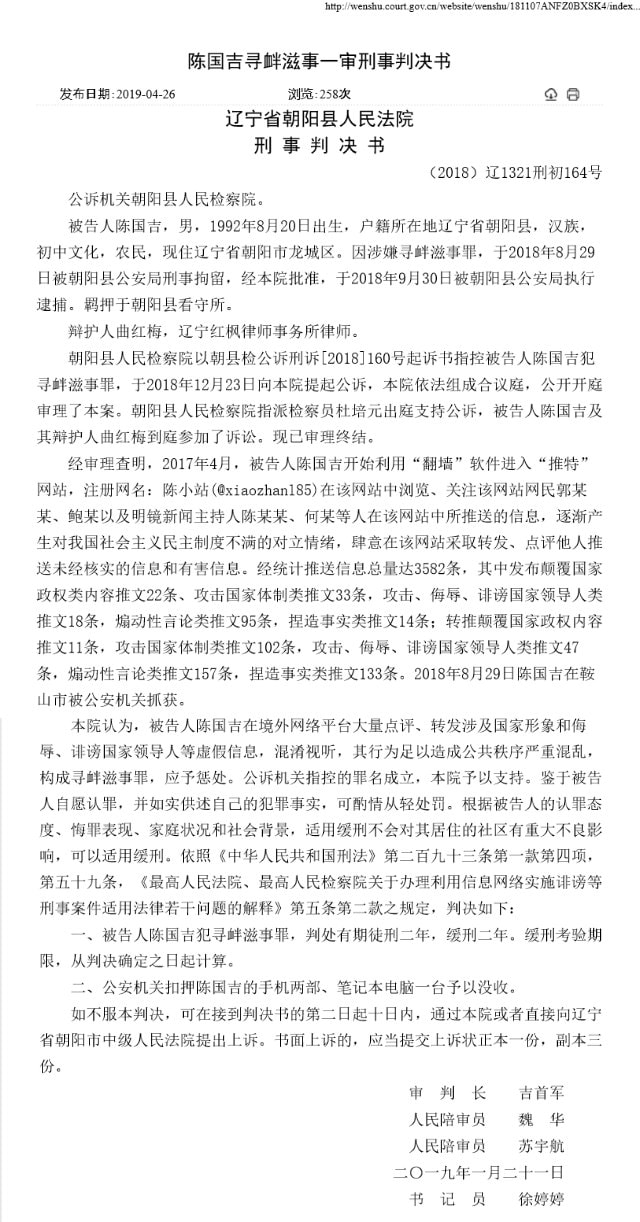

In one such case, the People’s Court of Chaoyang county in the northeastern province of Liaoning gave a suspended two-year sentence in January 2019 to Chen Guoji for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” and “causing grave public disorder.” His crime? “Liking, commenting, and reposting a large number of false messages, involving those that damage the state’s image and insult and defame its leaders on overseas online platforms.” Chen Guoji’s “wrongdoings” are broken down in the verdict: he had posted 22 tweets deemed as “subversion of state power,” 33 tweets as “attacks on the state systems,” 18 tweets as “attacks, insults, and defamation of state leaders,” and 95 tweets “as making inciting speeches.” Even the tweets he had reposted were regarded as a basis of criminal punishment.

In November 2019, the No. 1 People’s Court of Zhongshan city in the southern province of Guangdong sentenced Wang Beiyuan to one year in prison on “defamation” charges. The court determined that among over 2,000 of his tweets, some were considered as “harmful information slandering state leaders, defaming the Chinese government, and attacking national polices, gravely damaging the state’s image and harming the state’s interests.”

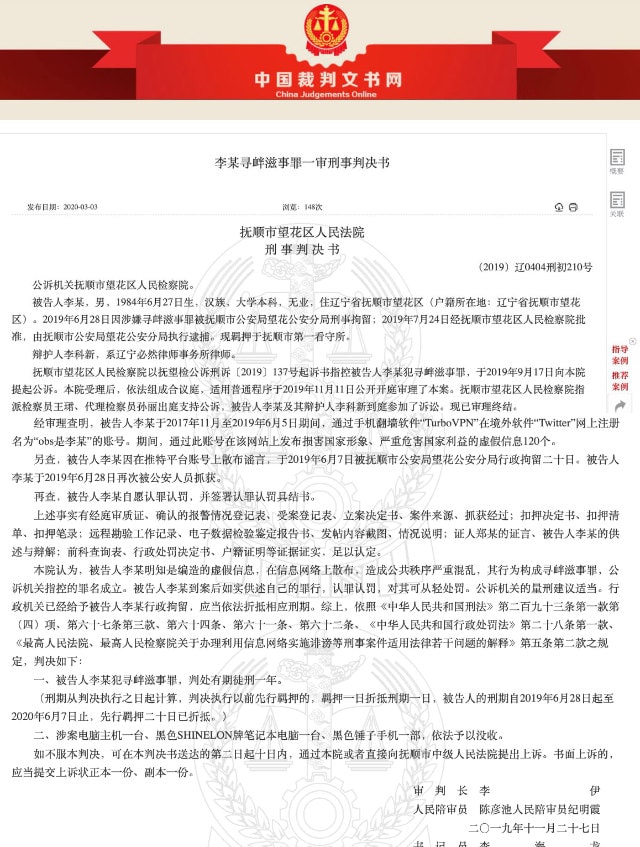

The same month, Mr. Li from Liaoning’s Fushun city was sentenced to one year in prison for bypassing the Great Firewall and posting on Twitter 120 “false messages damaging the state’s image and causing grave harm to the state’s interests.”