Instead of helping people, some mental health institutions in China are used to “reform” dissidents, even people petitioning the government or religious believers.

by Li Mingxuan

Three generations of a family live together in extremely impoverished conditions in a village administered by Zibo city in the eastern province of Shandong. On top of that, the wife of the head of the household is disabled, so he has repeatedly applied to the local government for subsistence allowance but was refused each time. In 2018, the man decided to go to Beijing to petition the central government. Instead of solving his family’s problems, he was arrested by Public Security Bureau officers and taken to a psychiatric hospital.

The man recalled that in the hospital, he was tied to a bed when he refused to take the medication the doctors gave him. After a few such incidents, he gave up and decided to take the pills himself to avoid being tied up. He later learned that his town’s authorities had instructed the hospital to force him to take the drugs. When he was released after a month, his mental condition was visibly affected. Since then, he became a target of the government’s surveillance. In September 2019, the police came to his house again, threatening to give him a hefty sentence if he petitioned again.

Stories like this are not isolated cases in China: dissidents, believers, or petitioners are jailed in psychiatric hospitals for years. For law enforcement officers, it’s an easy way to earn extra cash from the people who want to deal with the “troublemakers” and also a possibility to demonstrate to their superiors that they work “effectively.”

A staff member in a psychiatric hospital in Shandong’s Dezhou city told Bitter Winter that police officers quite often bring people in handcuffs and shackles, their heads covered with black hoods, for “treatment.”

“The hospital treats them regardless if they are ill or not, as long as they are sent here,” the employee explained. “If they refuse to take drugs, we’ll force them. The government does not tolerate petitioners; they call them ‘mentally ill.’ When they are sent here, their mental condition is normal, but it deteriorates after the ‘treatment.’”

He remembered an elderly man who was brought to the hospital three times for petitioning in Beijing. His family had to pay all his medical expenses. The third time, he was only released after his family wrote a statement promising that the man would not petition again.

“Very few people held here are actually ill,” the employee said. “It may look like a hospital, but in reality, it is no different from a prison. The gate is secured with several big iron chains, so there is no way to escape. To keep patients weak, the hospital only gives them little food.”

Along with petitioners and dissidents, people of faith are also often kept in psychiatric hospitals—one of the means of how the government forces them to give up their beliefs.

According to a staff member in a psychiatric hospital in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, when members of The Church of Almighty God (CAG) are brought in, the hospital starts the “treatment” immediately, without any tests or examination. The doctors there claim that they apply “special treatment” for religious believers.

“To force me to take pills, two male doctors pressed me down on a desk, shocked my back, hands, and feet with an electric baton,” a CAG member recalled her painful experience in a psychiatric hospital in 2017. “My entire body was in pain and trembled. I could hardly breathe, and I couldn’t control my bladder. The torture only stopped when I agreed to take the drugs.”

During more than a month in the hospital, the woman received six shock treatments, fainting on two occasions. The doctors threatened that her son’s job would be affected if she continued practicing her faith. After her release, she immediately went into hiding, hoping to evade more arrests, even though she was still frail.

“As a result of electric shocks, my memory declined, and my hands and feet often felt numb. I started feeling a bit better only after six months,” the woman remembered.

A CAG member from Tianmen city in the central province of Hubei spent 157 days in a psychiatric hospital. “A doctor told me that because of my faith, I was a mental patient, and there was no need for further tests,” the woman remembered. Once, three nurses forced her to take the drugs intended for people with mental health conditions, even though they admitted that she had no related symptoms. Such were the hospital’s rules, the nurses told her. They threatened to tie her up if she refused to take the drugs.

“Forced commitment in psychiatric facilities remains a common form of retaliation and punishment by Chinese authorities against activists and government critics,” Chinese Human Rights Defenders, a coalition of Chinese and international NGOs, reported in its briefing in 2016. “The practice endures though it is apparently illegal, according to China’s first Mental Health Law, which was enacted three years ago, on May 1, 2013.”

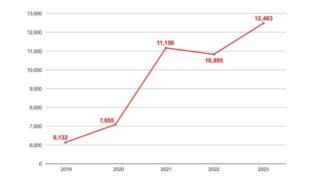

Thousands of people continue to be sent by the government to psychiatric hospitals every year in China as a punishment. In one of the recent cases, Dong Yaoqiong, the “ink girl” who live-streamed a video of herself defacing a Xi Jinping poster, was held in a psychiatric hospital for over a year. She was released on November 19, 2019.