She is now allowed a few days of medical care. She should be freed, unconditionally.

by Massimo Introvigne

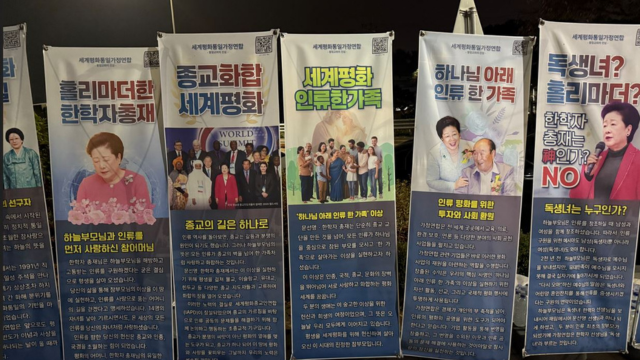

Mother Han, Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon, the leader of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (formerly known as the Unification Church), revered by many as the “Mother of Peace,” has been granted a temporary reprieve from her detention. However, it is not freedom, or even compassion. It is a procedural concession wrapped in barbed wire.

After months of international outcry, vigils, and appeals for humanitarian release—citing her deteriorating eyesight and heart condition—the South Korean judiciary has allowed her a few days of medical care and possible eye surgery. Her movements are restricted to the hospital premises. She may only see medical staff or her attorneys. The facility’s name is redacted, and the air of secrecy remains suffocating.

The court’s order, effective until 16:00 KST on November 7, reads more like a surveillance directive than a gesture of mercy. It warns that she may still be summoned for interrogation. It cautions against fleeing or “destroying evidence.” These are not the words one uses for an 82-year-old woman seeking eye treatment. These are the words of a system that refuses to see.

This is the same system that indicted her under charges many view as politically motivated and religiously repressive—a theme “Bitter Winter” has documented extensively. The same system that ignored her age, her health, and her legacy of peacebuilding. And now, even in illness, it cannot let go of its grip.

This is a woman who has spent her life advocating for reconciliation, interfaith dialogue, and global peace. Her followers call her the Mother of Peace, not out of ritual, but out of reverence. And yet, she is treated not as a dignified elder, but as a flight risk.

The delay in granting even this limited medical access is telling. To move the needle, relentless pressure from human rights advocates, religious leaders, and concerned citizens worldwide was required. And still, the result is a half-measure, a gesture that feels more like damage control than genuine care.

We hope that in these brief days, Mother Han will feel the warmth of sunlight, the breath of fresh air, and the presence of Heaven. But we must not mistake this pause for progress. Her condition demands genuine care, her legacy demands respect, and her detention demands scrutiny.

This is not how a democratic nation should treat its religious leaders. This is not how justice should look.

This moment is a mirror for South Korea, the international community, and all who believe in religious liberty and the sanctity of human dignity. We are not pacified by temporary releases and redacted hospital names. We demand more. We demand freedom for Mother Han.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.