Uyghurs in Xinjiang (Credits: Xinjiang, China – Flickr Commons)

China had long denied that “transformation through education” camps for Muslims exist in Xinjiang. Now it announces that all is well, since a new law made them legal.

Massimo Introvigne

Bitter Winter has been among the first media outlets to report extensively on the “transformation through education” camps, which are believed to host 1,5 million inmates in China, mostly religious dissidents. One million of the inmates are Muslims, mostly Uyghurs and ethnic Kazakhs from Xinjiang. Terminology is confusing, and the confusion was used by Chinese propaganda to its own advantage. Since laojiao (劳动教养 or 劳教), “re-education through labor” camps, were abolished in China in 2013, the regime countered that criticism was based on old information. But in fact the laojiao had been replaced by jiaoyu zhuanhua (教育转化), “transformation through education” camps, which are even worse. They are not schools. They are concentration camps, where victims who resist forced “deprogramming” from their religious faith are tortured, in some cases to death.

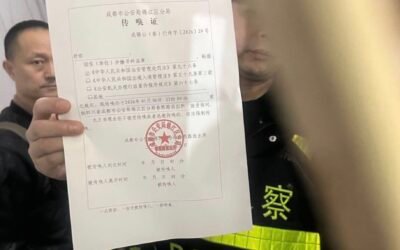

The new camps were also illegal. There was no clear legal basis for them in Chinese legislation. But on October 10, 2018, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced that these problems have been solved, as a new Amended Anti-Extremism Regulation was enacted and published by the 13th Standing Committee of The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’s People’s Congress. The regulation legalizes and standardizes the practice of detaining in “transformation through education” camps “people who have been affected by extremist thoughts,” by which the CCP means religionists who are not prepared to renounce their faith. The regulation, though, only legitimizes camps in Xinjiang, while they exist outside the “autonomous region” as well and host religious and political dissidents other than Muslims.

Another provision of the new regulation, the CCP announced, is that it “deletes previous clauses that detail the level of punishment given to different violations and their seriousness. Previously, if the circumstances were relatively minor, violators would be criticized by the public security department. The amendment now allows authorities to give offenders harsher punishment.”

This means that even more religious “extremists,” a term borrowed from Russia and applied to members of all religions not approved and controlled by CCP, can now be detained in the camps or even given “harsher” punishments.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.