The attempts to put religion under state control in Africa now use “cult” stereotypes imported from France, China, and Japan.

Rosita Šorytė*

*A paper presented at the Second Conference on Religious Freedom in South Africa, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, January 29–30, 2026.

The existence of an anti-cult movement in Africa is a subject of debate. The term “anti-cult” is not indigenous to the continent; instead, it has been introduced through media sensationalism, foreign non-governmental organizations, and governments seeking justification for new regulatory measures. Despite its external origins, anti-cult rhetoric has become entrenched in several African countries, shaping public perceptions of minority religions and influencing state policy. To understand the development and impact of this phenomenon on institutions such as The Revelation Spiritual Home (TRSH), it is necessary to trace the history of anti-cultism in Africa and analyze the driving forces behind its adoption.

Mauritius in 2004 provides a significant case study for understanding how African media may respond to controversies involving so-called “cults.’ In a quiet neighborhood near Port Louis, police discovered ten decomposing bodies in a house belonging to the family of a woman regarded by relatives as a spiritual leader. While the deaths were shocking, the media response was particularly instructive. One of the deceased had previously been a member of Eckankar, a U.S.-based new religious movement, although he had left the group years earlier. No evidence linked Eckankar to the tragedy. Nevertheless, several media outlets quickly characterized the event as a “collective suicide” orchestrated by an “international cult.” This narrative became so pervasive that Mauritian media occasionally still refer to an “Eckankar suicide.”

The origins of this framing can be traced to anti-cult activists in Réunion, a nearby French territory, whom Mauritian journalists later acknowledged relying on. France has maintained a longstanding policy against so-called “sectes,” and French anti-cult organizations have actively exported their ideology to Francophone Africa. In Réunion, Pentecostal pastors, prophets, and founders of indigenous movements have all been labeled as “cult leaders,” a characterization that Mauritian media subsequently adopted. The Eckankar case thus exemplifies how European anti-cult narratives were introduced into African contexts, where they subsequently proliferated.

Anti-cult campaigns in Africa developed along five major lines.

The first factor is the globalization of anti-cultism. African media have increasingly adopted stories from Europe and North America, where sensational accounts of “dangerous cults” are standard in tabloid journalism. French anti-cult organizations established relationships with African officials, offering training, documentation, and ideological frameworks. Recent governmental reports on “cults” in Africa explicitly reference interactions with French public and private anti-cult agencies. This cross-border exchange of ideas has contributed to framing minority religions as inherently suspicious.

The second factor is the appeal of brainwashing theories. Although discredited academically, brainwashing remains a powerful rhetorical tool for portraying some religious leaders—including African Indigenous Spirituality (AIS) practitioners—as manipulative charlatans. For decades, elites dismissed sangomas and other indigenous healers as “witch doctors,” and brainwashing theories offered a pseudo-scientific justification for this prejudice. If people claimed healing or spiritual experiences, it was because they had been “brainwashed.” The logic was weak, but politically convenient.

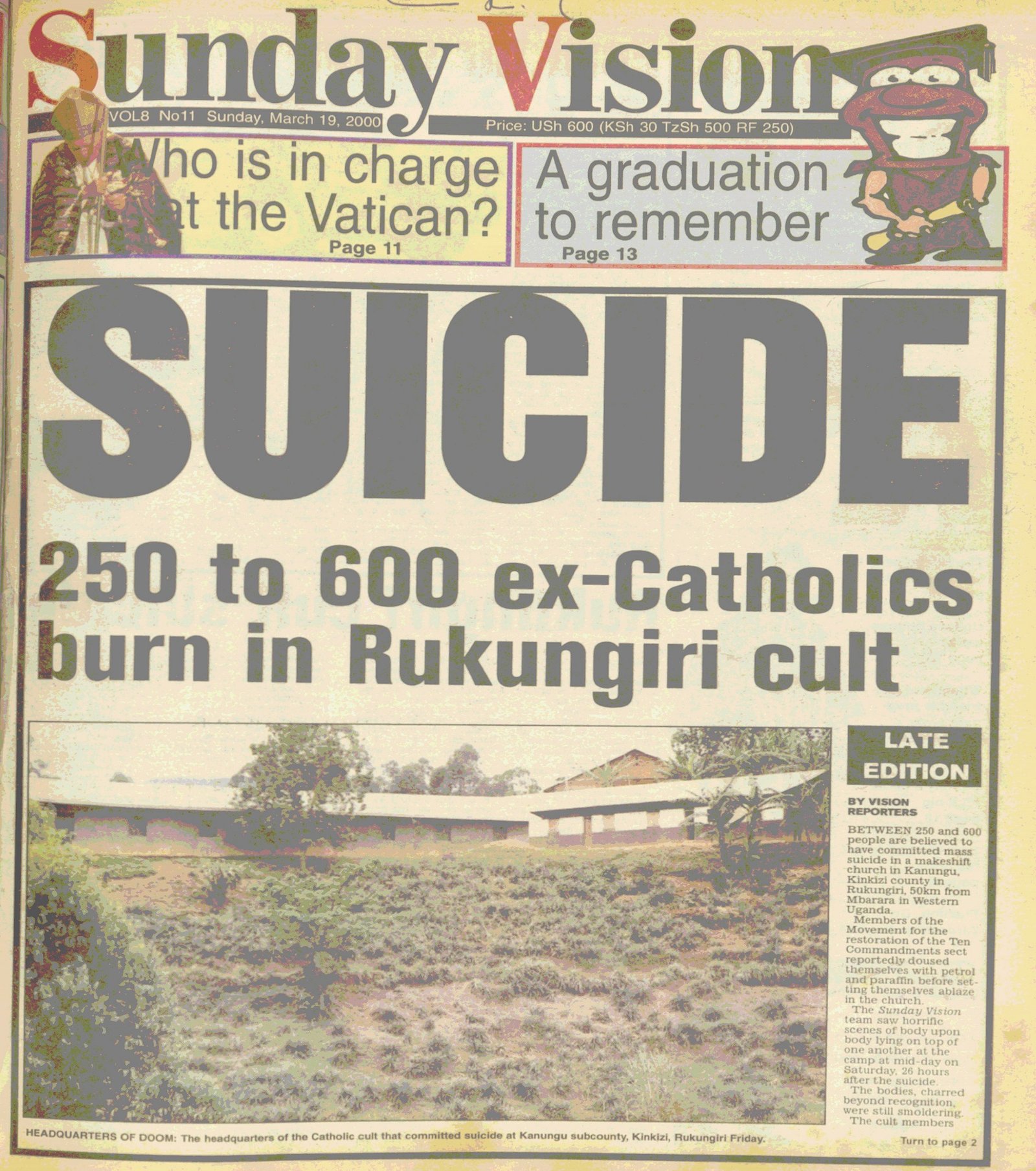

The third factor is the tragedy involving the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God in Uganda in 2000. Although this movement was rooted in fringe Catholic mysticism and bore little resemblance to groups typically labeled as “cults,” the scale of the deaths—possibly exceeding one thousand—generated widespread panic across the continent. While many details remain unclear, the incident has since been cited as a cautionary example whenever a new religious movement appears unconventional or charismatic.

The fourth factor is the Shakahola tragedy in Kenya in 2023, during which followers of Pastor Paul Mackenzie engaged in extreme fasting that resulted in hundreds of deaths. In response, the Kenyan government introduced comprehensive proposals to regulate all religious organizations, referencing collaborations with French anti-cult agencies. Rwanda, Uganda, and Cameroon subsequently implemented their own regulatory measures, with Rwanda, where similar concerns had emerged before the incident in Kenya, closing more than 7,000 independent religious organizations in a single campaign. While the Shakahola incident did not originate anti-cultism in Africa, it reinvigorated such efforts by providing governments with a compelling justification for increased regulatory control.

The fifth factor is the activism of foreign governments seeking to export their anti-cult models. China is the most notable example. Its political influence in Africa is well known. Still, less attention has been paid to its efforts to promote its system of religious management, which requires all faiths to operate under state-controlled umbrella organizations. African politicians and bureaucrats are regularly invited to Chinese training programs that include sessions on “religious stability” and “cult prevention.” Some documents also suggest that, as France did for decades, post-Abe-assassination Japan has used diplomatic channels to promote anti-cultism globally, partly to deflect criticism of its repression of the Unification Church. Anti-cultism has thus become geopolitical.

These five factors created an environment in which African governments and media became increasingly receptive to anti-cult rhetoric. Nowhere is this more evident than in South Africa, where the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities (CRL) has played a central role. Established in 2002 as a Chapter Nine institution under the South African Constitution, the CRL was initially intended to safeguard cultural and religious diversity. However, in 2015, it reinterpreted its mission to include investigating whether certain religious institutions were “harmful,” prompted by sensational media reports of fringe pastors instructing congregants to eat grass or drink petrol.

The CRL launched hearings on the “commercialization of religion and abuse of people’s belief systems,” leading to a 2017 report that bore unmistakable traces of European and American anti-cult ideology. The commission admitted it had relied heavily on media reports rather than scholarly research or direct engagement with the groups being examined. It expressed concern about “false churches” and questioned the legitimacy of spiritual leaders who claimed authority without meeting criteria that the CRL itself never defined. It proposed that all religious organizations be required to disclose finances, elect leaders democratically, and associate with umbrella bodies overseen by the CRL. These umbrellas would be organized by religious tradition—Christianity, African Religion, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Rastafarianism—with the CRL as final authority.

The resemblance to China’s system of “patriotic associations” was striking. The influence of French anti-cult ideology was equally visible. Parliament ultimately rejected the proposals as unconstitutional, but the episode revealed a growing desire to regulate religion in South Africa. The Revelation Spiritual Home (TRSH) became a direct target of this regulatory initiative. Its leader, IMboni Radebe, was summoned to appear before the CRL and to submit TRSH’s financial records. Radebe refused, contending that the CRL’s demands infringed upon constitutional protections of religious freedom. In response, CRL Chairperson Thoko Mkhwanazi-Xaluva characterized him as defiant and attempted to have him arrested for contempt. A TRSH member who sent a spiritual warning to the Chairperson received a three-year prison sentence for allegedly threatening a public official. Although efforts to incriminate Radebe were unsuccessful, the incident illustrates how anti-cult rhetoric can be employed against rapidly expanding indigenous spiritual movements.

The CRL’s ambitions did not end with its failed 2017 proposals. In 2025, it established a Section 22 Committee, ostensibly a mechanism for “self-regulation” of Christian organizations. In practice, the committee functioned as a quasi-judicial body empowered to investigate spiritual abuse, a category unknown to South African law. Although its mandate was defined as “for the Christian sector,” non-Christian institutions also felt threatened, and at a press conference on January 21, 2026, the CRL Commission presented slides explaining that it had decided “to commence with the Christian Sector,” implying that it plans to target, in the future, non-Christian religious and spiritual institutions as well.

The South African Church Defenders (SACD) challenged the committee in the High Court, arguing that the CRL lacked authority to establish such a tribunal. Existing laws already cover fraud, assault, and exploitation; creating a new category of religious infractions usurps the powers of Parliament and the judiciary.

The CRL justified the committee’s actions by invoking the same rhetoric it had used in 2017: the “commercialization of religion,” the need to protect congregants, and the risks posed by unregulated spiritual leaders. But “commercialization” is not a crime; it is a rhetorical tool that allows regulators to depict churches as businesses and pastors as profiteers. Once religion is defined as commerce, it becomes subject to licensing, oversight, and closure. The Section 22 Committee thus positioned itself as the arbiter of legitimacy, determining which churches may exist and which pastors may preach.

Critics observed that the committee exhibited both authoritarian tendencies and bias. Its membership was predominantly male and dominated by representatives from specific denominations. Minority faiths, independent churches, and women were largely excluded. This composition reflected a broader discomfort with religious diversity and a preference for ‘respectable’ institutions, often at the expense of charismatic, unconventional, and indigenous groups.

Recent developments have intensified these concerns. Internal disputes culminated in the resignation of the Section 22 Committee’s chairperson, Professor Musa Xulu, in January 2026. His departure followed accusations of “dictatorship,” complaints about his “passive presence,” and objections to his speaking publicly about the committee’s work. The CRL leadership warned him not to attend a media briefing, and a vote of no confidence followed on January 14. Xulu had already sent a letter of resignation on January 12, stating that he had been appointed to conduct research and facilitate self-regulation, not to develop legislation or place churches under state control. He also revealed that he had been discouraged from consulting the very Christian communities the committee was supposed to engage—an approach he found unreasonable and contrary to the idea of self-regulation. The Xulu incident illustrates the CRL Commission’s determination to proceed with its regulatory project, dismissing any objections, including those from scholars it had itself appointed.

These developments show a broader trend: the globalization of anti-cultism is transforming the religious landscape of Southern Africa. Imported ideologies, foreign training initiatives, and transnational networks are shaping how African governments perceive and regulate minority religions. Institutions such as TRSH, which articulate a confident and expansive vision of African Indigenous Spirituality, become particularly vulnerable to suspicion. Their size, visibility, and distinctive doctrines render them susceptible to accusations of being “cults” even when there is no evidence of harm. The same happens to Christian churches.

Should anti-cult ideology become entrenched within African regulatory frameworks, it is likely to undermine the broader ecosystem of religious diversity. Independent churches, indigenous spiritual movements, and minority faiths would face increased scrutiny, bureaucratic barriers, and the risk of closure. The distinction between safeguarding citizens and controlling belief would become increasingly ambiguous, thereby weakening the constitutional guarantee of religious freedom.

A central challenge lies in differentiating between legitimate concerns regarding abuse and the authoritarian inclination to regulate religion. While some groups within the religious landscape have engaged in harmful practices, employing these cases to justify broad regulations on all religious and spiritual organizations constitutes an overreach. Such measures are frequently driven by foreign ideologies that may not correspond with African contexts.

The history of anti-cult campaigns in Africa serves as a cautionary example. It demonstrates how tragedies may be exploited, how foreign regulatory models may be adopted without critical assessment, and how bureaucratic institutions may be diverted from their constitutional mandates.

The globalization of anti-cultism is not a neutral process. It introduces assumptions about religion, power, and legitimacy that may conflict with both democratic principles and African values. Safeguarding religious freedom in Africa necessitates resisting the adoption of foreign regulatory models and reaffirming the principle that belief should not be licensed, standardized, or subjected to bureaucratic oversight.

The Revelation Spiritual Home, with its focus on African Indigenous Spirituality, its rejection of colonial religious categories, and its growing influence, stands at the heart of this debate. Its experience shows both the potential of religious pluralism and the dangers of anti-cult ideology. Constitutional commitments to freedom of religion should not be weakened by imported fears or domestic overreach. As elsewhere, the price of liberty is constant vigilance.

Rosita Šorytė was born on September 2, 1965 in Lithuania. In 1988, she graduated from the University of Vilnius in French Language and Literature. In 1994, she got her diploma in international relations from the Institut International d’Administration Publique in Paris.

In 1992, Rosita Šorytė joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania. She has been posted to the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to UNESCO (Paris, 1994-1996), to the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, 1996-1998), and was Minister Counselor at the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to the United Nations in 2014-2017, where she had already worked in 2003-2006. In 2011, she worked as the representative of the Lithuanian Chairmanship of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) at the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw). In 2013, she chaired the European Union Working Group on Humanitarian Aid on behalf of the Lithuanian pro tempore presidency of the European Union. As a diplomat, she specialized in disarmament, humanitarian aid and peacekeeping issues, with a special interest in the Middle East and religious persecution and discrimination in the area. She also served in elections observation missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Belarus, Burundi, and Senegal.

Her personal interests, outside of international relations and humanitarian aid, include spirituality, world religions, and art. She takes a special interest in refugees escaping their countries due to religious persecution and is co-founder and President of ORLIR, the International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees. She is the author, inter alia, of “Religious Persecution, Refugees, and Right of Asylum,” The Journal of CESNUR, 2(1), 2018, 78–99.

Languages (fluent): Lithuanian, English, French, Russian.