Australian universities’ warning students about “cults” may end up making them more dangerous for anyone who identifies with a religion.

by Geraldine Smith

In April 2025, the state government of Victoria, Australia, announced that it was initiating an Inquiry into the Recruitment Methods and Impacts of Cults and Organized Fringe Groups. In a press release, the Legislative Assembly Legal and Social Issues Committee, which is managing the inquiry, stated that its purpose is to investigate “harmful tactics used by some cults and other groups to control their members,” and “the methods used to recruit people and the impacts of coercive behaviors.” The Victorian Inquiry is now conducting public hearings, and in its investigation of “coercion” by “cults” and other “fringe groups,” it has turned its attention to the university sector.

One of the explicit targets of the inquiry appear to be new religions, which the Committee refers to as “cults.” The term is being used by the Inquiry despite academics in the study of religion warning that it is a pejorative, harmful, and theoretically useless category. The Inquiry’s problematic use of the term “cults” is a symptom of a broader lack of engagement with both Australian and international academics who have been producing research on new religions for decades—both by the Committee and ironically, the university sector, which houses the very people who hold specialized knowledge on this topic.

In June 2025, the Tasmanian University Student Association (TUSA) published a social media post warning for students to be aware of “predatory cult organizations” operating on the University of Tasmania’s (UTAS) campuses. TUSA’s President Jack Oates Pryor also appeared on the Australian national broadcaster, ABC Radio Hobart, to explain that “cults are active on the UTAS campuses, and we are aware that there are predatory behaviors and that they are using deceptive psychological tactics to target individuals.” TUSA had posted the warning because they wanted to raise awareness of “cult behaviors and tactics” that could potentially harm students through “persuasion and control often for financial gain.” They wanted to provide students with information about the support available to them if they believed that a member of these predatory organizations had approached them or if they had joined one. Pryor said that TUSA had received student complaints about a specific organization but would not identify who the reports were about.

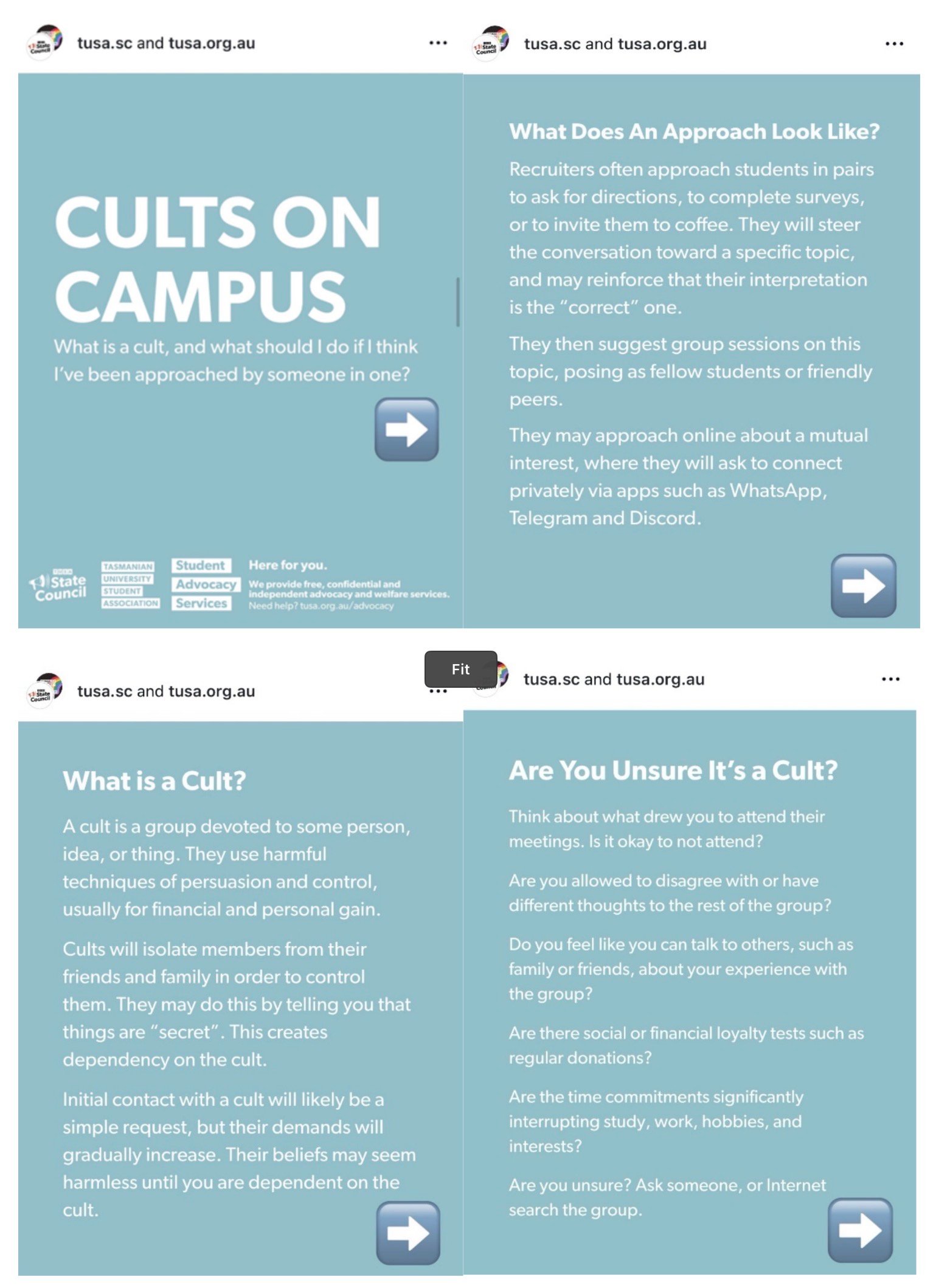

The social media post provides information for students including, as Pryor noted, “a number of ways that students can identify whether they have been approached by a cult.” The post provides a definition of a “cult” and a checklist of tell-tale behaviors that a student can look out for if someone approaches them on campus. According to the post, “Cults on Campus: What is a cult, and what should I do if I think I’ve been approached by someone in one?”, a pair of “recruiters” will approach the student “to ask directions, to complete surveys, or to invite them to coffee.” It says that they will “steer the conversation toward a specific topic and may reinforce that their interpretation is the ‘correct’ one.” The recruiters will then invite the student to a group session “on this topic,” “posing as fellow students or friendly peers.” They may also approach a student online to talk about a “mutual interest.”

The post also includes a list of questions that interrogate whether they are in a “cult,” presumably once they have already begun participating in a community. It asks whether one feels pressure to attend meetings, if they feel they can disagree with the group, if they can speak about experiences in the group to friends and family, if there are financial commitments, and if there are time commitments that significantly interrupt study, work, hobbies or interests. The post also warns that the people who are being targeted by these groups are “international students, first-year students, and students who appear isolated homesick, or to be struggling with university.” The post prescribes that if the student thinks that this applies to them, that they can meet with a TUSA Student Advocate, or contact Cult Information and Family Support (CIFS) Australia, which is a not-for-profit organization that offers counselling and consultation on matters related to “cults.”

The key question is, however, based on the information provided by TUSA’s post, would a student be able to distinguish between someone approaching them from a “predatory cult organization” and someone approaching them from a mainstream religious organization?

The problem with these guidelines is that it could describe how any religious, spiritual, or secular organization, which is soliciting donations, advertising events, or raising awareness on an issue, may approach someone. For a student, in particular, this could be indistinguishable from a so-called “predatory cult organization.” It also appears to have been written with a specific group’s evangelizing practices in mind. They hit a particular Protestant Christian timbre when they mention that the group may insist that they have a “correct” interpretation. Furthermore, religious communities that require significant investments of time, energy, and finances, adhere to a social hierarchy, and teach an all-encompassing belief system—as most religious traditions do—may be superficially interpreted as promoting “cult behaviors and tactics.”

TUSA is clearly motivated by goals of preventing harm and providing information and support, and they are not alone in addressing the topic publicly, nor are they the first. Warnings about “cults” appear on University of Melbourne’s Graduate Student Association web page also entitled “Cults on Campus”, and in MOJO news, which is an independent publication ran by Monash University students, in the article “Cults on campus: The red flags to watch out for.” What these examples seem to suggest is that those who work in Australian universities, especially those who work directly with the student body, are unsure how to respond to complaints about certain religious groups from students. Furthermore, in the absence of guidance they may offer information that is not informed by the most up to date scholarship in this field.

As of yet, no scholars from Australian universities who specialize in new religions, religious studies, or sociology of religion, have been invited as a witness to attend the public hearings for the Inquiry. Rather, representatives in professional and/or leadership roles, and not academics, have been called to provide the panel and the public with vital information about how new religions impact Australian university students.

On the 10th of November 2025, Dene Cicci, Executive Director, Students Group from RMIT University, and Professor Julie Cogin, Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor of Australian Catholic University (ACU) appeared in a public hearing for the Inquiry to discuss their concerns about the presence of new religions on university campuses.

The testimonies provided by Cicci and Cogin however did not center upon problematizing the term “cult,” nor did they take it as an opportunity to highlight the research produced by the sector they represented. Instead, the discussion that ensued before the panel centered upon a single religious community. No other religious or spiritual organizations were discussed during the hearing, despite the potential widespread legislative consequences that this inquiry could have on religious, spiritual, and even non-religious organizations.

The group they spoke about in the public hearing was Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony (SCJ), broadly known as the Shincheonji, which is a Christian organization based in South Korea founded and led by Lee Man Hee. Shincheonji put a great deal of energy into proselytization and have appeared in the Australian media particularly for their evangelical presence on university campuses, particularly in Melbourne. A common accusation both overseas and in Australia is that Shincheonji’s evangelical practices are somewhat covert, in that members do not immediately identify themselves as Shincheonji, and new members may be invited to Bible study sessions without the name Shincheonji being mentioned. The justification given by Shincheonji for their approach to evangelism is because the organization has suffered public harassment and media campaigns condemning the group in both South Korea and abroad, and that potential new members would be immediately repelled by hearing the name. In recent times, however, it has been noted, including by opponents, that Shincheonji is gradually switching from “covert” to “open” evangelism and increasingly uses its name when approaching potential converts.

The representatives for RMIT and ACU were concerned about members of Shincheonji proselytizing to students on campus. They cited the need to maintain student “safety and wellbeing” as the nature of their concerns. However, there was a lack of substantive evidence produced before the panel which demonstrated that Shincheonji’s evangelizing activities posed a threat to student’s “safety and wellbeing.”

Cicci from RMIT shared data on the number of complaints RMIT had received regarding Shincheonji in 2023, 2024 and 2025. The complaints amounted to no more than one to two a year. Cicci noted that RMIT were concerned about the potential security risks for RMIT campuses which are publicly accessible and, particularly for their Melbourne city campus, is in an area where they receive high levels of foot traffic. He spoke at length about concerns about controlling these areas for potential safety risks but did not claim that any security breaches or incidents had occurred on an RMIT campus that was related to a member of the Shincheonji.

Professor Cogin from ACU cited hearing anecdotal evidence from students and parents of students. She said that the impact of Shincheonji could not be represented in data, but they knew that there was a problem through informal reports. She said that by asking students to raise their hands if they had interacted with someone from Shincheonji, they would get around fifty people raising their hands. It was unclear if this was hypothetical, or if she was stating that ACU staff had done this. She also said that Shincheonji’s flyers had appeared on ACU campuses, and that ACU staff had been removing them to protect the students. Yet, upon being asked by a member of the panel if ACU staff had contacted Shincheonji to request them to cease leaving flyers on university property, she said she was not aware. In fact, neither representative said that they had personally contacted Shincheonji to raise these concerns and were unaware if staff in their institutions had contacted Shincheonji.

There was a lack of clarity regarding the credibility of the evidence that RMIT and ACU possessed which directly demonstrated that members of Shincheonji were harming students, yet they insisted that Shincheonji’s activities on university campuses were a significant problem requiring state intervention. Professor Cogin stated that universities needed guidance on how to report their concerns to the authorities and how best to respond to evangelical activities by groups that university administrators perceive as dangerous. Furthermore, ACU students were not prepared to deal with encounters with a new religion that may approach them for proselytizing purposes. Both ACU and RMIT representatives at the hearing seemed to suggest that university students needed to be equipped with more education regarding new religions—and to this last point, the author agrees.

If universities are committed to promoting respect towards religious and spiritual diversity, they should do so without exception. RMIT is committed to an Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Access Framework which affirms RMIT’s commitment to “ensure inclusive and equitable experiences and outcomes” for “cultural, linguistic and religious diversity.” ACU, as a Catholic institution, is also obliged to affirm the values articulated in the declaration from the Second Vatican Council “Nostra Aetate,” which affirms the value of interreligious dialogue, and respect for the dignity of other religious traditions.

To be clear, Shincheonji is a religion, its members are religious in the same way that Catholics, Muslims, or Jews are religious. It is not a “cult” or “pseudo-religion,” and its members deserve the same respect afforded to every other religion. Rather than responding to Shincheonji, or any other new religion, with fear and uncertainty, a better response by the universities may be to focus on educating students on all religious and spiritual worldviews and drawing upon the knowledge held by scholars in this field who reside in their very institutions.

Some religious and spiritual organizations can and have caused catastrophic harm, yet a more constructive response would be to educate students on how to identify harmful behaviors in any religious and spiritual context, without targeting specific groups lumbered with the nebulous category of “cult.” This may involve providing opportunities in degree programs to critically engage with religion and spirituality, and the important intersections this has with race, gender, class, politics, philosophy, and history, supporting religious and spiritual clubs and societies, and encouraging interfaith initiatives. Religious literacy ought to be a priority for any university interested in promoting safety for religiously and spiritually diverse students, but actions and rhetoric based upon fear about new religions will run directly counter to this.

If misinformation about new religions prevails, it threatens to legitimize religious discrimination on Australian university campuses under the aegis of protecting student “safety and wellbeing.” Anyone who is associated with a religious or spiritual identity, to a fellow student, may appear predatory, deceptive, and harmful, especially to those who have low levels of religious literacy and have been warned of predatory “cults” in their midst. The more these public discussions take place without those leading the discussion being informed by rigorous scholarship in this area, the more that misinformation and prejudice will shape the Australian public’s understandings of religious and spiritual diversity. A better path would be to draw upon the resources that educators, scholars, and researchers in this field provide, and utilizing their specialized skillset, knowledge, and methodologies to make informed choices about how to respond to the challenges that new religions may present.

Geraldine Smith is an interdisciplinary scholar in the fields of studies in religion, sociology of religion, and performance studies. She works as an associate lecturer and researcher at the University of Tasmania and the University of Sydney. Her doctoral research was on the role of multifaith events in facilitating respectful relations between religiously diverse communities and was part of the Australian Research Council Discovery Project “Religious Diversity in Australia: Strategies to Maintain Social Cohesion.” She has published on the multifaith movement, digital activism, religious belonging amongst young people, and new religions. She is currently a co-author on a forthcoming book on the history of new religions in Australia.