Religious liberty is not only the freedom of believing or non-believing, but that of living one’s life according to one’s belief or non-belief. Yet, Japan curtails it. The case of the Family Federation.

by Marco Respinti*

Article 1 of 4.

*Under the title “The Crisis of Religious Freedom and Democracy in Japan,” this paper was presented in different versions at conferences organized and hosted in December 2024 by the International Coalition for Religious Freedom (ICRF) Japan Committee and constituting a lecture tour in Japan that brought the author to speak at Bunka Koryu Kaika, in Hiroshima, on the 6th, at Tokyo City Vision Center in Tokyo Kyobashi on the 8th, at Niterra Civic Hall in Nagoya, on the 9th, and at ACROS Fukuoka, in Fukuoka, on the 10th.

It is with sincere gratitude that I accepted the flattering invitation from the Japan Committee of the International Coalition for Religious Freedom (ICRF) to visit again your beautiful country. On July 22, 2024, I had the honor of delivering a few remarks before the General Assembly of the Japanese Committee of ICRF, which gathered on the theme “Religious Freedom and Future of Democracy.” And I had also earlier opportunities to visit beautiful Japan. Now the ICRF has requested me to conduct a lecture tour that is bringing your servant in four different venues of four Japanese cities, again under the general title “The Crisis of Religious Freedom and Democracy in Japan.” It is a clear sign that the problem is still there. For me, it is a wonderful opportunity to learn more about Japan and religious liberty from colleagues, friends, lawyers, specialists, activists, and other speakers who are addressing the same topic during these days.

Let me immediately express my deep sympathy and admiration for Japan, its history, and its culture. I also admire Japan as a vibrant democracy. It is a country that has suffered much, including unprecedented and unique horrors from which other nations have been, thanks to God, spared.

I am a foreign citizen and cannot speak your language. I am a guest and of course I have no title to judge Japan—nor is it my intention to do it. But one thing I know for sure, and this is universal. A pivotal element of a healthy society and a distinctive character of a true democracy is freedom of religion, belief, or creed for everyone. International treaties call it “FoRB”: freedom of religion “or belief.” This is actually important. Practices that are not technically “religion” are still manifestations of “belief” and are thus protected by FoRB. I want to push this statement even farther: FoRB for everyone is the first “political” human right, immediately following the right to life of all human beings.

Human beings are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights. Life is the first, because, without it, there are no human beings. The second is the right to freely address the most important question of life. It is the question regarding the existence, or non-existence, of God, a Supreme Being, an Ordinating Principle, an Ultimate Cosmic Force, or whatever name you may give to it. If and when human beings are free to address that decisive and final question, they are indeed truly and ultimately free.

Religious liberty is not only the freedom of believing or non-believing, but that of living one’s life according to one’s belief or non-belief. Belief and non-belief directly concern the organization of life, not only in the private sphere (where no one can really curtail that right), but in the public sphere as well. This is why I define FoRB for everyone not only as the fundamental right of human beings, but also as their first political right. It deals in fact with the “polis,” πόλις, the ancient Greek term meaning the “public sphere,” from which the world “politics” derives.

Furthermore, from FoRB come all other human rights. In fact, if and when human beings are left free to address that ultimate, decisive, intimate as well as public question, they can live their life accordingly and enjoy all its implications in terms of liberties and rights. Freedom of expression, association, and education are important, intimate, and public rights but in an ideal list or hierarchy they come after FoRB, and it can even be argued that they derive from it.

FoRB should then concern every human being, every protagonist of a healthy society, and every true builder of democracy. Directly or indirectly, FoRB is always at stake everywhere. It has been so throughout human history, directly or indirectly. Societies and empires, nations and political communities have been built or destroyed, came and went in time, because of the direct or indirect implications that FoRB has with the organization of the public lives of people and with all other human rights.

Let me repeat it clearly. FoRB should always concern every human being—not at the individual level only, but for society as a whole and for all humanity. If and when even one single human being does not fully enjoy FoRB, then all human beings suffer the consequences of this loss. This demonstrates that the question of religious liberty is the most serious question of them all.

Scholars have identified FoRB as the most threatened human right in the world today.

FoRB is threatened and persecuted in too many different countries, where social cohesion, peace, and harmony are undermined by hatred, ideology, and lust for power. We call those countries non-democratic regimes. We understand democracy, whatever institutional form a country’s political community may have, not as yet another regime, but as the good exercise of power by authorities who aim at the common good and the participation of the people to the life of the “polis.”

Unfortunately, though, even democratic countries may and do suffer the diminishment of the right of their citizens to FoRB. Persecutions may manifest themselves differently: for example, at the fiscal, administrative, organizational, and cultural levels. Those democracies that curtail or deny FoRB are then incomplete democracies. They need substantial reform.

We understand that also in Japan FoRB is today diminished or threatened.

“Bitter Winter,” the online daily magazine specialized in religious liberty that I have the honor to serve as Director-in-Charge, a capacity that brings me in this country as a concerned observer to learn and discuss the topic, has covered the difficulties of FoRB in Japan in the last few years. They greatly increased after the assassination of Abe Shinzō (安倍 晋三, 1954–2022)—in Asian names, the family name comes first—in the city of Kashihara, Nara Prefecture, Japan, on July 8, 2022.

Former Prime Minister of Japan, from 2006 to 2007 and from 2012 to 2020, Abe was shot dead by Yamagami Tetsuya (山上 徹也), 41, a former member of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. Following that tragic event, a controversy started over the Unification Church, now called the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, addressed to simply as “Family Federation” (FF) from now on in this speech.

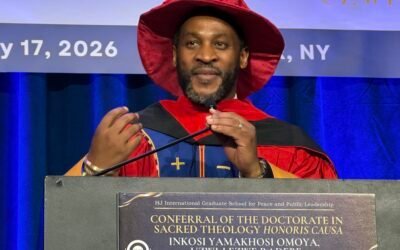

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.