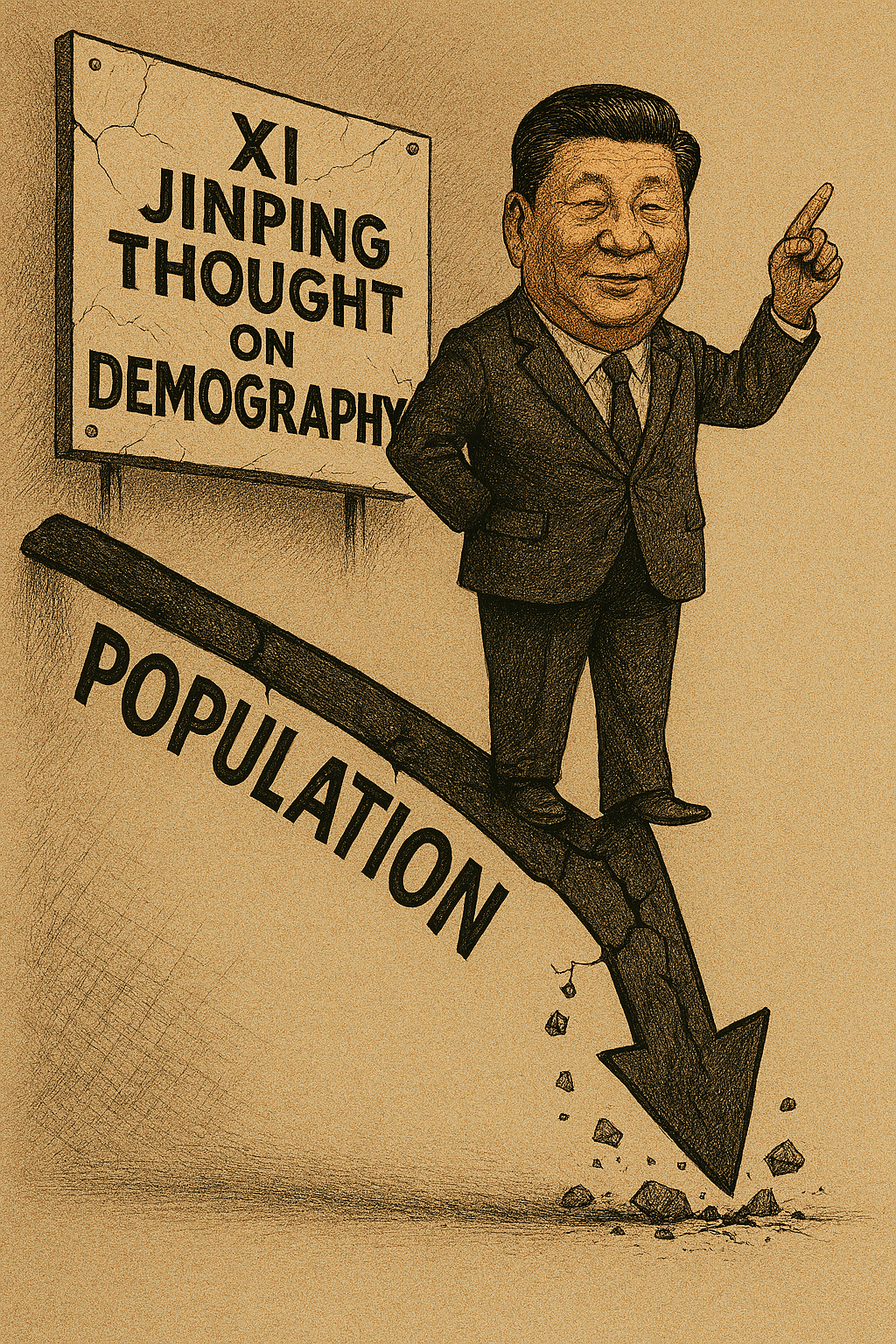

China’s new official doctrine admits the birthrate won’t recover—and rebrands decline as “high-quality development.”

by Massimo Introvigne

In the ever-expanding galaxy of Xi Jinping Thought, which already includes perspectives on ecology, diplomacy, socialism, cybersecurity, literature, and even toilets, it was only a matter of time before demography received its own focus. Now, thanks to an article published on January 20 in the official CCP newspaper “People’s Daily,” we have it: Xi Jinping Thought on Demography. It is indeed a milestone and something really new, but not because it offers solutions to China’s population crisis; instead, it acknowledges that this crisis cannot be solved.

This article does not showcase the typical triumphant writing of the Party’s leading newspaper. Instead, the tone resembles a resignation letter full of policy language. The authors, He Dan, Director of the China Population and Development Research Center, and Wang Qinchi, a Special Researcher at the Beijing Research Center for Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, do not pretend that the birth rate is recovering or that the aging trend is improving. They present something different: a shift from trying to reverse the decline to simply adapting to it. The aim has changed from fixing demographic issues to enduring them.

The article starts with a precise diagnosis: China is facing “fundamental demographic trends that are difficult to reverse.” This includes not only a shrinking labor force and declining birth rates, but also a mismatch between population growth and economic needs, as well as a persistent shortage of services for older people and children. The authors use the term “tight equilibrium” to describe the balance between population and environmental capacity, particularly in poorer or more fragile areas; this term sounds like it comes from a climate change report.

Next comes a rhetorical shift. Instead of suggesting new incentives for childbirth or migration, the authors redefine the problem as a move toward “high-quality population development.” This isn’t a solution; it’s a rebranding effort. Xi Jinping advises “recognizing, adapting to, and leading the new normal of population development.” Essentially, the decline is here to stay, and we may as well present it as a policy victory.

To replace the previous idea of demographic abundance, the article introduces the notion of a “comprehensive demographic dividend.” This focus is no longer about quantity; it centers on quality—education, health, and productivity. The aim is to extract more economic value from a smaller population. The phrase “maximize benefits while minimizing harm” appears, which is typically used in disaster management rather than in national planning.

However, this new approach faces many challenges. The authors acknowledge that institutional and systemic barriers still exist. Social security is insufficient, childcare is inconsistent, and health initiatives are lacking. Reform is labeled a “complex systemic project,” which translates to “we are unsure how to manage this.” Cultural views toward marriage and childbearing are also problematic, though the article and the celebrated Xi Jinping Thought on Demography lightly avoid addressing the central issue: the one-child policy.

That longstanding policy, enforced with harsh consequences, fostered an anti-natalist mindset that Party slogans cannot easily change. The Party has never openly acknowledged that the policy was wrong—only that it was “adjusted”—meaning there is no moral reset, no cultural accountability, and no space for genuine persuasion. You cannot ask people to have more children while refusing to admit that you previously unjustly punished them for doing just that.

Thus, Xi Jinping Thought on Demography invites the nation to live with these consequences. It represents a form of ideological hospice care: handling decline with dignity, reframing failure as wisdom, and hoping that quality will make up for quantity. It is also, in a sense, a confession. The Party that once prided itself on controlling the reproductive future of 1.4 billion people now concedes that the future may not cooperate.

There is something almost touching in this transformation. For decades, China’s population was seen as a tool to manipulate, a graph to adjust, a resource to maximize. Now, it is a challenge to be faced. Xi Jinping Thought on Demography does not promise a revival. It promises resilience. In the language of Chinese officialdom, that is as close to surrender as one is likely to see.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.