The country’s sufferings earned Bangladeshis the respect of the world. But its constitutional architecture is a patchwork at risk of explosion.

by Marco Respinti

Article 3 of 4. Read article 1 and article 2.

When I visited Bangladesh in May 2023, I crossed my paths with different observers. Among them, there were several representatives and leaders from NGOs and the Bangladeshi civil society. In all cases, they came from different walks of life and social classes. They also had different religious persuasions, including Sunni Muslims, Ahmadi Muslims, Christians, Jews, Hindus, and Buddhists. In a few cases, they also represented interfaith civic organizations. The most recurrent word in all their speeches and talks, both formal and informal, was “secular.”

Their attitude toward the word, and their use of it, divided them into two groups—those who praised Bangladesh for being a secular country, and those fearing that Bangladesh could stop being secular. In both cases, they all advocated “secularism” for the country, even hoping to strengthen it.

Now, one could expect advocacy for secularism from agnostics and non-believers, finding it natural (which is not the same as sharing their opinion) that they regard religions as the root cause of intolerance and violence, and blame faiths and churches for conflicts. Much more puzzling is to witness such an open advocacy coming from believers. Very few people I met in Bangladesh, be they Bangladeshis (the majority) or non-Bangladeshis, were non-religious or non-believers. It was then that I learned that in Bangladeshi “secularism” there is more than meets the eye.

The Bangladeshi case seems a perfect exemplification of the problems connected with the word “secularism,” its etymology and its semantics, which I started addressing in the second article of this series.

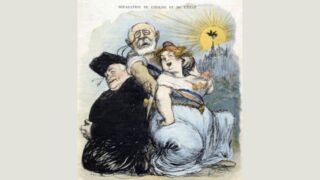

What all my interlocutors in Bangladesh, believers (most of them) or not, strongly advocated (when they feel it threatened) and supported (when they praised the current situation) for the country was the formal separation of the state from religion, preventing the latter from influencing the first, or even becoming its hostage. At first glance, it resembles the cultural climate of those Western countries—in this series, I previously discussed France—where the reason for that separation is the state’s open hostility, masked as it may be, to religions. In Bangladesh, however, it is rather the opposite.

Bangladesh is a religious country. The huge majority of Bangladeshi citizens are believers and Muslims. Those of them who advocate separation between state and religion want to avoid that one faith prevaricates on others. The same is true for some foreign observers I talked to there, who insisted that a confessional state that legally entrenches one religion at the expenses of others is to be avoided for the sake of minorities. This is the ground where both believing and non-believing observers, Bangladeshi or not, can easily agree and work together.

In sum, what they criticize is “confessionalism.” Yet, using the argument of secularism can be highly dangerous. The risk is quite evident for believers, who may be easily and paradoxically be mistaken for advocates of irreligion. But it is dangerous even for agnostics, who may be wrongly perceived as advancing an ideological agenda, while they are only defending the right of everyone, especially the members of minorities (which are weaker by definition), to religious liberty.

The conclusions I drew on the Bangladeshi ground is that, the etymology and true meaning of the word “secular” notwithstanding, “secularism” can hardly be a banner for those who want to genuinely defend religious liberty, particularly if they are believers. It is also evident that the word itself is used in different ways.

For non-believers, it would be contradictory to advocate a free right to believe on the basis of a “secularization” of faith. For believers, secularism as “non-confessionalism” may be a working compromise—or the object of a temporary “suspension of belief,” to reverse the famous expression used by English poet, critic, and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) in his 1817 “Biographia Literaria” to describe the semblance of truth that an author puts into a fictional story to make it credible, asking readers for a momentary “suspension of disbelief.” But in both cases, the concept of secularism would not work.

Bangladesh is a bizarre country. It could be easily described as an oxymoron: the chimeric result of two opposite concepts, which may produce beautiful poetic effects as a trope in Hermetic poetry but in practical life forces to coexist things that in reality cannot be put together. The point here is its Constitution.

The Bangladeshi government adopted its current Constitution on December 16, 1972, on the first anniversary of the country’s victory in the Liberation War (March–December 1971), which coincided with a genocide perpetrated by Pakistan, as also “Bitter Winter” illustrated and a recent fact-finding mission ascertained. The Constitution has been amended 17 times up to 2018. As its Preamble says, and Article 8 repeats, four are the pillars of the Bangladeshi state.

One is socialism, chiefly in economy, as per Article 10. While one may find hard to defend democracy, human rights, religious liberty, and equal opportunity for all on socialist stands, given the bad and bloody precedents of Marxist-Leninist “real socialism” regimes, from Bangladesh I brought back the understanding of that word that several Bangladeshis bright-mindedly give: “social care,” with not an inch of courtship to “real socialism” (which of course doesn’t imply that one needs to uncritically accept that semantization, nor that real socialists do not exist in that country).

Nationalism is another pillar, as per Article 9, and this is quite tricky. While one should be always careful to put the words “nationalism” and “socialism” side by side, separated only by a thin comma, especially in a country which suffered a genocide, the “nationalism” mentioned in the law of the Bangladeshi land means identity, language, and culture. The tricky part here is that it may indicate both the legitimate patriotism of the Bangla nation, or a version of the dangerous “nationalist” ideology of the nation-state described in the second article of this series.

Democracy and secularism are the most intriguing Bangladeshi constitutional pillars. Article 11 describes Bangladesh as “a democracy in which fundamental human rights and freedoms and respect for the dignity and worth of the human person shall be guaranteed.” Here it is licit to suppose that secularism, as per Article 12, is the way Bangladeshi institutions devise to achieve that goal. In fact, the Constitution describes secularism as the “elimination of (a) communalism in all its forms; (b) the granting by the State of political status in favour of any religion; (c) the abuse of religion for political purposes; (d) any discrimination against, or persecution of, persons practicing a particular religion.”

But while clause (a) sounds suspiciously similar to the “separatism” that France denounces to curtail religious freedom, clause (b) is contradicted by Article 2A that makes Islam “the state religion of the Republic,” to the point that the Constitution itself begins with the invocation “In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. In the name of the Creator, the Merciful,” all written in Arabic, the language of Allah’s revelation in the Quran. Of course, this is the result of subsequent additions, yet they contradictorily remain together in the same fundamental law of the land.

As to clauses (c) and (d) of Article 2A, signs of concern are multiplying in the country. It would of course be very naïve and unjust to automatically attribute to the Bangladeshi institutions the bloody actions and hate speech of some individuals and private groups that act independently against minorities or persecuted groups, and blame the Constitution for them. However, it is equally obvious that the government and the police should do all that is in their legal power to prevent and punish any wrongdoing coming from religion-inspired groups and individuals—especially if these groups and individuals belong to “the state religion of the Republic,” no matter how misinterpreted and twisted by extremists that can be.

Many in fact doubt that the government and the police always do all that is in their power to restrain the intolerance that is tempting some sectors of Bangladeshi society. They in fact wonder to which extent a government operating under a Constitution that acknowledges both Bangladesh as secular state and Islam as its state religion is willing and/or has the force to confront groups and individuals preaching and practicing intolerance in the name of the religion of the state.

The government’s, to be sure, isn’t an enviable position. Its intervention against radical Islamists may risk alienating also, out of misunderstanding or suspicion, many Muslims who have nothing to do with extremists. At the same time, the government should remain outside of theological disputes: but, being Bangladesh a secular state with a state religion, this may be hard and ambiguous in both directions.

The forthcoming elections complicate the picture. In January 2024, Bangladeshi citizens will vote to elect the 12th Jatiya Sangsad, or “House of the Nation,” i.e., the 5-years-mandate parliament. Upon the result, the President of Bangladesh will, per the Constitution, appoint the prime minister.

The Bangladesh Awami League (AL) leads the coalition governing the country since December 2018, expressing the Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina Wazed, daughter of “the father of the nation,” Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (1920–1975). A center or center-left party, it originated in the late 1940s as a Muslim national(istic) party offering Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) an alternative to the centralizing Muslim parties of Pakistan. It played a central role in the fight for Bangladeshi independence under the leadership of Rahman. The major party of the opposition is the center-right Jatiya Party, but the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), led by former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, is also able to play a significant role, even if it presently has a small parliamentary representation.

While all Bangladeshi political parties are officially secular, none of them wants to lose the Islamic votes that represent a significant portion of the electorate. And Islamist votes count too. This is why, as observers lament, both right and left act very carefully towards radical Muslims, sometimes even ambiguously, independently from their official statements. For this reason, many fear that the image of Bangladesh as a tolerant country, proudly upheld in official speeches, is vacillating.

Or it is the bizarre image of a secular state with a state religion that vacillates. Bangladeshi communities and patriots are seriously worried, seeing foreign powers, namely Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China, fanning the flames. But if confessional extremism is a disease that must be stopped before it is too late, secularism is not the medicine—even when it means only “non-confessionalism.” The fourth and last article in this series will discuss this point.