The former Dutch MP led a fact-finding team to the Asian country. His conclusion: no more doubts are possible.

by Marco Respinti

Can a massacre that happened in 1971, with the world watching, still go unnoticed by many? This is what Henricus “Harry” van Bommel and others tried to ascertain in Bangladesh.

Van Bommel is a Dutch politician and human rights activist. Born in 1962, he holds a Master Degree in Political Science and a Bachelor Degree in Education. He was a member of the House of Representatives in the Dutch Parliament from 1998 to 2017. Before entering Parliament, Van Bommel was a member of the Amsterdam City Council and a language teacher. In Parliament, he focused on foreign policy and relationships with the European Union. He was a member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and participated in several election observation missions. He is actively involved in the work of the European Bangladesh Forum (EBF), the Uyghur Support Group Netherlands, and the International Human Rights Committee. With others, he contributed an article in “Bitter Winter” on the need for the international recognition of the genocide perpetrated in Bangladesh by the Pakistani Armed Forces in 1971.

What about your recent mission to Bangladesh?

I went to Bangladesh as the leader of a fact-finding team which stayed there on May 20‒26, 2023, mainly to find personally out what really happened during the 1971 Liberation War, as well as the extent of atrocities and crimes committed by Pakistan against the Bengalis. Our visit was organized by the EBF, a diaspora organization, in collaboration with its partner organizations in Bangladesh: Amra Ekattor, which upholds the values of the Liberation War, and Projonmo ’71, which reunites the children of the martyrs of the war. The fact-finding team included Dutch university lecturer Anthonie Holslag, British political analyst Chris Blackburn, and two Bengali human rights activists, Bikash Chowdhury Barua and Ansar Ahmed Ullah.

How did your team organize its work on the ground?

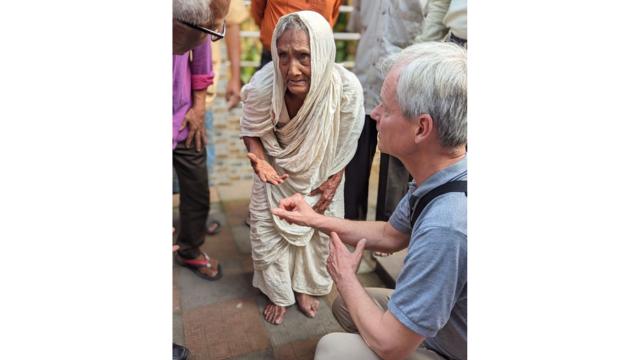

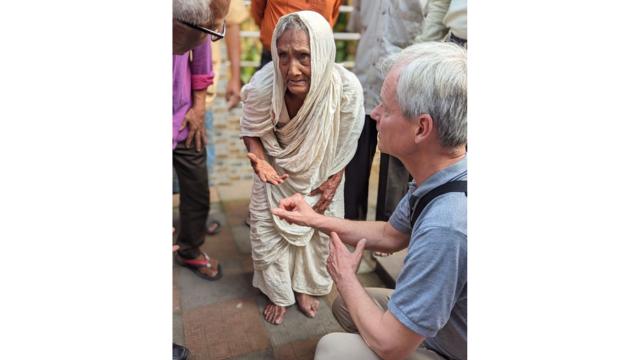

The local organizations, working with EBF, have a good network in Bangladesh, with strong manpower. The preparation of our mission was perfect. They also organized meetings with victims and their families, visits in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, to the International Crimes Tribunals (ICT), the Centre for Genocide Studies at the University of Dhaka, and the Liberation War Museum (LWM), as well as field trips to the killing fields of 1971. We could talk to researchers working on the topic, read testimonials in the ICT archives, and see spots both in Dhaka and Chittagong, the second largest city of the country, where the major genocidal acts took place. By far, the most impressive encounter I had was with a 90-years old lady, who witnessed the killings in her home village, Jaga at Raozan, Chittagong District. In one incident, she told us, the Pakistani soldiers killed 43 people, including men, women, girls, and young babies. I could see the grief in her eyes, even now, fifty years later.

What did your team find and conclude?

Talking to survivors, visiting the killing sites, and reading documents in ICT we came to the conclusion that there is enough physical evidence in Bangladesh to support the scientific consensus that 1971’s was a genocide. Our meetings with scholars at the University of Dhaka and the LWM reinforce this conclusion as well. We will now take our findings to Parliaments in Europe and across the world. We will publish an official report to accompany a petition addressed to the Dutch, the British, and the European Parliaments to seek promotion for the international recognition of the genocide. This will take place right after the summer. We will organize conferences in the Netherlands and possibly in other countries in early 2024. For the general public, we will publish a booklet with stories told us by the families of victims. We are also finalizing a documentary film. The idea is to get political and public awareness of the Bangladesh genocide, to be then followed by its formal recognition. The Bengali diaspora will be actively involved in this campaign.

Yet many still ignore that tragedy…

The scientific evidence is widely available. Many documents refer to the atrocities as genocide: diplomatic messages, articles in internationally renowned newspapers, TV news footage, and many other sources. Despite all this, the international community remained silent, which is one of the dirtiest crimes. Geo-political games are also involved. The US took the side of Pakistan, and so did China and Saudi Arabia. When the political power in Bangladesh shifted, four years after its independence, with the brutal killing of the father of the nation, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (1920–1975), during a military coup, the new government stopped all initiatives to move forward the campaign for international recognition. The good thing is that today a number of international organizations are mobilizing. A bipartisan resolution calling for the recognition was tabled in the US House of Representatives by two Congressmen, Steve Chabot, Republican, and Rohit “Ro” Khanna, Democratic. Non-governmental organizations, working on prevention and accountability, such as the Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention, Genocide Watch and the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience recognized the 1971 genocide in separate statements in 2021 and 2022. And most recently the massacre was acknowledged as genocide also by the International Association of Genocide Scholars. All this calls world bodies to action. No, it is not an obscure topic.

The human cost of 1971 is put forth by a recent documentary by Global Human Rights Defence. What did your team find as to numbers?

There is no doubt that many girls and women were violated, people killed, houses, temples and churches burnt to ashes, and that people had to flee to neighboring India for refuge. As per the Bangladesh government statistics, there were about three million people killed, more than 200,000 girls and women violated, and over one million people who took shelter in refugee camps all over Bangladesh, where, according to some reports, around one million were also killed. These deaths were caused by the atrocities committed by the Pakistani Armed Forces. The numbers were confirmed to our delegation by the Center for the Study of Genocide and Justice, established by the LWM, and other scholarly institutions. I have no reason to doubt these figures.

Does the present Bangladeshi government pay enough homage to the victims of the genocide?

Today the government in Dhaka, which is known as pro-liberation and secular, has taken a number of initiatives and programs to upload the spirit of 1971 Independence War. It set up a Ministry of Liberation War Affairs and made a list of the freedom fighters. The sad aspect is that it seems that many fake freedom fighters have been included in the list to enjoy the financial and other benefits provided by the government, while many real freedom fighters are neglected. Anyway, the government also arranged a monthly allowance for freedom fighters as well as quotas for their children and family members in educational institutions and jobs. Both victims and freedom fighters have been granted national gallantries, including financial support. A number of foreign nationals were given the title “Friend of Bangladesh” and accorded reception in the country. In this regard, I would like to mention that one of our team members, Chris Blackburn, was also awarded as “Friend of Bangladesh” by the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina Wazed, who is the eldest daughter of the assassinated father of the nation. A Dutch-Australian citizen, William A.S. Ouderland (1917–2001) was a commando officer and the recipient of the Bir Protik, Bangladesh’s 4th highest gallantry award, from the Dhaka government, in recognition of the support he gave to the country during the Liberation War. In 1971, he was posted in Bangladesh and operated with the freedom fighters. Having said that, I have doubts that this government is doing enough for the international recognition of the 1971 genocide. Although it is sincere and committed to this issue, it is not active enough to raise the issue globally. When our team met the Dutch ambassador in Dhaka, Anne van Leeuwen, he expressed his surprise saying that no one from the Bangladeshi government has ever approached him either to discuss the 1971 genocide or to know the Dutch government’s stand on the issue. The Bangladeshi government should instruct its foreign missions to be more active in this regard, especially now, as the issue of recognition is raised in the US and the UK and will be in the Netherlands and other EU member-states.

There are signs of growing religious fanaticism and intolerance in Bangladesh. Is there the risk that the country may slip into another bloody phase of its history?

I am optimist. As said earlier, the present government claims to be secular, although sometimes attacks take unfortunately place in different parts of the country. Some Islamic groups do create problems and incite violence in the country in the name of religion. In recent past, Islamic violent extremists butchered a sizeable number of foreign nationals in the capital Dhaka. The government was able to neutralize those violent people, but fundamentalist groups always pose threats. Some are still active, although not as they were a couple of years ago. Still, the government must remain vigilant. Otherwise the situation may take a serious turn. Fundamentalists are against the spirit of the 1971 Liberation War and want to turn Bangladesh into a country run by Shari’a.

What is next for people caring for the 1971 genocide?

It will take an international effort to achieve its formal recognition. Today, while the facts are known by scholars, institutions and many politicians, the world community knows little about it. The Bangladeshi diasporas must be more aware and more active, and they should operate to reach out to the mainstream population, seek their support and the support of European politicians as well. Pressure has to be made both at national and international level, and all has to be then taken to the United Nations. I have committed myself to help EBF in reaching this goal. I in fact strongly demand that the 1971 genocide in Bangladesh is recognized to give justice to its victims and bring perpetrators to judgment. I call upon the United Nations General Assembly and other international entities to formally recognize that massacre—one of the darkest yet most overlooked chapters in human history. Through confronting the past with sincerity and truth, and rising above narrow political interests, we can acknowledge our shared humanity and join hands for a safer, peaceful world.